Ilya Glazunov, who died 9 July, was one of Russia’s top two regime artists, sharing this pinnacle with Tsurab Tsereteli, creator of the vast Peter the Great monument in the centre of Moscow.

Like Tsereteli, he realised that Russians had tired of the relentlessly optimistic, forward-looking tropes of Soviet Realism and tapped into the romantic nationalism of the people and their rulers.

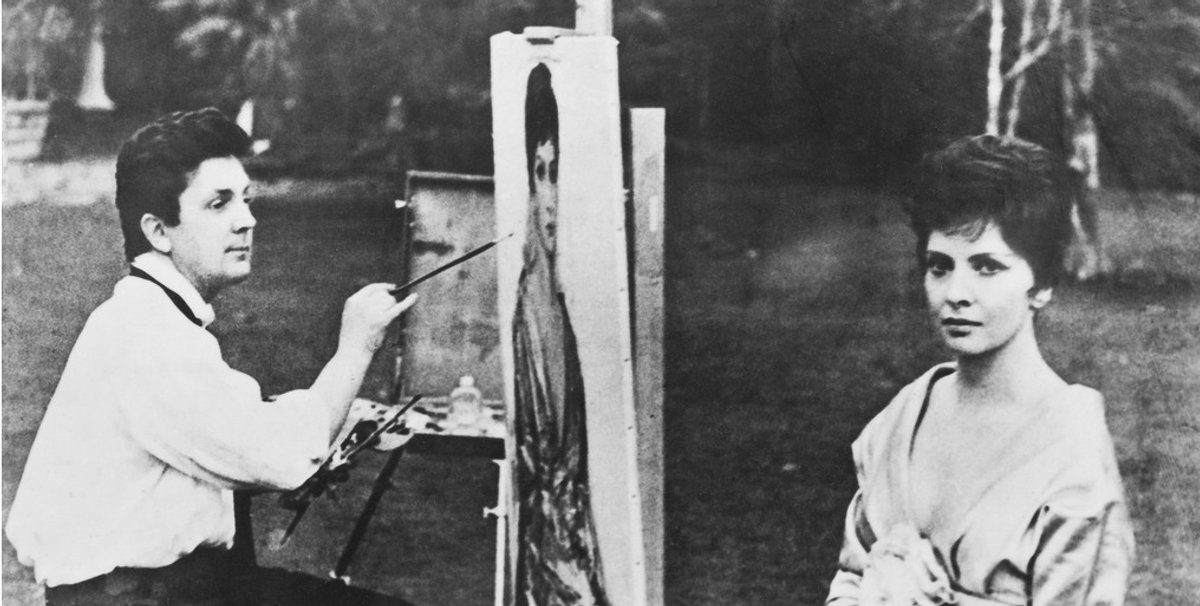

He was born in Leningrad in 1930, studied at the Repin Academic Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture and married Nina Vinogradova-Benois, a descendant of the stage designer Alexandre Benois and cousin of the English actor Peter Ustinov, and herself a talented costume designer.

I met them both early in 1986. It was at a dinner in his very large—for Moscow—duplex. Downstairs was cool Empire-style, but upstairs it was all Mother Russia: a pseudo-religious, dimly lit, bit of theatre, with icons covering the walls, incense and liturgical music. I was there to organise an exhibition in the series of exchanges with the Hermitage that Hans-Heinrich Thyssen had set up with the Soviet government. Baron Thyssen was the guest of honour, accompanied by Simon de Pury, then his curator. The atmosphere was oppressive, the lavish meal interminable, while the ecclesiastical mood kept being disturbed by the tape running out. Glazunov’s wife, white-faced and totally silent, waited on us like a servant. I was not surprised when I heard, a few months later, that she had committed suicide by throwing herself out of a window.

The artist presented the baron with a pearl-studded icon and then asked to see a picture of Thyssen’s new wife, Tita. The baron obliged and Glazunov stared at it enraptured: “This is the face I have dreamt of painting all my life”, he said. Used to sycophancy, the baron smiled slightly and said nothing, but Glazunov got his commission and painted both the baron and baroness. I wondered whether this was part of the deal with the Soviet government. For Glazunov managed to tread the fine line of apparently being a rebel (a role that guaranteed him a brief approval in the west) while rising inexorably in the favour of the ruling caste. His diploma painting, of Soviet soldiers in retreat, was rejected and then burnt after he showed it in 1964, but Khrushchev liked his art and he began a charmed existence.

In 1963, he was allowed to go to Italy to paint Gina Lollobrigida, which launched his career as portraitist to the famous. When the USSR opened diplomatic relations with India in 1973, he was sent to paint Mrs Ghandi. He went on to paint the Italian president, Sandro Pertini, Pope Paul VI, Fidel Castro, King Juan Carlos and many others.

His portraits are conventional exercises in flattery, but his vast history paintings, three by six metres, were excitingly new for the Soviet public. They should be read in the light of his politics. In the 1970s he was a leading light of the historical association Vityaz (Knight), the People’s National-Patriotic Orthodox Christian Movement that became Pamyat (Memory), the ultra-nationalist organisation that exalted the Church and attributed most of the ills of Russian society to a Zionist plot. Glazunov’s politics did not change; there is a recent photograph on his website of him arm in arm with Jean-Marie Le Pen.

In 1976, he executed the work that made his name, The Mystery of the 20th Century, full of figures exemplifying the violent clashes of modern times: the last tsar with Lenin, who deposed him; Hitler, persecutor of the Jews, with Albert Einstein, the Jewish genius; an atomic explosion that could end time with the timeless Sphynx. Jesus Christ floats above the throng, which includes the dissident writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn. This detail got him into trouble with the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party, but protection from on high meant that he got sent, not to a gulag, but to paint the builders of the Baikal-Amur railway in Siberia. It gained him brief fame in the western media, which saw it as an example of courageous dissidence, and it circulated within the USSR in samizdat form, until the 1980s and perestroika, when it was finally exhibited publicly.

As the Socialist dream became more and more a mirage, the historical past denounced since the 1917 Revolution began to seem more alluring. Crammed with figures, sometimes taken from famous existing images, his paintings introduced personalities from pre-revolutionary days: the last tsar and his family, Peter the Great, Empress Catherine the Great, 18th- and 19th century nobles and intellectuals, all mixed up with Lenin, Stalin, and the Orthodox saints, painted like icons with golden halos.

There was plenty for the viewer to spot and identify, and he would sneak in faintly daring surprises, like the small punk with a green Mohican in the corner of The Great Experiment (1990), a painting about Russian communism.

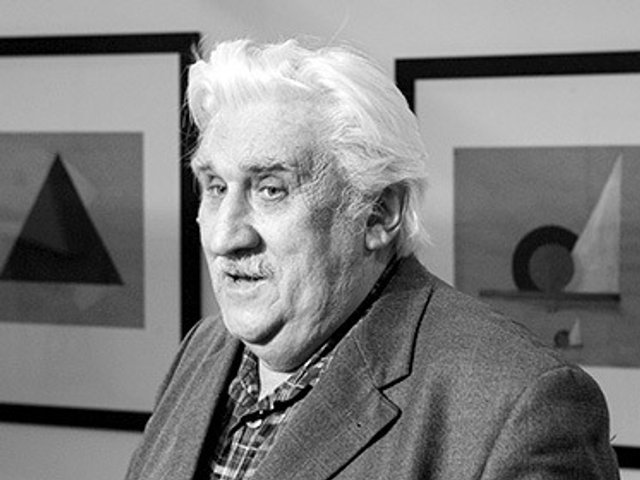

Never seriously in trouble, Glazunov had his first major show in the prestigious Manege next to the Kremlin in 1978. The queues stretched around the block, as they did for all his subsequent monographic shows right up to 2011. Presidents Yeltsin and Putin, and the powerful Mayor Luzhkov of Moscow, all admired him and he was able to set up a museum of his own works, the All Russian Academy of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture to teach his style of painting.

The Orthodox Church, which was reasserting its ancient role of influence within the Kremlin, loved him and he it. He painted its patriarchs, saints, monasteries and key historic moments. He campaigned successfully for the rebuilding in the late 1990s of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour on its original site, which the Soviets had turned into a swimming pool.

In his silk shimmer suits and sharp blazers, with his silver quiff and fleshy face, he looked nothing like an artist, more like a member of the luxury-obsessed oligarch class that arose in the 1990s. A poll conducted in the 1990s by the Russian Public Opinion Research Centre, voted him the most outstanding Russian artist of the 20th century, while Unesco awarded him the Gold Medal of Picasso for his contribution to culture and art. In 2012, Putin made him a personal representative and honours were heaped upon him, but the international contemporary art world has had no room for him. In the first and only Sotheby’s sale in Moscow, organised by Simon de Pury with the genuinely dissident artists of the 1970s and 80s, four works by Glazunov were included, rather under duress. Not one of them sold.