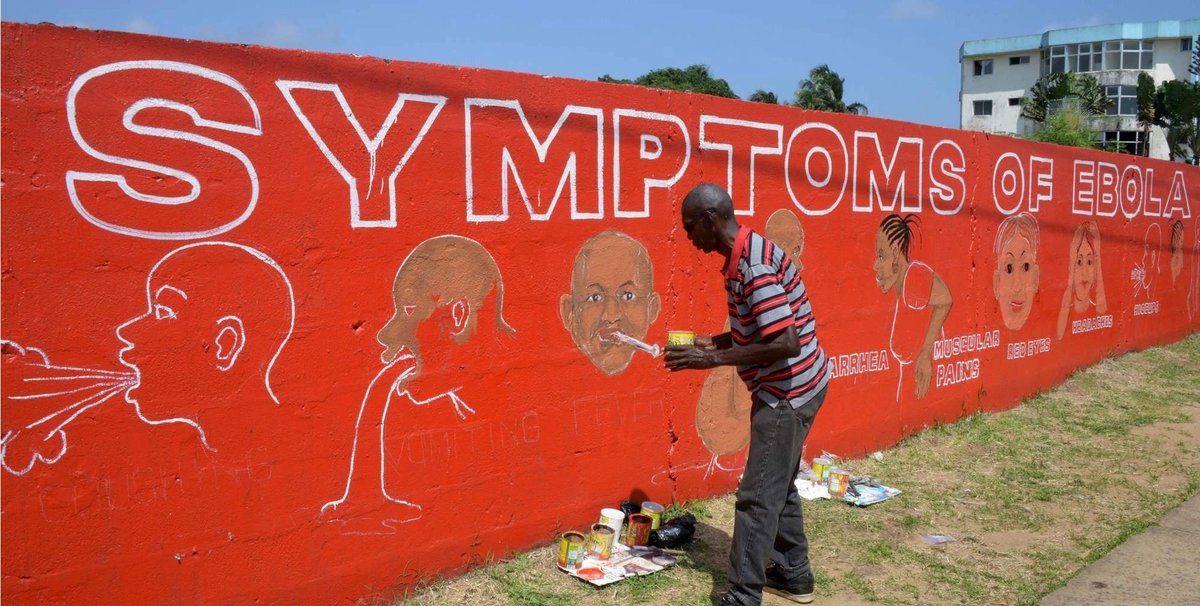

Can graphic design save your life? The curators of an exhibition posing that question at London’s Wellcome Collection think so, and have martialed around 200 examples ranging from designs for the outside of ambulances, hospital interiors, hard-hitting posters, cigarette packaging and images of street art aimed at alerting and informing the public about an epidemic. Examples in the exhibition (7 September-14 January 2018) range from a Second World War anti-malaria poster designed by Abram Games to the artist Stephen Doe painting an educational mural about Ebola in Liberia in 2014.

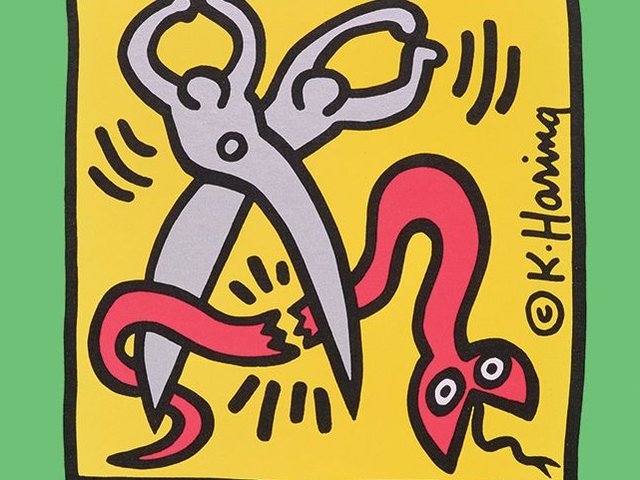

Rebecca Wright, who has co-organised the show with graphic designer Lucienne Roberts, says that exhibits in a section about contagion are especially dramatic. An Italian “plague notice” from 1681 “uses bold typography to give authority in time of panic,” she says, adding that it is a beautiful object. Graphic design responding to the early spread of HIV/Aids is included, such the historic and controversial, “Don’t Die of Ignorance” campaign launched by the British government in 1986. “It was the first time every household in the UK received a health leaflet,” Wright says. The campaign, which was led by TV advertisements, one featuring a tombstone and another with an iceberg with the word “AIDS” below its surface, had a simple and apocalyptic message. “It has been called counter-productive but you get a sense of the urgency and complexity of the communication campaign,” she says.

An “interactive” poster installation from Brazil is especially ingenious. Created in response to the Zika virus, it uses smart technology: mosquitoes are attracted to the surface of the poster because it is sprayed with a scent based on human sweat. The substance is fatal to the insects. “It raises awareness in a clever and humorous way,” she says.

The show will include work by the greats of wartime and post-war graphic design, including F.H.K. Henrion, who was born in Germany and took its Bauhaus-inspired, Modernist design to Britain in the late 1930s. Wright points to a poster by Henrion aimed at servicemen during the Second World War about the dangers of catching venereal diseases. Like Games’s work, Henrion’s shows “how powerful minimal means can be,” and the sophistication of their design. Other works are by Margaret Calvert, Fritz Kahn, Dick Bruna and Ken Garland as well as companies such as Pentagram, among others.

The curators believe that graphic design has and does save lives, so why the question mark in the exhibition’s title? “We wanted to be provocative and to let visitors make up their own minds,” Wright says.

Wellcome Collection in London is part of the charitable foundation originally created by the pharmaceutical giant Burroughs Wellcome & Co. US-born, British-based Henry Wellcome was an obsessive collector of all things related to medical history. The exhibition draws on his collection and the company’s archive.