The Le Nain Mystery is a wholly accurate title for this exhibition at Louvre-Lens. There were three Le Nain brothers, all painters—Antoine (around 1600-48), Louis (around 1600-48) and Mathieu (around 1607-67)—about whom little is known. Their output amounts to around 75 paintings, of which 16 works are signed "Le Nain", tout court. A large part of their mystery is that it has been difficult, if not impossible, to assign works to individual hands.

It is known that the three moved to Paris in 1629, living in St-Germain-des-Prés, quickly built up a solid reputation and were famous by the 1640s. It seems likely that they painted for the newly rich bourgeoisie who were then becoming art collectors. There are a few known commissions, but Antoine and Louis were elected as founding members of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in March 1648. Both died two months later.

Mathieu, like many artists of the Early Modern Era, tried to raise himself socially, succeeding to the extent that Louis XIV made him a knight of the Order of St Michael—an honour restricted to those of noble birth. Mathieu claimed to be the Sieur de la Jumelle, a family farm near Laon. In 1663, however, he was struck off when his claim was found to be false. He was imprisoned in 1666 for continuing to wear the Order’s gold collar and died a year later.

Despite the want of documentary information, works by the Le Nains were held in high regard in their lifetimes. Disparaged towards the end of the century, their paintings came back into favour in the 18th (along with the taste for Dutch and Flemish art). At that time, first names were randomly assigned in sales catalogues, creating a confusion that persists. Their stars as 17th-century artists of the first rank began to shine brightly with the championship of the critic Champfleury (Jules François Felix Fleury-Husson, 1821-89) in the mid-19th century. (He did for the Le Nains what Thoré-Bürger did for Vermeer.)

Three major exhibitions—in London in 1910 (when Robert Witt distinguished the three by name) and in Paris in 1934 and 1978 (when Jacques Thuillier produced the then definitive catalogue)—firmly established their canonicity. (Pierre Rosenberg wrote a catalogue raisonné in 1993 and Neil MacGregor has made a significant contribution to the literature in recent times.)

In generic or thematic terms, the brothers' paintings roughly fall into three broad areas of subject matter: a few small, multi-figure oil-on-copper paintings; the main corpus of larger, oil-on-canvas works (religious scenes, genre-like paintings and portraits); and the paintings of peasants, for which they have been best known. The works in all these groups present iconographical problems. Many evidently made for the market lack early provenances and are thus deprived of contexts.

In the Le Nain Mystery’s US iterations at the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, and the Fine Arts Museum, San Francisco, its organisers, C.D. Dickerson, the head of sculpture and decorative arts at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, and Esther Bell, the curator of European paintings at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, arranged the paintings categorically: religious works (private and public), allegories, portraits, indoor and outdoor scenes, card players and children. A discrete section was devoted to The Forge (around 1640), a hapax legomenon of Le Nain painting. It combines many generic Le Nain characteristics—peasantry, portraiture, an interior/outdoor setting, possible religious references—but its subject, despite the title, is unclassifiable. And it has an unbroken provenance, to boot.

In Lens, in sharp and bold contrast to the US shows, the Louvre curator, Nicolas Milovanovic, has daringly and controversially arranged the works in differently coloured sections of the airplane hangar-like exhibition building by attribution, with galleries devoted to each brother. Because Mathieu lived on for nearly 20 years after his brothers' deaths, it has been slightly easier to distinguish his works, but Milovanovic's sifting of all three has been predominantly connoisseurial, with assays of circumstantial evidence such as it exists.

His argument, grosso modo, is that the middle brother, Louis, about whom the least is known, is the most prolific and distinguished of the brothers. His work is characterised by cool, subdued and subtle colours (Allegory of Victory, around 1635), free but controlled brushwork, a tendency for classicising (Venus in the Forge of Vulcan, 1641) and a feeling for landscape (to be seen in the backgrounds of his religious canvases). To him is also given the main hand in several religious paintings (The Penitent Magdalene, around 1643) and, above all, the many peasant scenes.

Milovanovic lays out, without positing any preference, various explanations for this strange fascination with the peasantry: to remind the city-dwellers of their country estates; to signal, in view of the uniformly sombre dress of the figures, Jansenist or Protestant sympathies; to satisfy the nostalgia of the recently urbanised bourgeois, or, conversely, like the contemporary Roman Bamboccianti, to smile at the yokels’ lack of polish. Anomalies abound in the details, as in the presence of courtly lap dogs and costly glass and ceramics. Louis’s sympathetic depictions of animals are also exceptional in a period not known for a concern for animal welfare (The Well, around 1641; The Donkey, around 1641). Little dogs and cats make regular appearances in all the brothers' paintings.

Antoine, the eldest, had been admitted as a master painter in the Corporation of Painters in St-Germain-des-Prés, which enabled him to open and maintain the studio in which his younger brothers worked. A source mentions him as a portraitist and a miniaturist, a clue that Milovanovic pursues to make the case that it is Antoine who created the small-format works on wood and copper notable for their brilliant colours and highly refined brushwork. A place of honour is given to a miniature, oil-on-leather portrait from 1638-40 of Henry of Lorraine, Count of Harcourt (1601-66), which only came to light in a Parisian family collection during the research for this exhibition. While Antoine's compositions can be crude, his figures are carefully delineated, as would be expected of a portraitist.

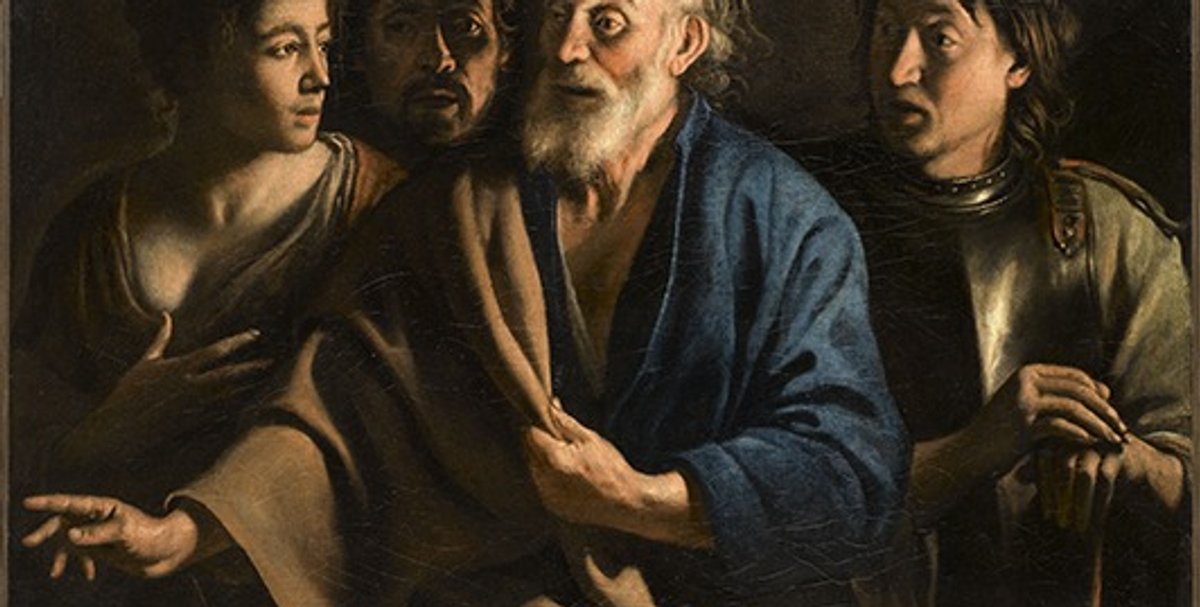

Mathieu is dubbed ambitious in view of his social ambitions, but his large religious works (with strong Caravaggesque tendencies) were also aimed at prominent public display (The Denial of St Peter, around 1655; The Last Supper, around 1655). By subtracting the works attributed to Antoine and Louis, and taking 1648 as a status post quo, Mathieu's style is easier to observe: contrasting colours, soft forms and dense brushwork with bright accents. In his later years his canvases include large numbers of figures, but his brushwork and compositional powers declined.

As attributions have been so long contested, it is more than appropriate that a section has been set aside for those painters whose works have in the past been attributed to the brothers, a couple of whom have now been identified (Jean Michelin, Alexandre Montallier). Most of these works, often assigned in the past but now clearly not by any of the Le Nains, have been given generic identities according to thematic links. The final room sets out some of the paintings that, since the 19th century, have been most contested by the great Le Nain scholars.

This exhibition will undoubtedly be the last word on the Le Nain brothers for many years to come and will, one hopes, stir scholarly debate and further research. Its only drawback is that it is in Lens. Despite the Louvre’s attempt at a “Bilbao effect”, the town and the Pas de Calais remain a backwater. But one must bear in mind that the Le Nain Mystery is a once-in-a-lifetime exhibition. Vaut bien le detour!

Donald Lee is the Literary editor of The Art Newspaper

The Le Nain Mystery, Louvre-Lens, until 26 June