Within two generations during the 19th century, the Rothschild family left behind the restricted life of the Jewish quarter in Frankfurt, to become bankers to the world—a transformation that was swiftly followed by investment in art to demonstrate their arrival as a new European dynasty.

James de Rothschild (1792-1868), the founder of the French branch of the family, was an energetic and talented man of affairs, closely involved in projects that modernised France, who helped to make Paris the financial capital of Europe. (His four brothers founded branches of the family business in Frankfurt, London, Vienna and Naples.) He also set the pattern for the characteristic Rothschild blend of collecting, philanthropy and charitable giving, which is the subject of Les Rothschild: une Dynastie de Mécènes en France, 1873-2016.

This large-scale and complex study, put together under the direction of Pauline Prévost-Marcilhacy, brings together an impressive array of specialists to analyse the 20,000 works of art given to more than 200 French public institutions by different members of the Rothschild family between 1873 and 2006. The first volume covers the years 1873-1922, the second 1922-1935, and the third 1935 to the present. They include a wide range of manuscripts, books, archaeological artefacts and works of art from around the world, culminating in Élie de Rothschild’s 1980 gift to the Centre Pompidou in Paris of Yolande Fièvre’s masterpiece, Festival pour oublier (1961). The Louvre and the Bibliothèque Nationale are heavily represented, reflecting the Rothschilds’ wish to identify themselves with—as James’s son Alphonse put it in his will—“the nation to which I have the good fortune to belong”.

The family was also a major force in the creation and development of regional collections and in public education in the realm of art. Rothschild women were major collectors, patrons and donors, from Charlotte (1825-99) to Alix (1911-87) and Béatrice Rosenberg, daughter of the French banker and philanthropist Alain de Rothschild. Charlotte donated the Strauss collection of Jewish religious objects to the Musée de Cluny in 1890, a gift of international significance, which deserves to be more widely known. Some of these donations are famous but others have rarely been photographed, studied or displayed, which makes these volumes invaluable in surveying every aspect of the Rothschilds’ artistic benevolence, spanning 150 years.

Unprecedented generosity on the part of four generations of one family took various forms: gifts, foundation collections, donations to settle tax bills, bequests, commissions immediately given to a public institution, assistance with acquisitions and support for excavations, with the finds going to the Louvre. The Rothschilds were discreet about acquisitions and their provenances, which makes the concentration on unpublished documents particularly welcome here. The Rothschild Archive in London and the Archives Nationales in Paris are the principal sources for the inventories, letters, photographs and other documents, discussed here in detail alongside the objects, making this a model study of its kind.

Each section is dedicated to a particular Rothschild, their collections and their benefactions, and starts with a short biographical study, followed by an essay or series of essays written by specialists. They reveal not only the personality and networks of each individual, but the nature of the art market in which they operated and the dealers on whom they relied. The first volume, and half of the third, is dominated by the extraordinary figure of James de Rothschild’s son Edmond (1845-1934), the most scholarly and authoritative of all Rothschild collectors, whose gifts transformed the national collections in his lifetime from 1873 and beyond, thanks to the generosity of his children. No less than 14 essays are dedicated to the so-called “Musée de la gravure”, its formation, contents, critical fortunes and installation in the Louvre.

Edmond’s brother Alphonse (1827-1905) emerges clearly from the first two volumes as a very different, complementary personality to Edmond: a public figure and financier who inherited the leadership of the French Rothschild banking empire from his father and who, through his marriage to his cousin Leonora, retained close links with the English branch of the family. He emerges as a patron of contemporary art—not least the sculptor Camille Claudel—on behalf of regional museums in France, as a lender to public art exhibitions and as a role model for private collectors and their contribution to the public realm at a time of marked anti-Semitism, culminating in the Dreyfus affair from 1894.

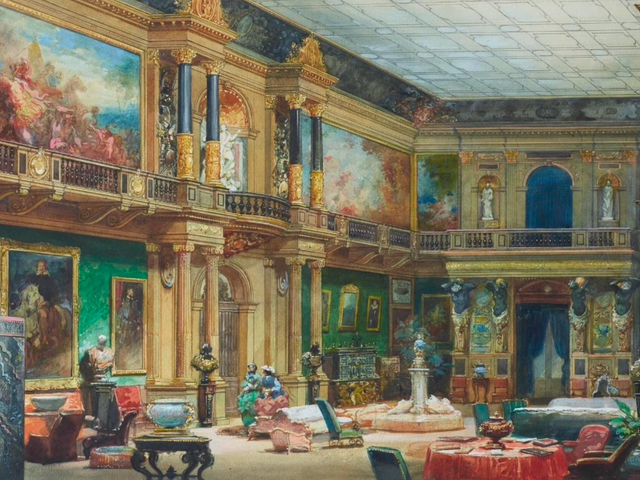

The collection of work by European goldsmiths from around 1500 amassed by Adolphe Carl von Rothschild (1823-1900) is analysed in detail by Philippe Malgouyres and Elisabeth Antoine-König, in terms of his bequest of 1901 to the Louvre and the Cluny. Collecting Christian liturgical objects rather than devotional pieces allowed Adolphe to keep “a certain distance” from Christianity as a Jewish donor of Christian art. These pieces included superb jewels and boxwood microcarvings, which he regarded as “the best and the most precious” of all his art objects. They had a distinct identity and were always kept separately in the smoking room of his house in Paris. In his collecting tastes, Adolphe showed a close affinity with his English cousin Ferdinand (1839-98), whose Waddesdon Bequest was willed to the British Museum in 1897. Both sought to identify themselves with the history of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance as a way of entering the public life of countries whose citizenships they had adopted.

The cumulative impression made by the three volumes is of the strong Rothschild concern that private collections should become part of the national story and serve as a key element in public education. In the words of the newspaper Le Jour in 1891: “Art and charity will be the motto that history will inscribe before the name of this great family.”

• Dora Thornton is the curator of the Waddesdon Bequest at the British Museum, for which she organised a new gallery in 2015, funded by the Rothschild Foundation. Her book A Rothschild Renaissance: Treasures from the Waddesdon Bequest (British Museum Press) was published to accompany the opening

Les Rothschild: une Dynastie de Mécènes en France, 1873-2016

Pauline Prévost-Marcilhacy, Marc Bascou, Marianne Grivel, Isabelle Le Masne de Chermont and Pascal Torres

Somogy Editions d’Art, three volumes, 1,112pp, €290 (hb, cased)