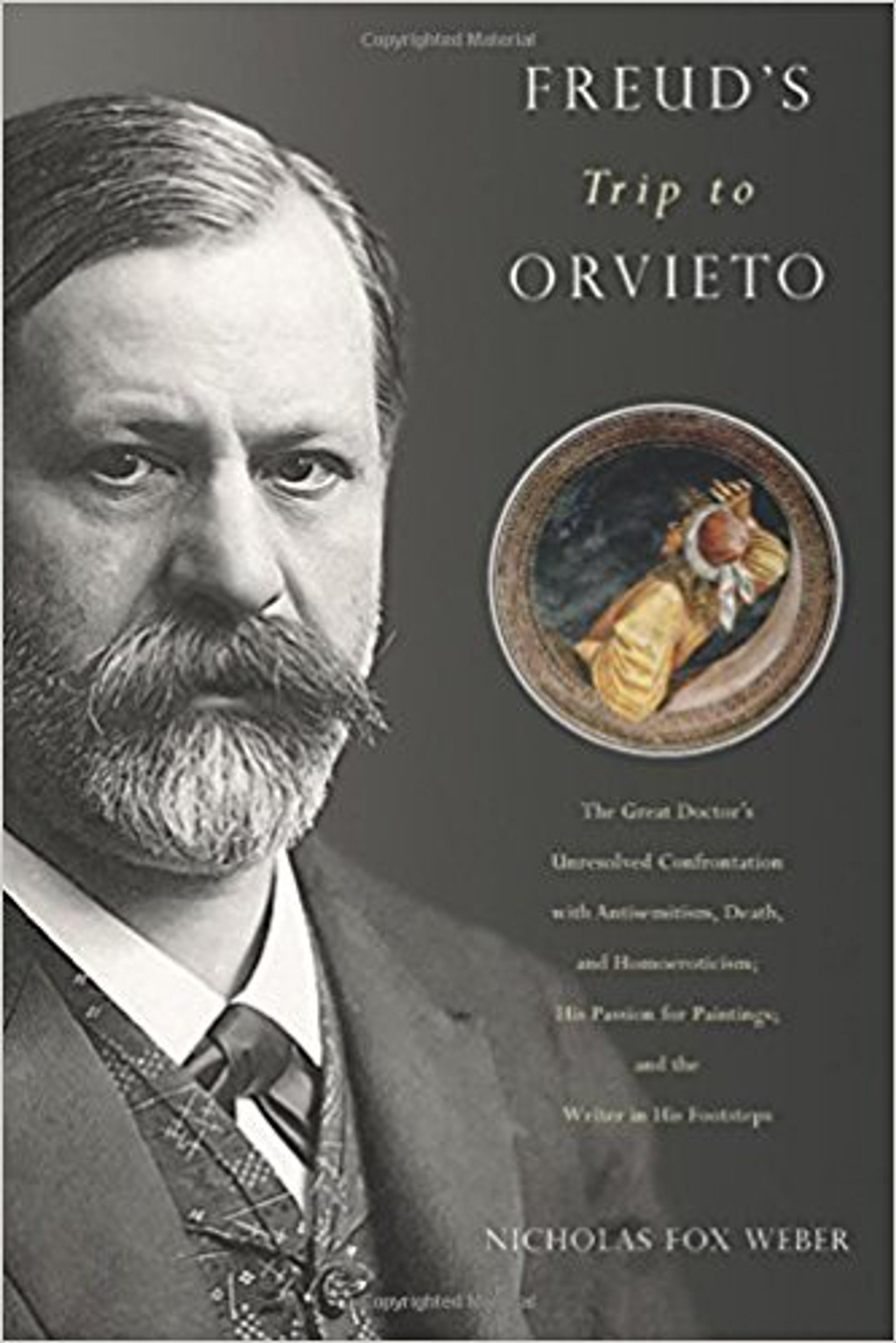

In the small Italian town of Orvieto in 1897, Sigmund Freud had a revelation. In the town’s cathedral, before a depiction of the Last Judgement by the Renaissance painter Luca Signorelli, the 41-year-old psychoanalyst felt he had found “the greatest” depiction of the theme he had ever seen. The intense and violent fresco, which carries an odd sexual energy, was seared into his mind. Yet upon his departure, “to his immense frustration, Freud could not recall the name of the artist,” writes Nicholas Fox Weber, in his new book, Freud’s Trip to Orvieto (Bellevue Literary Press).

Through 48 short, sharp chapters (some are only a page and a half), Weber traces the psychoanalyst’s memory loss and his attempt to recall Signorelli’s name. “To his amazement, Freud could, nonetheless, see certain details of the fresco cycle perfectly in his mind’s eye,” Weber writes, which frustrated the psychoanalyst even more. At first, Freud thought the work was by Sandro Boticelli or Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, but he then realised he was simply confusing their surnames. The episode became a key moment in his career, and he dubbed his confusion the “Signorelli Parapraxis”, which was meant to explain how forgetfulness can lead to substitution in a person’s memories.

Yet Weber’s book is not simply an academic study. Although he is the first writer on the subject to actually visit the cathedral at Orvieto and investigate the frescos for clues about Freud’s problem, he does not devote himself exclusively to these questions. Freud’s Trip to Orvieto is also a poignant memoir of Weber’s childhood, a revealing portrait of his intellectual development and a incisive study on masculinity and Judaism.

The book is 27 years in the making. In 1990, after Weber’s mother died, he was clearing away his parents’ library when—“tucked between two hardcover novels smelling of a mix of cigar and cigarette smoke”—he happened upon a reprint of a scholarly article written by family friends who were psychoanalysts, Richard and Marietta Karpe. The article was titled The Significance of Freud’s Trip to Orvieto, yet Weber’s initial interest in the article was not scholarly. Instead, it brought to mind a vivid scene from his childhood.

“At age 16, I became obsessed with a very seductive, very beautiful younger friend of my mother’s,” Weber says to explain the genesis of the book. “And she managed to make me feel very aware of what it meant to be a man when I was in puberty.” At a cocktail party thrown by his parents in 1964, he remembers watching this woman go up to the Karpes—“these Germanic, psychoanalytic types who looked very different from all the other people there”—to engage them in conversation. “She was the only person who had the panache and the originality to go up to them and have a conversation with these strangers,” he says. “When my mother died, that moment came back to me.”

Weber’s book thus pulls together a series of elegant portraits, freely combining art history with memoir and psychoanalysis. At one point, Weber argues that Freud was so compelled by Signorelli’s work because he felt that, as a Jew, he “belonged among the damned” who would be cast into hell in the artist’s depiction of the Last Judgement. The thought that Freud hated his own Judaism reminds Weber of a painful episode in his own life, when he failed to stand up to an art history lecturer at Yale University in 1971 who made an anti-Semitic remark. Weber writes regretfully that the incident briefly made him into “an observer rather than a participant in the fight against bigotry”.

In the afterward, he writes of struggling with certain phrasings while editing the book, noting that he wanted to “get past the euphemisms, masking, veiling, and the retreat from reality to the escape mechanism of convoluted language.” He adds: “I long for truthfulness, for simplicity, for authentic responses, for accepting the way things are, for calling a spade and spade, not just for accuracy but for a correction of myths.” Perhaps this is a slight stretch. Memoirs, no matter how well remembered, are still inventions, at least in part. Our memories are too faulty for pure recollection. Yet Weber is right about his book: it strikes one as truthful, clear and revealing.

• Freud’s Trip to Orvieto, by Nicholas Fox Weber, Bellevue Literary Press, $26.99 (hb)