Three great-grandchildren of Peggy Guggenheim are accusing the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation in New York of defying the wishes of the late collector. The museum’s current exhibition, Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim (until 6 September), celebrates collectors who helped shape the foundation. It includes 21 works from the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, from major works by Duchamp, Picasso and Brâncuși, to Jackson Pollock’s Alchemy (1947), one of the artist’s greatest “drip” paintings. But three of Peggy Guggenheim’s great-grandchildren say that when she donated her Venetian palace and Modern art collection to the foundation set up by her uncle in New York, she stipulated that none of the works on show in Venice should be removed for display elsewhere between Easter and 1 November.

“She wanted the work to be in Venice at that time every year because it is the high tourist season in the city, and every two years this period coincides with the biennale,” says Sindbad Rumney-Guggenheim, a great-grandson of Peggy’s, who says he also speaks on behalf of his two brothers and his father. This year, “many of the collection’s major works will be in New York. That’s going to be detrimental to any tourist who’s visiting the Peggy Guggenheim Collection.”

Ongoing dispute Rumney-Guggenheim and other family members descended from Peggy Guggenheim’s only daughter, Pegeen Vail, who predeceased her mother, have repeatedly sued the Guggenheim Foundation in French courts, arguing that the organisation has failed to respect Peggy’s wishes in its management of her collection. Their case has always been rejected, most recently by the Paris Court of Appeal in 2015.

The latest row boils down to a case of duelling documents. The condition related to the tourist season is outlined in a letter dated 27 January 1969 from Peggy Guggenheim to her cousin Harry, then the foundation’s president. The terms of this letter were accepted by Harry Guggenheim and his board of trustees and incorporated into a legal document known as an assignment, dated 8 October 1974, which sets out the terms by which the Peggy Guggenheim Foundation transferred ownership of its Modern art to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

The stipulation was referred to in other documents as well, including one version of Peggy Guggenheim’s will, dated 9 October 1972, which states that: “It has also been agreed… that none of [the] works of art shall be loaned to any institution during the period from 1 April to 31 October, annually, because during this period the collection has always been on display... in my palace and it was felt that the continuance of this policy would be most desirable.”

But this condition was not included in a deed of gift dated 23 January 1976, which Peggy Guggenheim and representatives of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation signed in the presence of an Italian notary. This document—which French courts have repeatedly found to be legally binding—does not specify any conditions attached to her gift.

Conditions or no conditions?

Other documents complicate the question further. In the past, the Guggenheim Foundation itself described the deed of gift as a formality required by Italian law and pointed to the correspondence between Peggy and Harry Guggenheim as the relevant documents that set out the terms of her donation.

A letter sent by the New York law firm White & Case on behalf of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation to the Inland Revenue Service on 5 February 1976, two weeks after the deed of gift had been notarised in Italy, states that the foundation “had been advised by Italian counsel” to obtain “Italian governmental approval” of the transfer of art and had therefore signed the deed of gift. But under the law of New York state, where both foundations are incorporated, according to the letter, “in our opinion... ownership to the [art] in question was acquired by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation in 1969, subject only to the conditions set forth in the 1969 exchange of letters.”

A spokeswoman for the Guggenheim Foundation says that the 1969 letter cited by Rumney-Guggenheim was Peggy Guggenheim’s initial proposal for her art donation, and that the legally binding document is the deed of gift, which was signed seven years later. “Mr Rumney’s claim that there were conditions to Peggy Guggenheim’s gift… has been rejected repeatedly by the courts,” she says. The 2015 judgement, like those of other courts before it, stipulates that the gift is “pursuant to the deed of 23 January 1976”, which contained no conditions.

She says the letter written by White & Case to the IRS has also been submitted to the courts, which concluded that the “operative document” is the deed of gift. “Whatever may have been argued to defend a tax dispute was not determined to be legally relevant,” she says.

The spokeswoman also notes that other members of the family—the grandchildren of Peggy Guggenheim’s son Michael Sindbad Vail, who was the sole heir and executor of her estate—have not joined any of the lawsuits, and some have written letters supporting the foundation. Furthermore, she says that the works donated by Peggy Guggenheim on show in New York are part of the foundation’s own collection. “No loans are involved,” she says.

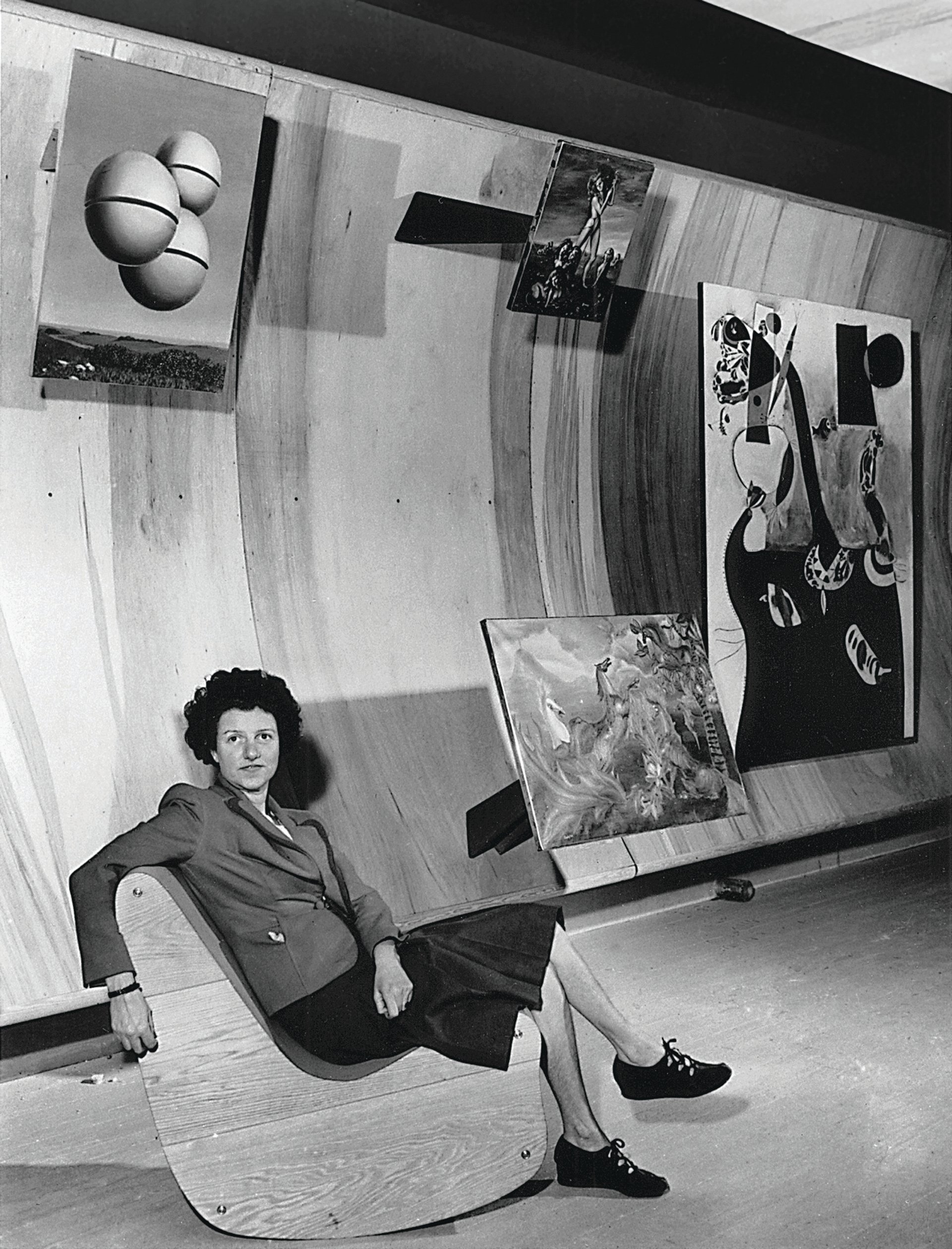

A great collector Born in New York, Peggy Guggenheim (1898-1979) was 21 when she inherited her share of the mining fortune of her father, Benjamin Guggenheim, who died in the sinking of the Titanic. She moved to Paris a year later and lived among avant-garde artists and writers. Between 1938 and 1942, she opened galleries in London and New York, where she helped establish the careers of artists such as Jackson Pollock and Max Ernst (she was briefly married to the latter). By 1949, she was living in the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni on the Grand Canal in Venice, where she displayed her collection of Modern art.