Jean Tinguely’s clanking, splashing fountain in front of the Theater Basel turns 40 this year and the city celebrated on Wednesday night with fireworks and a marching band. The artist’s radical, pioneering ideas live on at Art Basel, where this year a number of galleries are showing historic and cutting-edge mechanical and motorised art.

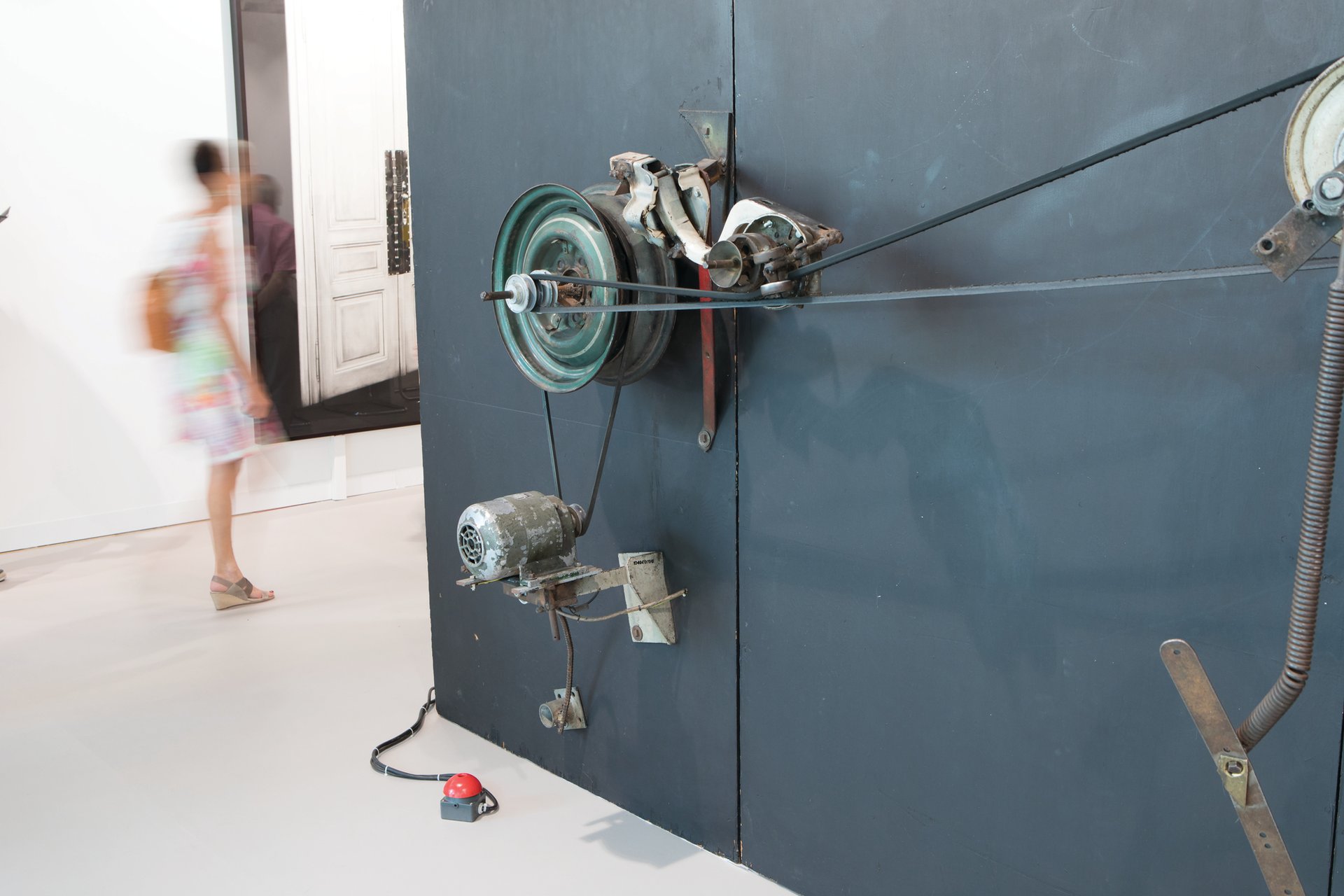

The Düsseldorf-based dealer Hans Mayer, one of Tinguely’s early supporters, has an impressive large-scale piece filling a wall of his stand. Although Attila (1963) may seem too big for most homes, Mayer says that he has seen works “three times this size” in private collections. “When a collector buys something like this, he knows exactly where he’s going to place it,” he says. And although the activated piece’s banging and clanging takes some visitors by surprise—Tinguely “liked to terrorise people”, Mayer gleefully admits—the noise can be reduced by putting rubber on the striking arms “so that it can run very quietly”, he says. Works by Tinguely can also be found on the stands of Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois and Von Bartha

Another early proponent of kinetic and Op Art is Paris’s Galerie Denise René, which has a number of spinning optical works from the 1960s by the Italian artists Gruppo MID that are manually activated with the twist of a dial. But the gallery also represents contemporary artists who are bringing mechanised art into the 21st century. The Venezuelan-born Elias Crespin’s Linea Copper (2016) is a delicate installation of metal rods and balls suspended on nylon thread that move in a computer-choreographed dance. “Once you install the piece, all you need is electricity and wifi; you can turn it on and off with an iPad,” says Galerie Denise René’s Debbie Frydman. In the case of a glitch, any troubleshooting can be done by the artist online with the help of an onsite technician. A more lo-fi example can be found in the work of Pe Lang, whose wall-boxes of sinuously rolling coloured tape, Color n°16 and n°17 (both 2017), run on just one tiny motor and an AAA battery.

Tinguely’s playful spirit is perhaps best embodied in the work of the Portuguese artist duo João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva, who prefer to work with “analogue technology”, says Johanne Tonger-Erk of Düsseldorf’s Sies + Höke. The gallery has a mini-exhibition of their kinetic sculptures at the fair, including Card throwing machine (2017), which whips playing cards across the stand; the undulating Rope/Snake (2017); and rigorously shaking Washing machine with leopard (2016). Compared with works that use 16mm film—and require a projector and the knowledge to run it—collectors should find Gusmão and Paiva’s pieces easy to accommodate. “You just have to be able to access the spring mechanism to replace the deck of cards when they run out. We have the tallest guy at the gallery go up there,” Tonger-Erk says.

Kinetic art’s appeal is strong for artists as well. The German artist Jorinde Voigt, who is known more for her drawings and sculptures, recently turned to motorised work as a way to create “a 3D depiction of one of the theme central to her work—movement in space,” says Rebeccah Blum of David Nolan gallery, which is showing the editioned piece Grammatik VII (2010). The series of propellers, inscribed with declensions of the verb to love using different subjects, can be set by collectors to move clockwise or counter, and fast or slow. This also plays to Voigt’s interest in creating “variations on a theme,” Blum says.

The easiest-to-operate mechanical work at the fair has to be Antonio Vega Macotela’s The Chisel and the Sinkhole (2016-17), a massive, music box-style instrument on the stand of the Mexican gallery Labor. A simple turn of the crank will get the work in motion and the only maintenance is a regular oiling of the gears. But the inevitable breakdown is a part of the art. “Right now, the artist sees it as just an instrument,” says the gallery’s Ana María Sánchez. One day, though, the work’s rusty hammers will corrode or its pipes will break and it will no longer be playable. “That’s when the tool will convert into a sculpture.”

Mechanical works to see at the fair

Jean Tinguely, Attila (1963) Galerie Hans Mayer

This classic Tinguely machine was originally created for a show at the legendary dealer Virginia Dwan’s gallery in Los Angeles. When Attila made its New York debut with two other sculptures and live actors in a play at the Jewish Museum, a theatre producer was heard to tell a friend: “The best performers were the machines.”

João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva, Card throwing machine (2017) Sies + Höke

A sneaky slit in this gallery wall spits out playing cards once every 60 seconds, scattering around other kinetic works by the Portuguese artist duo. “The cards point to the idea of trickery and fortune-telling,” says a spokeswoman for the gallery.

Thomas Baumann, Spacial Birds (in a conversation) (2016/17) Nicolas Krupp Contemporary Art

An electrified copper coil and magnets power these bobbing birds. Nicolas Krupp regularly brings kinetic works to fairs. “They capture people’s attention,” he says. The pair could be yours for €38,000.

Aimee Dawson