The 78th edition of the Whitney Biennial opens this month—the first in the museum’s Renzo Piano-designed home in New York’s Meatpacking District.

Launched in 1932 by the museum’s founder, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, as a survey of contemporary American art, the show “attempts to take a snapshot of the moment”, says Mia Locks, an independent curator who has co- organised the forthcoming show with Christopher Lew, an associate curator at the Whitney.

Locks and Lew travelled around the US and Puerto Rico to select the 63 artists in the show, who were born between the 1920s and 1990s and working in an array of media, including painting, photography, video, sculpture and film.

The show’s organisers aimed for a wide definition of American art: the roster includes artists based in the US, irrespective of original nationality, and American-born artists living abroad, such as Jo Baer (who had a solo show at the Whitney in 1975, and whose Amsterdam studio the curators visited). Also included are collectives such as GCC, which was founded in Dubai but also has members in the US. Some of the show’s themes, such as violence, inequality and how artists make work in a time of uncertainty, came up during studio visits.

This will be the largest-ever Whitney Biennial in terms of square footage, occupying around two-thirds of the museum’s exhibition space, which allows “breathing room for the works”, Locks says. Multiple site-specific installations, such as the Los Angeles-based artist Rafa Esparza’s immersive room made from tens of thousands of adobe bricks baked in the sun, are included in the show.

We spoke to three artists included in the show about their work and the usefulness of the term “American art”.

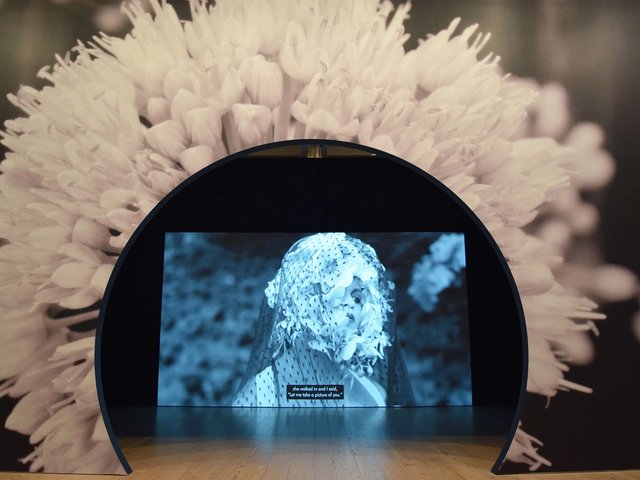

An-My Lê: “I was asked to photograph in the [American] South last May, at a time when Confederate monuments were being contested and people wanted to take them down. I thought there was a great relationship between the film set [that I shot, of Gary Ross’s movie Free State of Jones, about a Confederate army deserter] and these monuments and this idea of history. Even though it is memorialised, somehow there’s something still really raw about it. There are repercussions and it’s still filtering and affecting everyday life, and this kind of recycling and reopening of old wounds is interesting to me.” V.S.B.

John Divola: “There is nothing objective—it is a matter of opinion and perspective. What it means to ‘be American’ is always shifting, though perhaps more dramatically recently. Certainly, there was a shift with Obama as well. I am not encouraged by recent events but the course of a nation has its ebbs and flows. As a photographer, my work is always rooted in a specific location—time, place and circumstance—but cannot help but be influenced by the instantaneous international flow of images and information.” J.S.

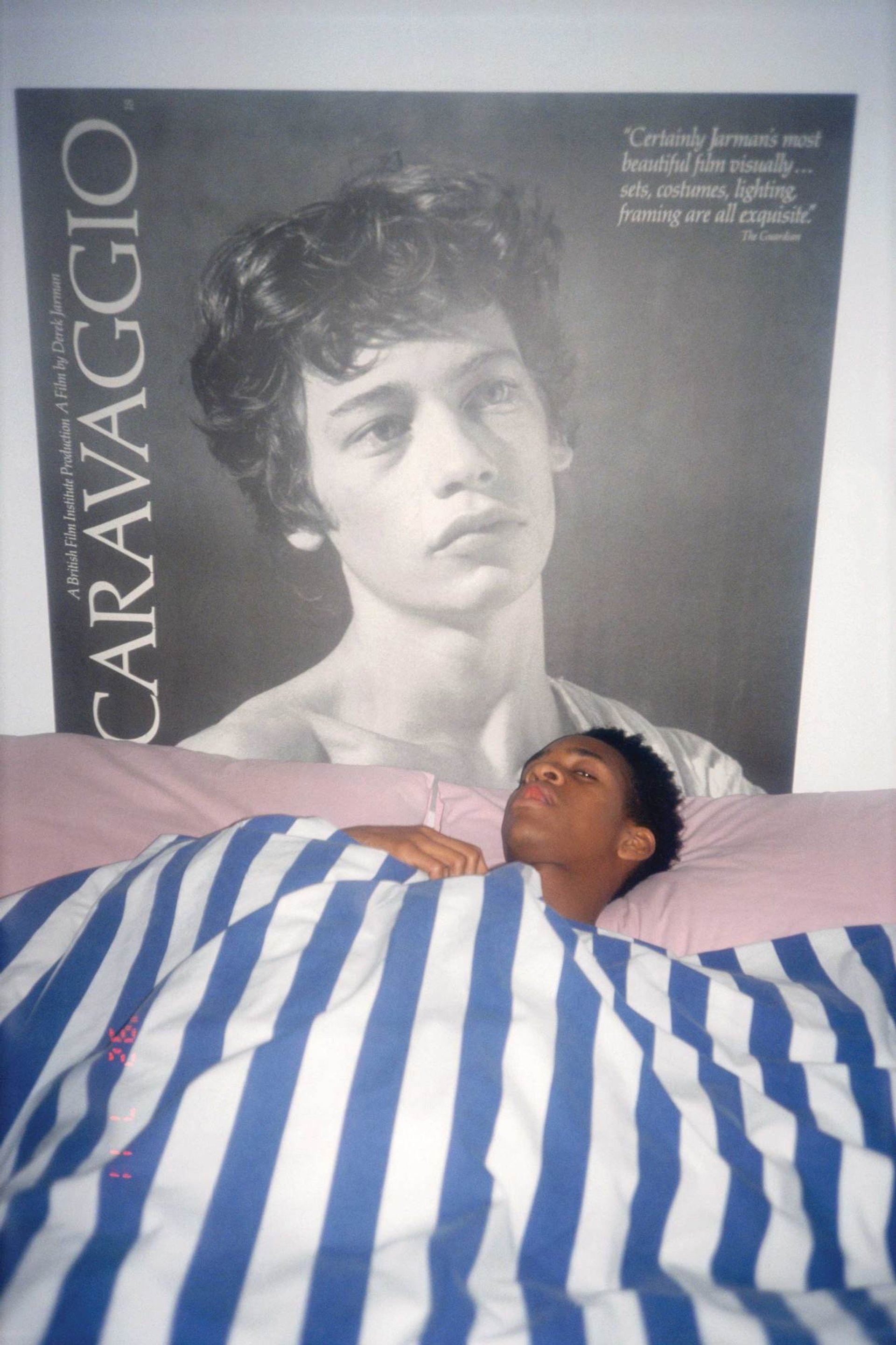

Lyle Ashton Harris: “The notion of America is being debated right now and it’s smart and important to expand what defines it. There is a fluidity to identity. I was concerned when [Once, Once, a 2016 work using images from the artist’s archive and related to his Whitney installation] was shown in Brazil at the Bienal de São Paulo last year, about whether it would translate. And it translated quite well. It’s a work from the mid-1980s and it resonates today. Cultural specificity is local, but it has a global reach as well. Recognition beyond the border: for me, that’s what makes something successful.” P.P.

• Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 17 March-11 June