The seemingly unstoppable rise of post-war Japanese art has been one of the major art- market success stories of the past ten years. Despite a history of engagement with Europe and the international art scene, the Gutai Art Association—founded in Osaka in 1954 by Jiro Yoshihara (1905-72)—had, until relatively recently, created few ripples in the art market. Pioneers in the combination of performance and plastic arts, the Gutai group presaged many of the developments that would come to define post-war American and European practice. Yet on his death in 2008, an obituary in the Independent newspaper for the group’s most famous proponent, Kazuo Shiraga, deemed him “largely forgotten”, and as recently as the early 2000s, works by the artist were selling for five figures at auction.

This began to change in 2005, when the Belgian collector and dealer Axel Vervoordt quietly began to acquire Gutai works. In 2008, just after Shiraga’s death, the artist’s prices broke the million-dollar mark at auction when Tenkosei Kaosho (Ne En 1924) (1962) sold for €726,650 (around $1.15m) at Christie’s Paris.

A spate of critically acclaimed museum shows, including Gutai: Splendid Playground at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2013 and Between Action and the Unknown: the Art of Kazuo Shiraga and Sadamasa Motonaga, at the Dallas Museum of Art in 2015, brought the movement greater public renown.

Prices followed in lockstep. In June 2014, a 1969 painting by Shiraga, Gekidou Suru Aka, sold for €3.9m ($5.3m) at Sotheby’s Paris, a record for the artist that still stands. In October 2015, Christie’s introduced a new sale series in London, Asobi: Japanese and Korean Modern & Contemporary Art. The inaugural auction, held on the heels of the house’s seasonal sales of contemporary art, made a total of £2,285,875 on 52 lots. Gutai had gone from marginal to a rock-solid bet.

What has followed has been a perhaps-inevitable softening of the market. The 2016 iteration of the Asobi sale managed less than three-quarters as much as the previous year, making £1,654,250. This year, in Bonhams’ March sale of post-war and contemporary art in London, Séi, a work by Shiraga from 1991, failed to meet its estimate of £500,000 to £700,000, prompting observers to speculate that his market has peaked. Grégoire Billault, the head of contemporary art at Sotheby’s New York, has had a better view than most of Shiraga’s rise, having been based in Paris when prices first began to skyrocket. Europeans have a longer relationship with the movement, he explains. “Shiraga was sold by Galerie Stadler in Paris in the 1960s, so there was a lot of work available. That’s how the market was built relatively quickly,” he says.

“A big price will always drive the market,” Billault says, nodding to dedicated collectors such as Howard Rachofsky, the Dallas-based former hedge fund manager who amassed around 100 pieces by Gutai artists during the boom. But high prices can also act as a destabilising factor, leading to a glut of available material. “When people can buy for $200,000 and sell for $2m, it’s irresistible for some of them,” Billault says. “I think it just needs a bit of time. It’s a question of needing a bit of maturity.”

Dominique Lévy, of Lévy Gorvy gallery, who entered the Gutai market around ten years ago, says, “What happened with Shiraga is unfortunate. He went from complete unknown to complete fever, and now to a very strange moment of calm.” She mounted a show at her London gallery in February and reports that two works sold “at what we consider market price—which is a bit less than it was a year or two ago… right now [the market is in] a bit of a quiet moment, but it doesn’t call into question the quality of the artist.”

Not everyone is ready to accept the rise of Shiraga and Gutai as a market-led phenomenon. Reiko Tomii, a leading curator and historian of the Japanese avant-garde and the author of Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan, says: “There is a false assumption that markets and money talk loudest. The market is not an autonomous force, especially when it is so unfamiliar, as is the case with Gutai or [the] Mono-ha [group].”

Tomii uses the example of another recent Japanese success story. “When [Alexandra Munroe and I] reintroduced Yayoi Kusama to New York in 1989 at the Centre for International Contemporary Arts with the first ever retrospective devoted to her outside Japan, there was no market to speak of. We put the scholarship in place, and now she is a major, bona fide global market force.”

Tomii points to Munroe’s 1994 Guggenheim exhibition Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky as a defining event. “You have to understand: this was a major world moment for the study of post-war Japanese art,” she says. The show “opened the door to scholarship in the North American context. It made the post-war avant-garde a legitimate subject”.

More pointedly, she adds, “scholarship enabled the market to function. A gallery cannot just sell Gutai. If you put a Pollock or a Richter on the wall, you can sell them without explaining it. If you put a Shiraga on the wall ten years ago, you had to explain it to sell it. How do you explain it? You need specialist help.”

Fergus McCaffrey, a key figure in the creation of the market for post-war Japanese art, agrees. “I think that the basis of what has happened is grounded in scholarship,” he says. McCaffrey would know: he won a Japanese government grant to study art and aesthetics at Kyoto University for two years in the 1990s. In fact, his speciality in post-war Japan helped to launch his career as an art dealer after he left Gagosian Gallery in 2006. He put together a body of Shiraga’s work and showed it to Rachofsky and the art adviser Allan Schwartzman. He now represents the Shiraga estate.

Crucial in Gutai’s sudden boom, in McCaffrey’s view, was the fact that the group had essentially been ignored in the US since the 1950s. “Look at the market for Italian post-war work, or back to the late 1980s, when the German Neo-Expressionists started to make an impact in the US. There are these discrepancies in information and knowledge that pop up.”

These blind spots can prove lucrative when discovered by US tastemakers. “The essence of any art market is American collectors,” McCaffrey says. “If you don’t get American collectors involved, then you don’t have the interest [and] the volume or the scale to actually make a market.”

McCaffrey is exhibiting the work of Toshio Yoshida, one of the lesser known but most experimental members of the Gutai group, at his New York gallery (until 24 June). Auction buyers, too, are branching out. In the same Bonhams auction in which the higher-priced Shiraga bought in, a work by Shozo Shimamoto smashed its estimate of £80,000, achieving nearly £300,000. This was followed by the sale at Sotheby’s Hong Kong of a rare 1964 work by Shimamoto that doubled the artist’s previous record, selling for $2.6m. Further records were set for works by Atsuko Tanaka ($1.6m) and Sadamasa Motonaga ($1.3m).

At Art Basel in Basel this month, McCaffrey mounted a stand of works by Shiraga and the Italian postwar artist Carol Rama emphasising their visceral qualities. He sold Sekirai, a large, red-hued Shiraga, for $5m within the fair's opening hours. "For a 1997 painting, it's a new benchmark", he says.

As Gutai’s links to international groups such as Zero and even contemporary artists today become apparent, the group and its successors only seem more relevant. The inclusion of Takesada Matsutani’s monumental graphite, ink and shadow work, Venice Stream (2016-17), alongside contemporary artists such as Hajra Waheed in the exhibition Viva Arte Viva in this year’s Venice Biennale, shows that—more than 60 years after Yoshihara first called for artists “to do what has never been done before”—the spirit of the group is alive and well.

McCaffrey says: “You have to remember that there were 59 members of Gutai. Great works by great Gutai artists are going to continue to appreciate. I don’t think we are anywhere near the top of the high prices.”

Key works by Gutai artists 1. Kazuo Shiraga’s Gekidou Suru Aka (1969) is sold at Sotheby’s Paris in 2014

2. Kazuo Shiraga’s Chikisei Sesuisho (1960)

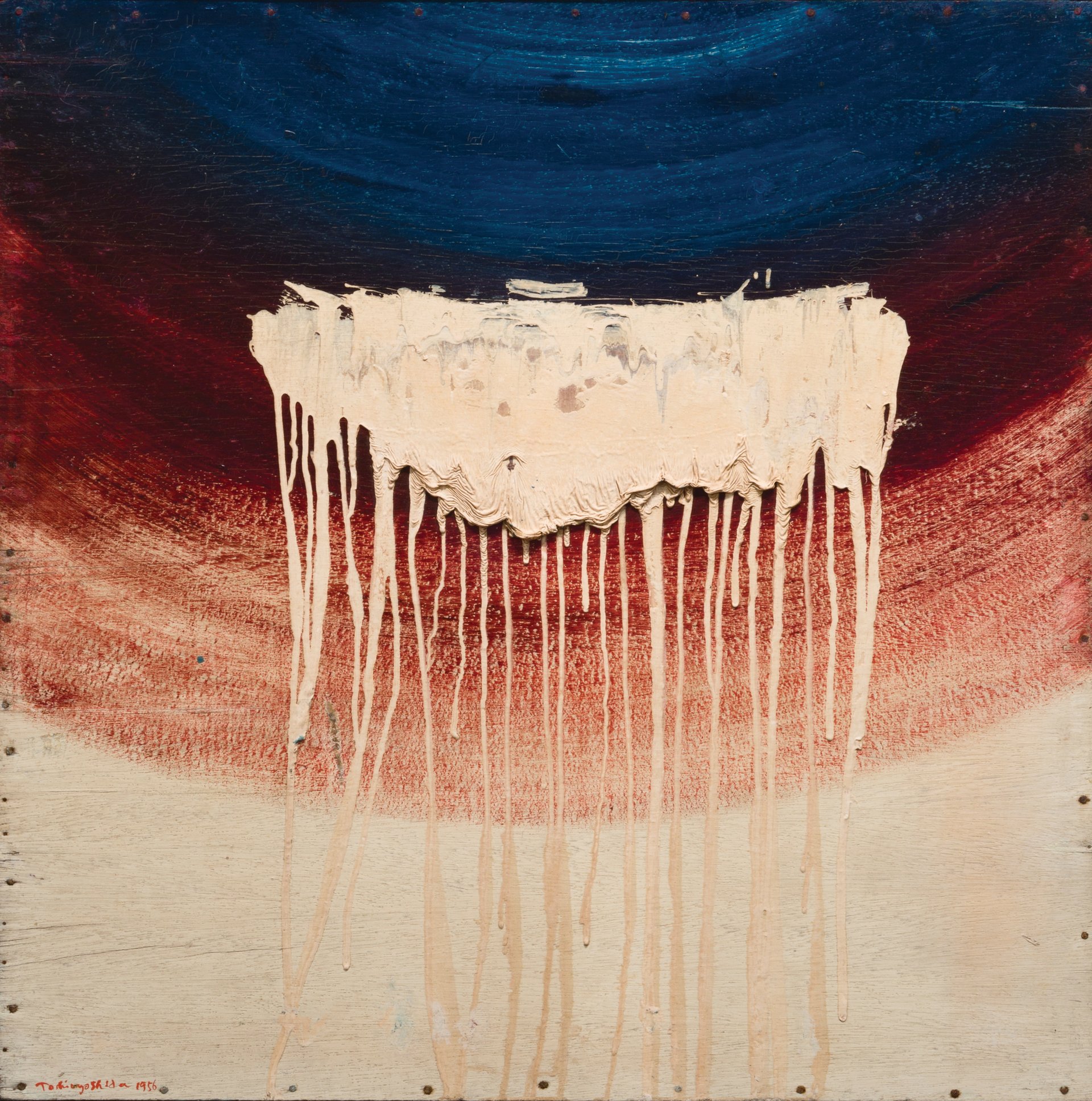

3. Tsuyoshi Maekawa’s Mannaka Tate no Blue (A18) (1964)

4. Toshio Yoshida’s Untitled (1956)

Time to buy 2005-07

Axel Vervoordt begins collecting; stages a Shiraga show at the Palazzo Fortuny in Venice

May 2008

Shiraga’s Tenkosei Kaosho (1962) makes €726,650 (around $1.2m) at Christie’s Paris

May 2009

Daniel Birnbaum devotes a room to Gutai at the Venice Biennale

March 2011

Ming Tiampo’s Gutai: Decentering Modernism, the first full overview in English, is published

May 2012

A record is set for Jiro Yoshihara when his painting Untitled (1966) sells at United Asian Auctioneers for HK$5.36m ($700,000)

February 2013

Gutai: Splendid Playground goes on view at New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

June 2014

Shiraga’s Gekidou Suru Aka (1969) makes €3.9m ($5.3m) at Sotheby’s Paris—a record for the artist that still stands

November 2014

Shiraga makes his debut in a flagship evening contemporary sale at Christie’s New York, when BB56 (1961) sells for $4.9m

February 2015

The gallerists Dominique Lévy and her former business partner Robert Mnuchin mount competing Shiraga shows in New York

October 2015

Yoshihara’s private collection makes $3.5m at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, achieving 100% sell-through and quadrupling the estimate