Tension, upheaval, uncertainty, disorientation: do these themes sound familiar? They are the persistent refrain of many recent biennials because they are the persistent problems of our time. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev made trauma the key issue of Documenta 13 in Kassel in 2012 and last year’s Venice Biennale, organised by Okwui Enwezor, imagined a sprawling capitalist wreck. “Here we are,” he wrote in the catalogue essay, “standing, puzzled, looking with scrutiny at the inscrutable; a plateau of debris stretching across the horizon.”

The 2017 Whitney Biennial—which is not really organised around a theme but serves as a cross-section of recent artistic production in America—keeps up the general insistence on disorder but the tone is milder, both conceptually and formally. The curators Christopher Lew and Mia Locks organised their exhibition largely in the lead-up to the 2016 American presidential election, which was in many ways a grand liberal opportunity. The fallout of that historic upset is largely unreflected in the show, in part because by the time the results came in on 8 November, most of the artists and their work had been selected and commissioned. A wall text at the museum says the biennial “arrives at a time rife with racial tensions, economic inequities, and polarizing politics,” which is true. But the sense of alarm seems sometimes like an afterthought, as if Lew and Locks—like more than half the country—expected a different presidential outcome.

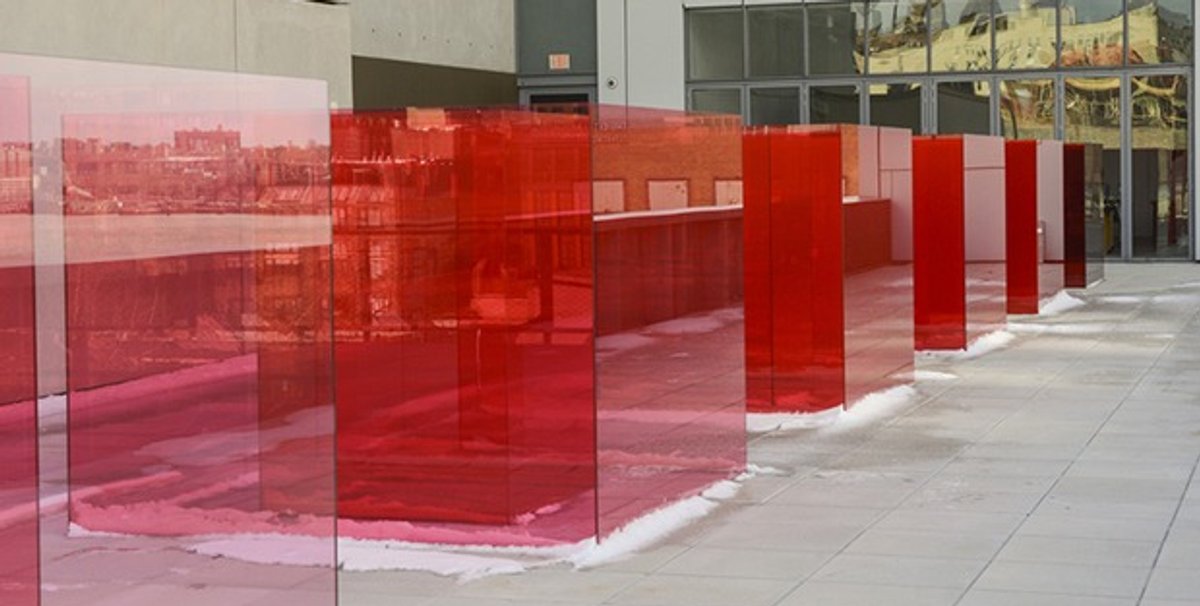

This likely explains the inclusion of some of the most handsome works in the show, such as Matt Browning’s sculpted grids, delicately and exactly whittled from single pieces of wood. In the current context, however, this handicraft tradition could seem quaint. The same goes for Ulrike Müller’s lovely wool tapestry of a cat, which would look good practically anywhere. On the other hand, Larry Bell’s installation Pacific Red II (2017) would not look as well in, say, a basement as it does on the museum’s open-air fifth floor terrace, where the sun illuminates Bell’s red glass boxes, each of which appears a shade brighter than the one before. It is an optimistic work and proves that the Minimalist Old Masters still have power. It is also reminder that a show without any hopefulness would be unbearable. But it does not carry the disquiet one would expect from a work created so recently.

Adam Weinberg, the Whitney’s director, suggested in a press conference that irony was absent from this show. But then how to explain Jon Kessler’s ridiculous sculpture Exodus (2016), in which a few dozen kitsch figurines, including one of a man happily reading a book, are set on a spinning pedestal going round and round in “exile”. Does Kessler really believe that Syrian refugees fleeing Aleppo look like that ornament of the old woman gladly carrying flowers? Irony is a poor tool, and offensive when the situation is deadly serious.

The better works about migration instil a sense of unease, as in Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s film The Island (2017). The 42-minute video tells the story of Pulau Bidong, an island off the coast of Malaysia that was, during the Vietnam War, the world’s largest refugee camp. Nguyen fictionalises the narrative by setting it in the future, just after the island had become the home of the final two survivors of a nuclear holocaust. Nguyen melds in a story in about a woman whose fishing boat was turned away from Pulau Bidong in the days of the Vietnam War and her return, under cover of night.

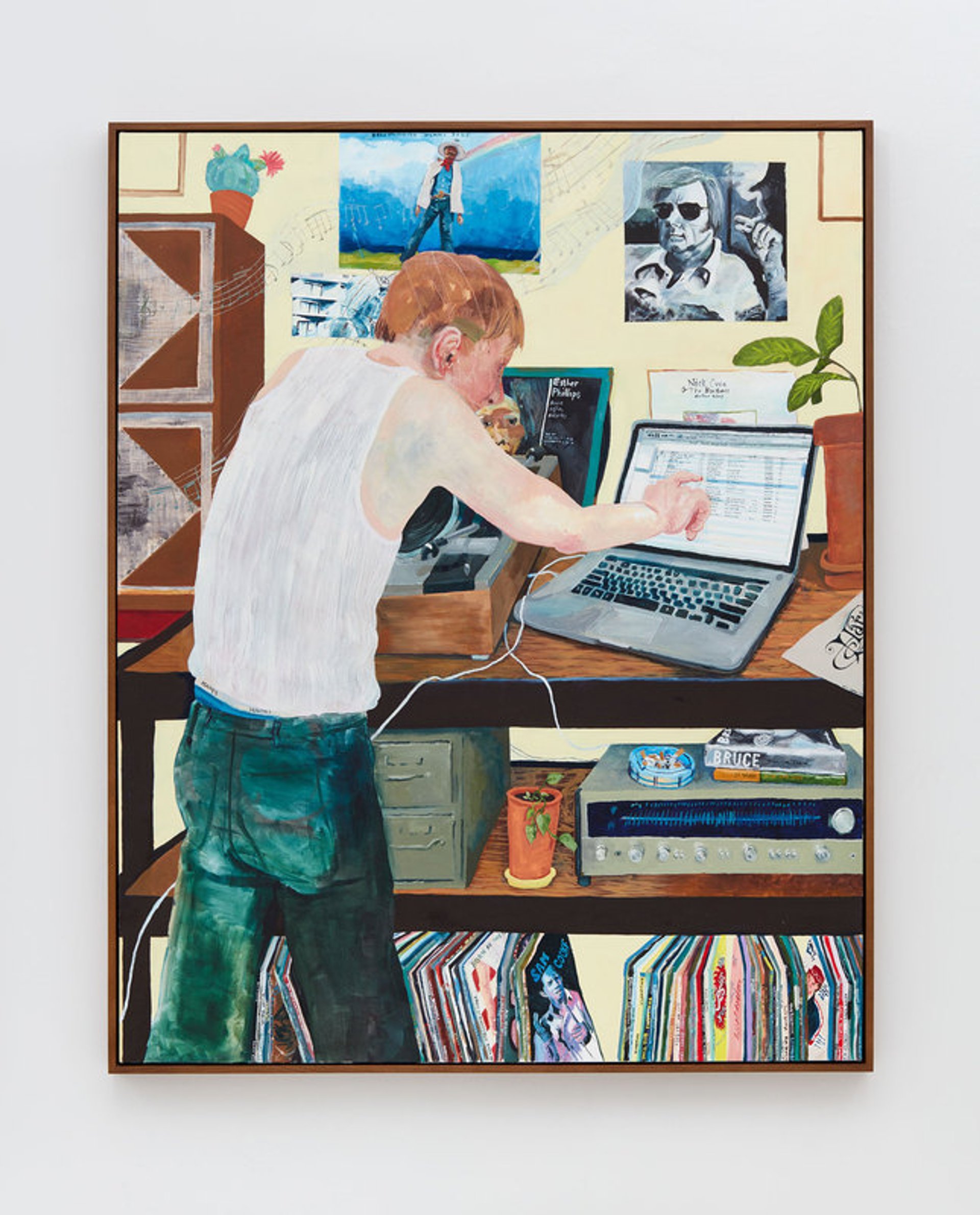

On the whole, the paintings included in this biennial seem especially out of sync with the stated focus on social crisis. Celeste Dupuy-Spencer is an incisive, able painter, but why include a watercolour picture of the basketball players Carmelo Anthony and Kevin Séraphin of the New York Knicks in a show about upheaval? Her images of happy Trump supporters at a rally, of the white supremacist and murderer Dylann Roof and of an anonymous brawl in Louisiana’s St Tammany Parish make more sense.

Henry Taylor’s work is especially strong, but there should be more of it; five pictures is not enough to get a sense of his talents. It’s fantastic to see so many paintings by Dana Schutz, like Elevator (2017)—the first thing most viewers will see when they exit the elevators on the fifth floor. It’s an enormous picture of discord, 12 by 15 ft, with arms and legs carved out of space. The same dissonance can be found with Lyle Ashton Harris, whose memoir in videos and slide projections, Once (Now) Again, is smart and truthful. It breaks the narrative into pieces, re-arranges the shards and makes a whole new picture.

Since it opened in 1932, the Whitney Biennial has always been a marker, a broad snapshot of the American moment, whatever that might be. This edition is no different and Locks and Lew succeed in their first goal. It is important, too, that they have included so many artists from the larger community not just the gallery regulars. This biennial presents the working artists of the day and they deserve the space to speak.

But it is no longer enough to say “crisis” when conditions darken. We have to ask: what kind of crisis? A brief ailment or a true disease? Can art do anything for it? What forms might that take? Where should our energy go? At the Whitney, the artist Porpentine Charity Hardscape has installed a text-heavy, choose-your-own adventure game you play at a computer. It is a simplistic presentation, but at least it begs the question.

• The Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 17 March-11 June