Kenya has made it to the Venice Biennale, despite receiving none of the money promised by its government for its national pavilion.

At the opening of the Kenya pavilion last Friday, 12 May, the curator Simon Njami, who has acted as the project adviser, described it as “a miracle”, adding: “The fact that we are here is in itself a success.”

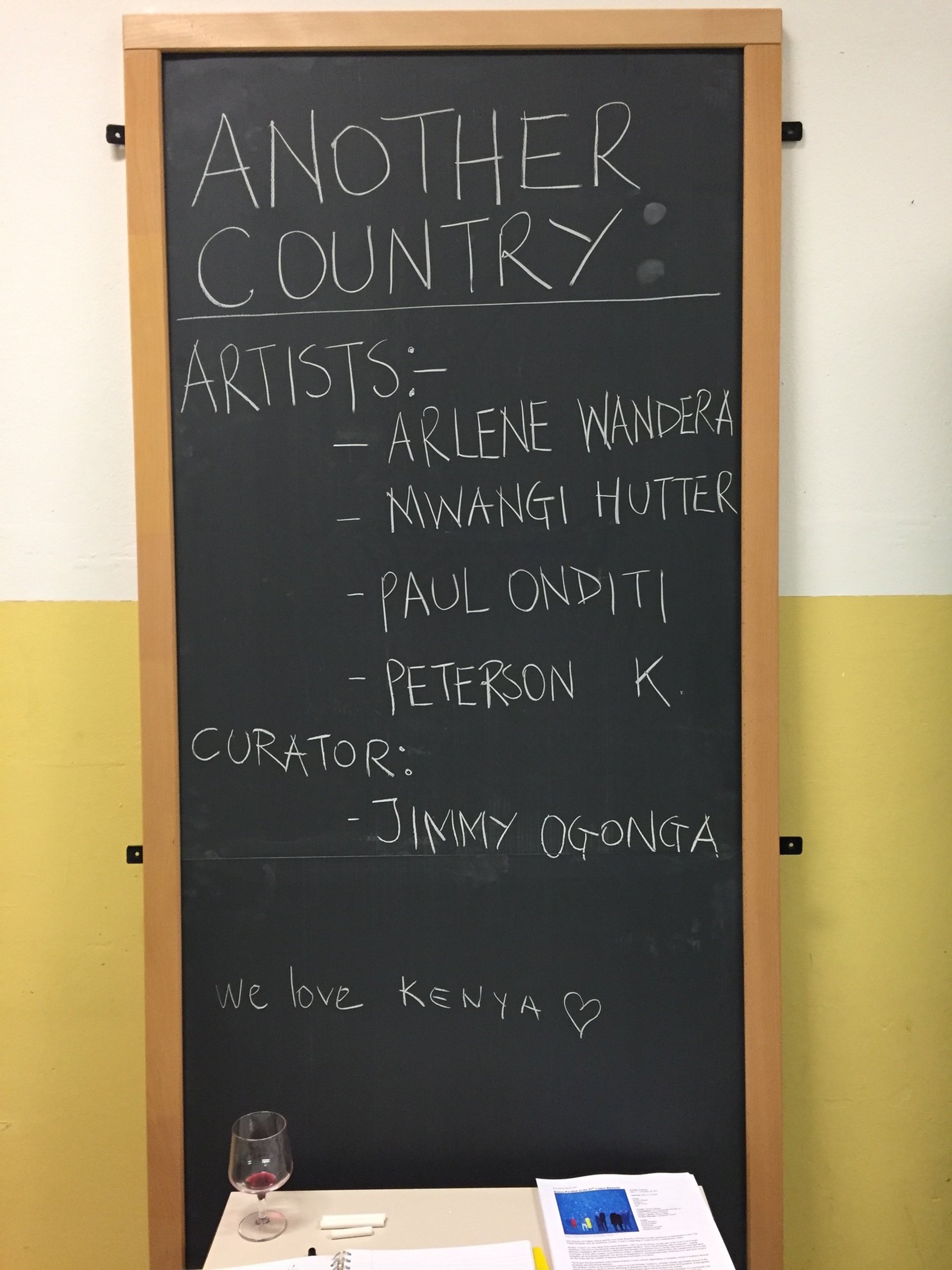

Just a few weeks ago, Jimmy Ogonga, the pavilion’s curator, was forced to embark on a frantic fundraising effort after the money pledged by the Kenyan government failed to materialise. The Biennale was even informed that the show would be cancelled—Kenya is not included on the Biennale website’s list of participating foreign nations.

“It has been a long, harsh journey to get here,” Ogonga says. “We found ourselves in a situation where out of nothing, out of a zero budget, we had to put together a pavilion.”

First, Ogonga teamed up with a partner in Venice, Zuecca Project Space, a non-profit organisation that helps develop Biennale events. Zuecca secured the disused third floor of a school at the back of the island of Giudecca for the Kenyan show.

Meanwhile, a supporter who runs an artist residency programme on the island of Lamu, off the southeast coast of Kenya, pitched in to pay for three airplane tickets, and the coffee company Hausbrandt agreed to fund the Kenyans’ accommodation in Venice. The artists made their own way to Italy.

Most artists representing their countries in Venice have months to examine the building where their work will be shown, but Arlene Wandera, one of the four participating Kenyan artists, saw the space her work now occupies just four days before the exhibition opened.

“I sat in this room all day and thought about how I could engage with it,” she told The Art Newspaper while standing in a third-floor classroom of the Palladio school. She has placed a ladder with tiny sculptures of men balanced atop a beam placed on the ladder’s lower rung while another figure dangles from a wire. In one corner of the room stands a wooden door frame recovered from the school. All the windows are open, revealing sweeping views of Venice.

A video and paintings by other Kenyan artists are on display in nearby rooms.

Kenyan, not Chinese

Kenya’s first official Venice Biennale pavilion in 2013 caused widespread controversy because it showed works by one Italian and eight Chinese artists, and just two Kenyan artists. The display was curated by two Italians.

In 2015, the Kenyan pavilion, curated by the same Italian duo, showed the work of six Chinese artists, two Kenyans and an Italian. It was denounced by the Kenyan government after artists launched an online petition calling on the country’s ministry of sports, culture and the arts to “renounce Kenya’s fraudulent representation… and commit to support the realisation of a national pavilion in 2017”.

The government subsequently withdrew the right for the Kenyan flag and the Biennale logo to be used to promote the show. The Financial Times later revealed that the display had been funded by Yan Lugen, a Chinese real estate developer, collector and investor in art.

Ogonga describes these past exhibitions as “illegitimate”, adding: “There were questions of representation, integrity, transparency and so on.” This time the Kenyan pavilion has “basically no money”, he says. “It may not be the grandest exhibition, but it is ours.”

The Kenyans will use their pavilion, which is loosely inspired by James Baldwin’s 1962 novel Another Country, for a public programme which will engage with the children in the Palladio school and the wider community on Giudecca. Kenyan artists will travel to Venice for residencies, and there are plans for lectures, screenings and site-specific works to be installed in and around the school. Wandera hopes to set up a studio in the school in September and spend three months in Venice hosting workshops for the schoolchildren and the wider community.

“This exhibition is just the beginning,” Ogonga says.