A Holocaust-related lawsuit seeking a Camille Pissarro painting from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation in Madrid was revived yesterday by a federal appeals court in California. The previous dismissal in 2015 by a federal judge in Los Angeles was incorrect, the Ninth Circuit court of appeals said, because the plaintiffs should be permitted to prove the museum knew the painting had been stolen.

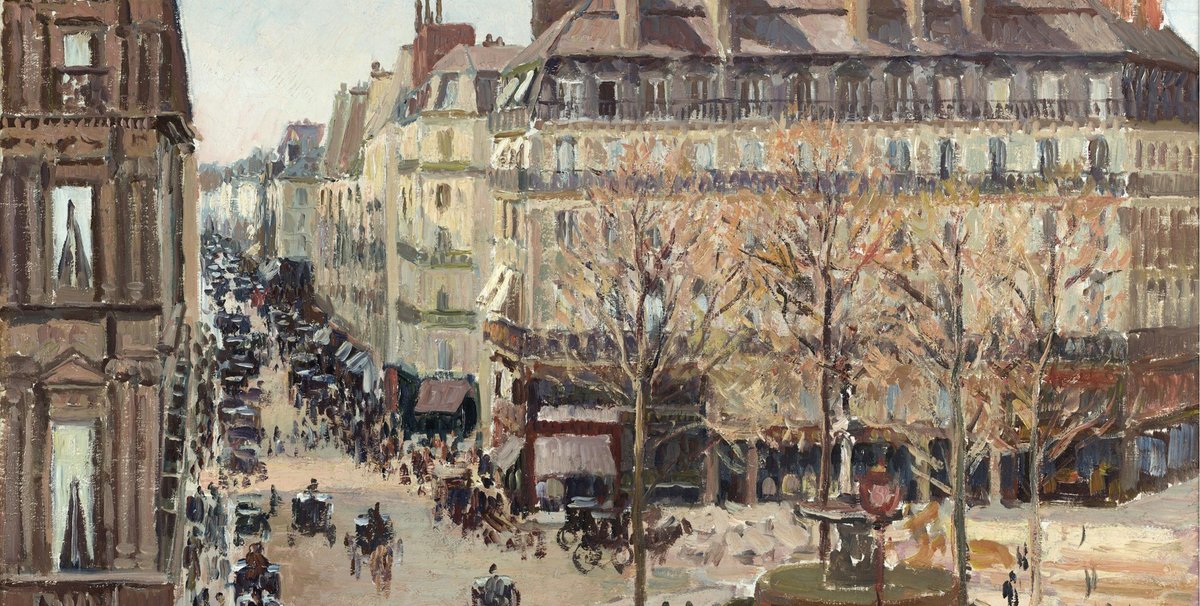

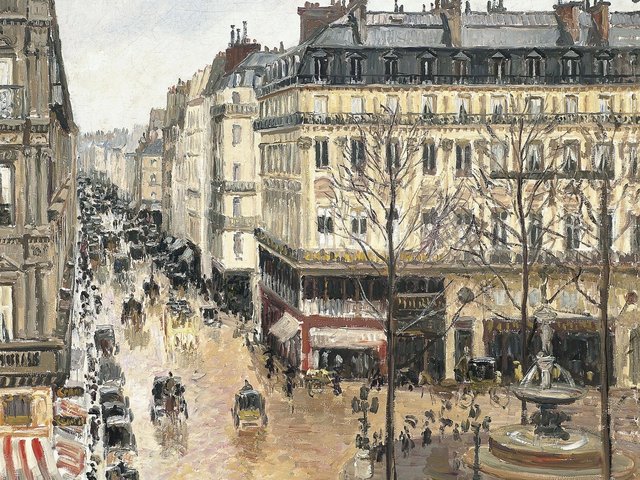

The reversal opens up a new path for a long-standing suits. The plaintiffs are David and Ava Cassirer, great-grandchildren of Lilly Cassirer Neubauer. In 1939 Neubauer, a German Jew, was forced to sell the painting of a Paris street scene, Rue Saint-Honoré, dans l'après-midi. Effet de pluie (1897), for $360 in order to flee Germany.

The painting was allegedly sold at a Nazi-government auction and then changed hands several times before it was purchased in 1976 by Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza. In 1993 the baron sold it and his other art to Spain, which refurbished the Villahermosa Palace in Madrid as a museum to exhibit it to the public. Neither the baron nor the museum had a hand in the 1939 sale.

The lower court determined the 1939 “sale” was a forcible taking, so the painting was stolen property. But it ruled that the museum was its rightful owner and dismissed the suit.

The appellate court disagreed. Applying Spanish law—because the painting was located there and the Spanish government had purchased the baron’s collection—it said the Thyssen-Bornemisza could be an accomplice to the theft if it knew the painting was stolen when it acquired it in 1993. Since on their appeal the Cassirers offered evidence the museum may indeed have known, the court said they should have an opportunity to prove it.

In a statement to The Art Newspaper, the museum’s lawyer, Thaddeus Stauber, of Nixon Peabody, said that because his client had acquired the Pissarro “in good faith in 1993—where it has ever since been on display to the public—we remain confident that the Foundation’s ownership of the painting will once again be confirmed”.

Particularly telling for the appellate court were the “red flags” cited by noted Holocaust historian Jonathan Petropoulos. According to Petropoulos, Pissarro paintings were “immediately suspect” because they were favored by Jewish collectors and often looted by the Nazis. In addition, the painting’s provenance was incomplete, and public documents available when the museum purchased it identified the owner as the Cassirers’ great-grandmother.

The court noted the baron had paid only $275,000 for the work, allegedly about half its value at the time. The museum’s “knowledge of the below-market price . . . may also suggest [it] knew the Painting was stolen”, the court wrote.

The decision also includes the tantalizing suggestion that other works in the Thyssen-Bornemisza may also be stolen. The museum paid $338m for the baron’s collection when, the Cassirers allege, its estimated value was three to six times that. The court said that although the museum “offers a number of innocent explanations for this below-market price, this fact may indicate that [it] knew the [Pissarro] and other works in the collection were stolen”.

The Cassirer family’s battle with the museum started in 2001, when they filed a petition in Spain to recover the Pissarro. When that petition was denied in 2005, they filed their lawsuit in California, which has now gone to the appellate court three times. Some of the skirmishes concerned whether their suit was barred by the statute of limitations. Monday’s decision appears to have put that issue to rest. The court said that under the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery (HEAR) Act of 2016, the lawsuit was timely because it had been filed within six years of the Cassirers’ discovery the painting was at the Thyssen-Bornemisza.

The Cassirers’ lawyer, Steve Zack, of Boies Schiller Flexner, described the “many years of agony” his clients have undergone during their 16-year fight for the Nazi-looted painting. “It’s a significant scar on the psyche,” he said.