A rare Dutch Golden Age map of the world that was discovered, scrunched up in a ball, in a house in Aberdeenshire is on show at the National Library of Scotland (until 17 April). Claire Thomson, a conservator at the library, describes its preservation as “the most difficult project I have ever tackled”.

Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula (new map of all the world) was designed by the Amsterdam-based cartographer Gerald Valck and was probably published in London by George Wildey in around 1690. It is similar to the highly decorated maps that hang on the walls in some of Vermeer’s paintings. Until now, only two copies of Valck’s map were known: one is in the British Library in London and the other is in the Maritime Museum Rotterdam. The more than 2m-wide “chimney map”, named because it was probably found in a chimney, was printed from copper plates in eight sections and pasted onto a linen backing.

The map was discovered by builders renovating an old house. The precise circumstances remain obscure, but initially it was said to have been found rolled up and inserted into a chimney, probably to prevent draughts. More recent reports suggest that it was in a roof void in a historic house. Seeds and insect remains were found inside the map, which suggests that it had become home to rodents or birds.

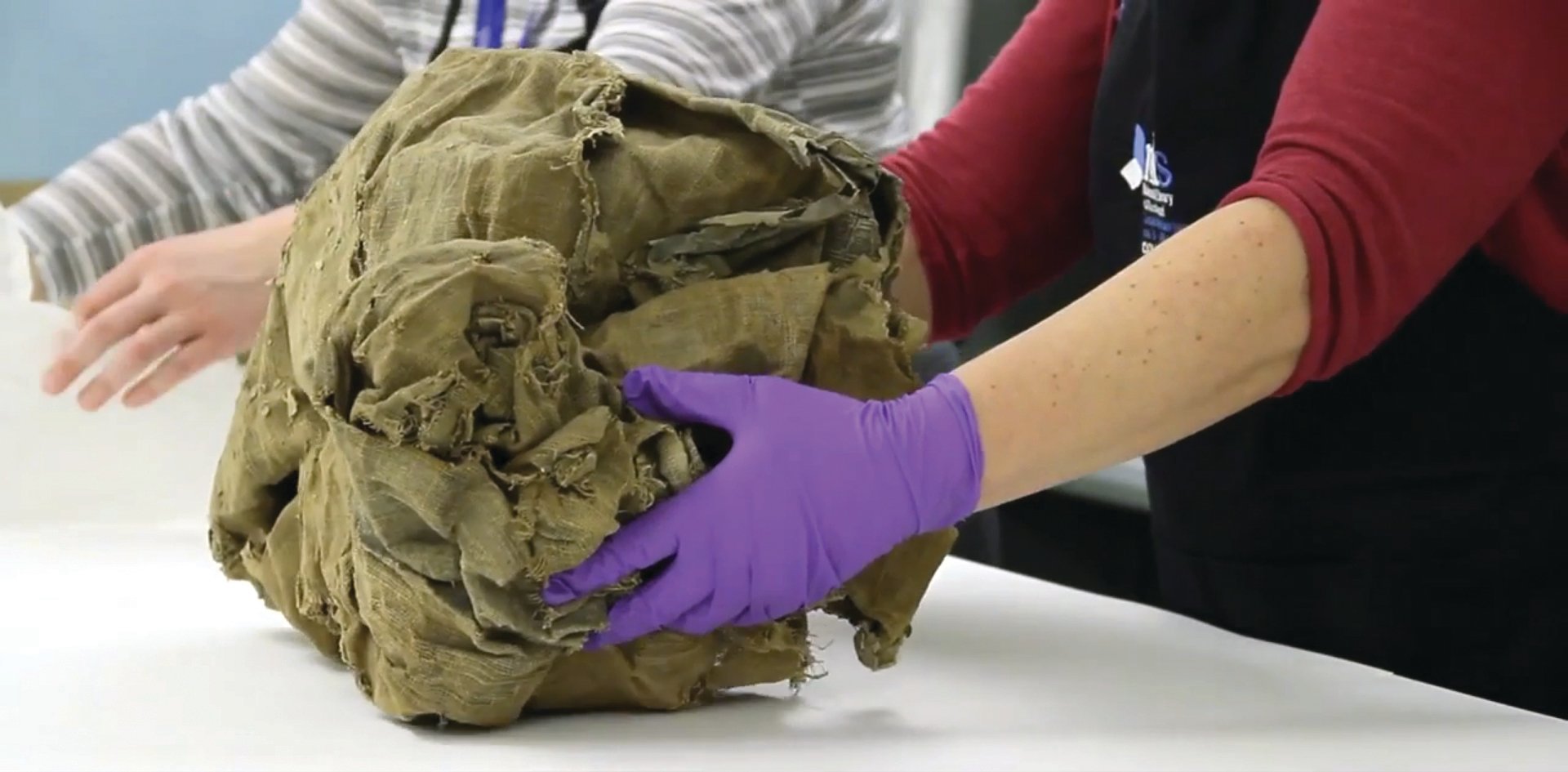

The scrunched-up ball was about to be thrown into a skip, until someone took an interest in it. The map was later given to Brian Crossen, a geography teacher, who donated it to the National Library of Scotland in 2007.

Almost half of it had been lost, and the remainder was torn, distorted, dirty and extremely fragile. Thomson’s first step was to gently untangle the ball and to partially stretch it out with light weights. Gelatine was used to moisten the old adhesive and the map was separated into its eight sections.

The sections were then placed in a humidifying chamber, to relax the paper and make it possible to open the folds and gradually flatten the map. The eight pieces were then dried under weighted boards. Next, Japanese paper was temporarily applied to the front with a seaweed adhesive, making it possible to undertake the most difficult task, that of removing the original linen backing. Fortunately, the inks and pigments were not water-soluble, so sections could be washed for one hour. The final step was to mount the eight sections together on a new paper lining. No attempt was made to fill in the missing areas. A full account of the conservation appears in the January issue of Icon News.

The restored map, which is now being digitised, will be displayed in Edinburgh for six weeks (long-term display would be unwise from a conservation standpoint). It will then be put into storage, loosely rolled because of its size.