Christine Macel says that she has “constructed Viva Arte Viva like a journey, an experience, that leads you through the exhibition”. It starts in the Giardini in the central pavilion (the former Padiglione Italia) and then moves to the 320m-long, 14th-century Corderie (rope factory) in the Arsenale, finishing in the gardens at the end of the complex. It is divided into nine themed sections, which Macel calls “trans-pavilions” that “put the voice, the role and the responsibilities of the artist at its centre”.

Central Pavilion, Giardini

One Pavilion of Artists and Nooks

Making art is about making time to think, Macel seems to be saying. The commercial world is all about increasing productivity; as a reaction to this, we see in photos the late artist Franz West hanging out with his friends and napping on the sofa. Meanwhile, Olafur Eliasson is inviting some of the many recent migrants to Italy to take part in a studio project.

Two Pavilion of Joys and Fears

“Emotions are central to artists’ work, but strangely denied in the critical discourse around art of the past 40 or so years,” Macel says. Joy, fear, intimacy and claustrophobia are among the topics addressed by artists including Tibor Hajas, the late Hungarian modernist, and Marwan, the Syrian artist who died last year. Younger artists include Rachel Rose, the New York film-maker.

Corderie, Arsenale

Three Pavilion of the Common

People like to do things together is the theme of this section of the exhibition. In 1981, the late Italian artist Maria Lai involved her whole village of Lanusei in a performance, linking it to the mountains with a single blue ribbon. Meanwhile, Colombian artist Marcos Ávila Forero enacts a performance based on African traditions. “It’s about something we can enjoy together in a postcolonial era,” says Macel.

Four Pavilion of the Earth

The environment, communitarianism and ecological movements are at the centre of this phase of the show. Artists include Bonnie Ora Sherk, the San Francisco and New York-based landscape architect and performance artist who famously ate lunch with caged animals in a zoo in the 1970s, and Kananginak Pootoogook, the late Inuit artist.

Five Pavilion of Traditions

“Tradition isn’t much discussed by theorists these days because it is seen as conservative and antithetical to Modernism, because its only tradition is rupture,” says Macel, “but that doesn’t mean it isn’t interesting to artists.” This section includes work by Hao Liang, the Beijing-based artist who draws on traditional ink painting techniques.

Six Pavilion of the Shamans

Marcel Duchamp has been the dominant figure in late 20th and 21st-century art, but Macel is restating the case for the influence of Joseph Beuys. “The idea of a pavilion of the shamans was suggested by several artists—the idea of the artist as a visionary,” she says. In 2014, the Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto journeyed to meet the Huni Kuin people in the Amazon jungle, and he is showing work inspired by their shamanic rituals.

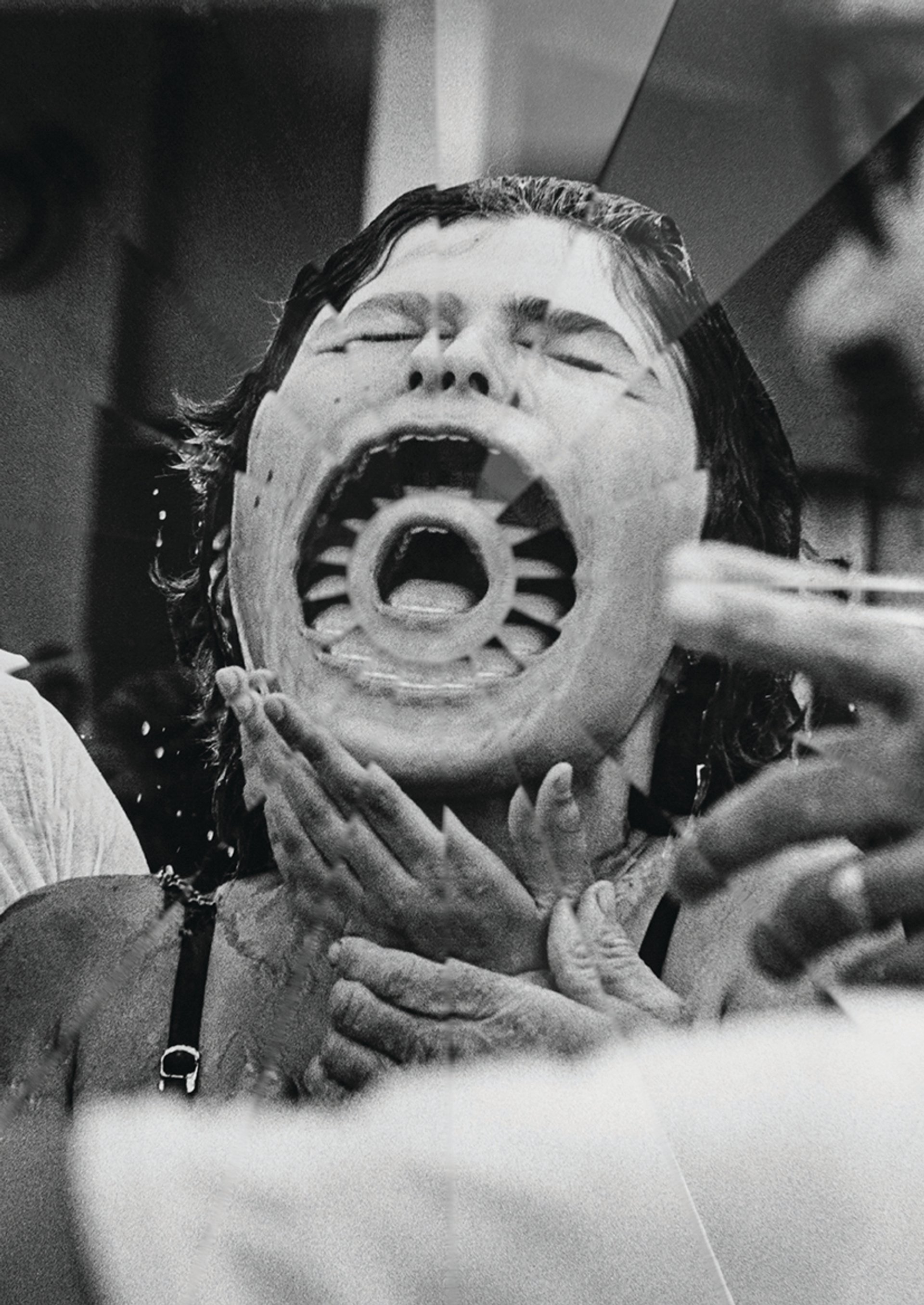

Seven Dionysian Pavilion

Sex and drugs and rock‘n’roll… well, maybe not rock‘n’roll. Macel promises us a celebration of female sensuality, including work by Huguette Caland, the Lebanese-born, Los Angeles-based artist known for her decorative paintings, body sculptures and line drawings, as well as photographs by Eileen Quinlan, the US artist. Meanwhile, the Berlin-based Canadian artist Jeremy Shaw is showing works that examine religious trances and other states of altered consciousness. “It is about the state of being out of oneself—the Latin root of the word ecstasy,” says Macel.

Eight Pavilion of Colours

Macel says that the pavilion of colours is the “fireworks” at the end of Corderie, bringing together ideas such as the subjective nature of perception, the ability of art to generate emotion, and even the political connotations of colour. Artists such as Giorgio Griffa, the Italian abstract painter whom Macel calls “one of the greatest living painters today and who hasn’t been seen in the Biennale since the 1970s”, is addressing “spiritual issues”. Karla Black, the Scottish artist who makes pastel sculptures out of materials such as make-up, sugar and chalk also features, in a work Macel describes as “sensual and haptic”.

Nine Pavilion of Time and Infinity

The exhibition finishes in the Giardino delle Vergini with its most most mysterious phase—a mix of performances and installations in the winding garden at the end of the Arsenale and in the strange, rough storerooms hidden against the site’s back wall. Works such as Edith Dekyndt’s One Thousand and One Nights (a performance in which dust is brushed into an ever moving square of light on the gallery floor) meditate on time, infinity, the metaphysical—and inevitably death. “It is dealing with repetition, variation, permanence and impermanence—it’s an open conclusion to the whole show,” Macel promises.