Hans Ulrich Obrist, the director of international projects at the Serpentine Gallery, contributes a characteristically thought-provoking foreword to this careful analysis of modern Middle Eastern art, Signs of our Times: from Calligraphy to Calligraffiti. Obrist’s own Instagram project, “The Art of Handwriting”, was an attempt to counter Umberto Eco’s fear that we are losing an art form in the replacement of handwriting by the typed and computerised word, and with it individuality and fluidity of expression.

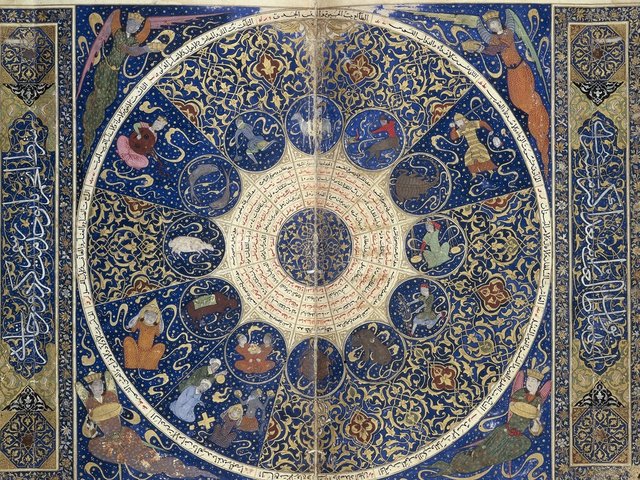

The Muslim world has long guarded calligraphy; indeed, it is the art form most characteristic of Islam, although, as Venetia Porter’s succinct contribution describes, the Koran conveyed by the angel Gabriel to the Prophet was not immediately written down but recorded by Mohammed’s followers on whatever material was handy—leaves, camel bones, etc—and collected together only later, in the mid-seventh century. It was as a vehicle for holy writ that the pre-Islamic Nabataean script used by the Arabs became refined over the centuries to the point where the written or engraved word has been identified as carrying the same immediate religious and cultural identification as the cross.

In The Image of the Word (1981), the Byzantinist scholar Erica Dodd compared the epigraphy of a mosque to Christian imagery. This significance could be independent of literal meaning: even where it would be physically impossible to read an inscription in the normal way, its very presence carried reassurance. It is hard to overstate the degree of respect accorded to the physical entity of any Koran, inscribed or printed, even today. In the minds of the unlearned, this came to embrace all forms of script and print: any scrap of writing might have a sacred connotation and be placed inside an amulet for protection.

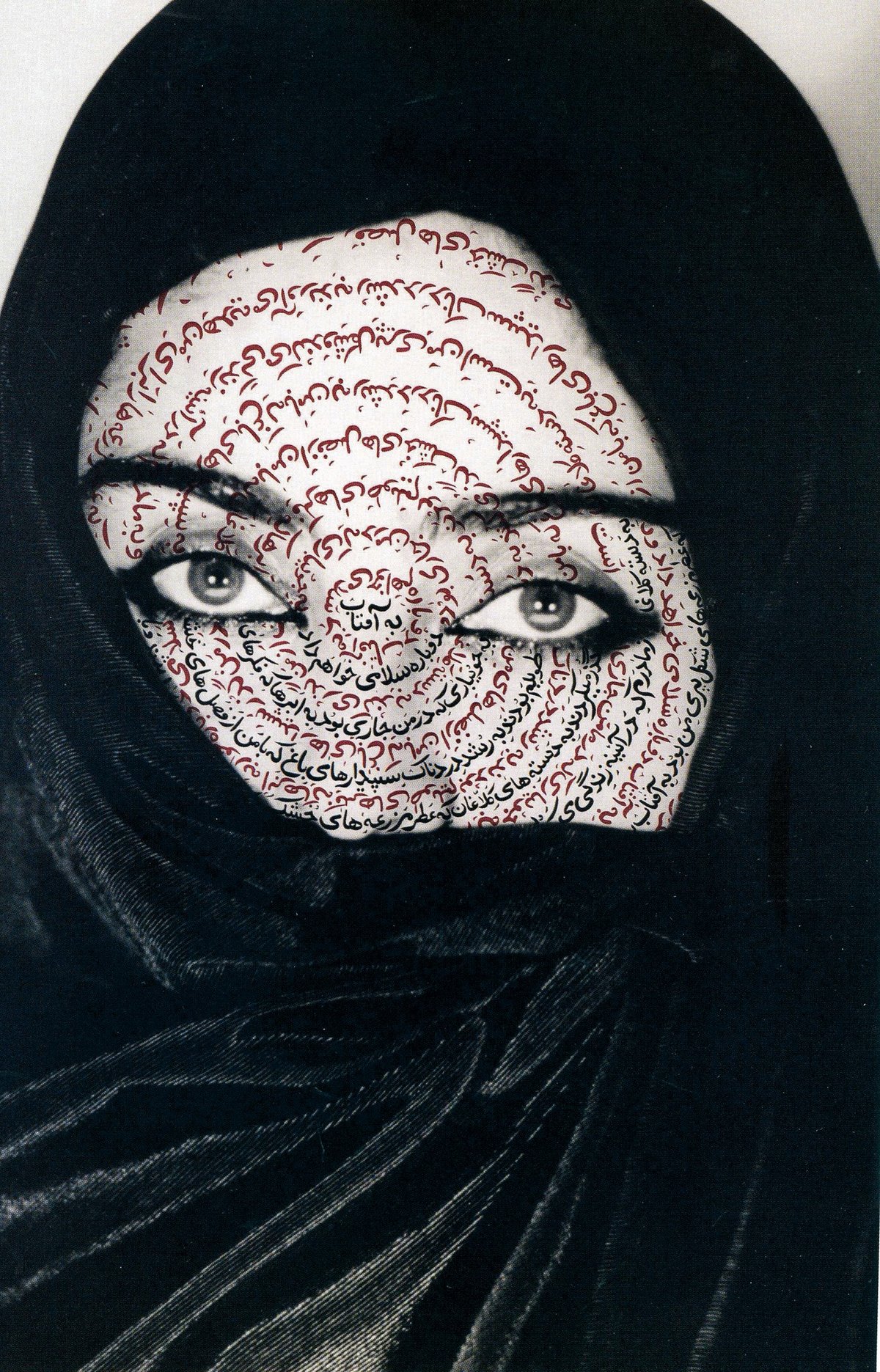

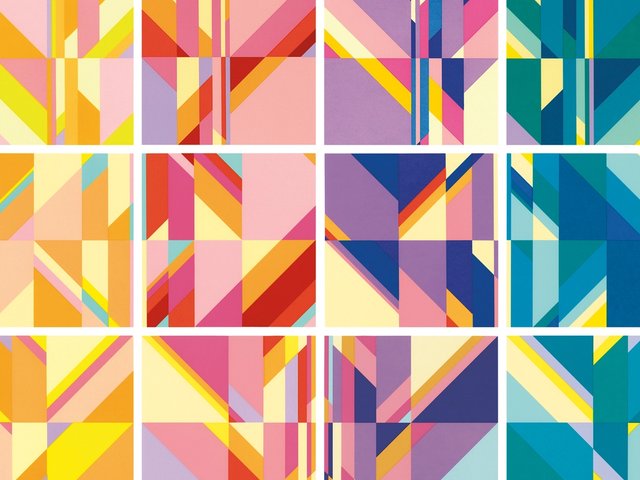

Though the formal Koranic scripts were undoubtedly beautiful, they required elaborate training to execute. The personality and freedom perceived by Eco in handwriting would not have been desirable aspirations for a Koranic scribe. But artists seeking new horizons began to incorporate script in work influenced by Western art. And script became a political weapon, now in the form of “calligraffiti” on walls and posters, especially in beleaguered Palestine. It might be noted that the lettering in Modern art is not usually drawn from classical script but from ordinary, everyday writing or print, still the hallmark of Islamic presence. Further, some artists have regarded “the word” not as liberating but as an instrument of control, witness Shirin Neshat’s Speechless, where a woman’s face is covered with narrow lines of fine script. The changes were outlined in Word into Art, a landmark exhibition (2006) at the British Museum organised by Venetia Porter and Rose Issa, doyenne of modern Middle Eastern art, who have developed it further in this collection illustrating the work of more than 40 artists and including these artists’ answers to intelligent questions about their work. Some of these are highly significant, for example the Palestinian artist Kamal Boullata’s illuminating response: “The recollection of how the linear aesthetics of Arabic calligraphy laid the foundation for all abstraction in Islamic art incited me to dig into this supreme expression in the history of Arab art.”

Some pieces illustrated here, such as Parviz Tanavoli’s Heech, a powerful sculpture turning the letters forming the Persian word for “nothing” into a creature struggling out of a cage, are well-known in the West. Heech was conceived as a protest against Guantánamo, and its international acceptance may now be militating against its power of protest, as is so often the fate of revolutionary art when rich collectors pounce. Other works will be new to most readers, but well worth the examination: I noted particularly the art of eL Seed, a street artist who began work at the start of the Tunisian revolution and whose giant wall graffiti incorporate the formalism of calligraphy. Issa’s subtle examination of the processes of change traces developments from the 1950s to the present day, when, sadly, most of the artists are émigrés. A process she defines as “circumnavigation”, following 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq, has led to the creation of new museums and centres of culture in the Gulf, and here she asks the pertinent question: “Who, exactly, is the audience?”

Yes, indeed, and how will the processes of destruction, inspiration and diaspora continue? Will the torch-bearers of Middle Eastern culture survive only in the West? This book provokes many questions.

• Jane Jakeman has a doctorate in Islamic art and architectural history from St John’s College, the University of Oxford. She has lectured on Islamic art, has been on the staff of the Bodleian and Ashmolean libraries and was librarian to the Oxford English Dictionary

Signs of our Times: from Calligraphy to Calligraffiti

Rose Issa, Juliet Cestar and Venetia Porter

Merrell, 320pp, £40, $70 (hb)