Next month marks 100 years since the abdication of the last Russian czar. Within months, Lenin and the Bolsheviks had seized power, shaking the world. In the wake of the takeover, the Russian avant-garde developed new forms of Modernism, which are the subjects of three major exhibitions in New York and London. Here, we take a look at the history of Russian Constructivism.

“Construction is the goal”

On 8 November 1920, the third anniversary of the October Revolution in Russia that ushered in the Bolshevik regime, the sculptor Vladimir Tatlin unveiled a model for his Monument to the Third International in Petrograd. The wooden structure, which stood around 20 ft. high, was at that point only a dream; it was a meagre fraction of the 1,300-ft.-tall structure of glass and steel the artist actually imagined. The finished work, intended to house the Comintern (the international Communist organisation tasked with proselytising for Marxism worldwide), would not just be more than a third taller than the Eiffel Tower; its four layered sections would also rotate continuously at varying speeds to illustrate the dynamism of Soviet Marxism. The tower’s spirals, the critic Nikolai Punin wrote, “are full of movement, aspiration and speed: they are taut like the creative will and like a muscle tensed with a hammer”.

Punin had got ahead of himself; the model in Petrograd was immobile and the project never developed beyond its initial phase. But “the birth of Constructivism came as a direct response to Vladimir Tatlin’s model”, the art historian Yve-Alain Bois wrote in an essay on the movement. In retrospect, it is clear why: Tatlin’s tower married utopian aspiration to utilitarian ideals, but in the end realised neither. By itself, this is a neat summary of Constructivism.

The ethos of the movement emerged amid a debate at the Bolshevik Institute for Artistic Culture (INKhUK). There, on 1 January 1921, the sculptor Aleksandr Rodchenko gathered a group of artists into a working group to discuss art’s role in the unfolding revolution. The members were in agreement on their opposition to INKhUK’s director, Wassily Kandinsky, whose pictures were too “bourgeois” in their good taste. They saw his paintings as expressions of his personal vision, for which there was no room in revolutionary times. “Down with Kandinsky! Down!” Punin wrote in 1919. “Everything in his art is accidental and individualistic.” Polemics such as these brought a swift end to his tenure: in January 1921, Kandinsky resigned his directorship.

Yet the key question remained: how was art to move past the “easelism’’ of personal expression? How was it to become useful for the revolution? For four months, over a group of drawings (each artist in the working group presented two), they argued bitterly among themselves and arrived, finally, at a simple conclusion: only art built on construction would do. From now on, individual composition would be jettisoned in favour of art built by, and for, a society that would develop according the principles of scientific socialism.

“Construction is the goal, the necessity and the purpose of organisation,” the artists Lyubov Popova and Varvara Bubnova wrote around 1920, and such construction was to make the artist anonymous. “No excess materials or elements”—no decoration, no signature flourishes—would be allowed; only what was necessary would be permitted. Constructivism emerged from the heat of these principles.

Art to make man active

Even in the early 1920s, when the movement was in its most productive theoretical phase, the project was under strain. The government support Tatlin enjoyed when his tower was commissioned by the People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment quickly dried up. Officials had bigger problems: the economy was staggering toward collapse and the New Economic Policy implemented in 1921 to revive it had reintroduced free-market elements into the economy. Artists were no longer guaranteed funding, and those who completed the shift from studio art to utilitarian construction found the work gruelling and unrewarding.

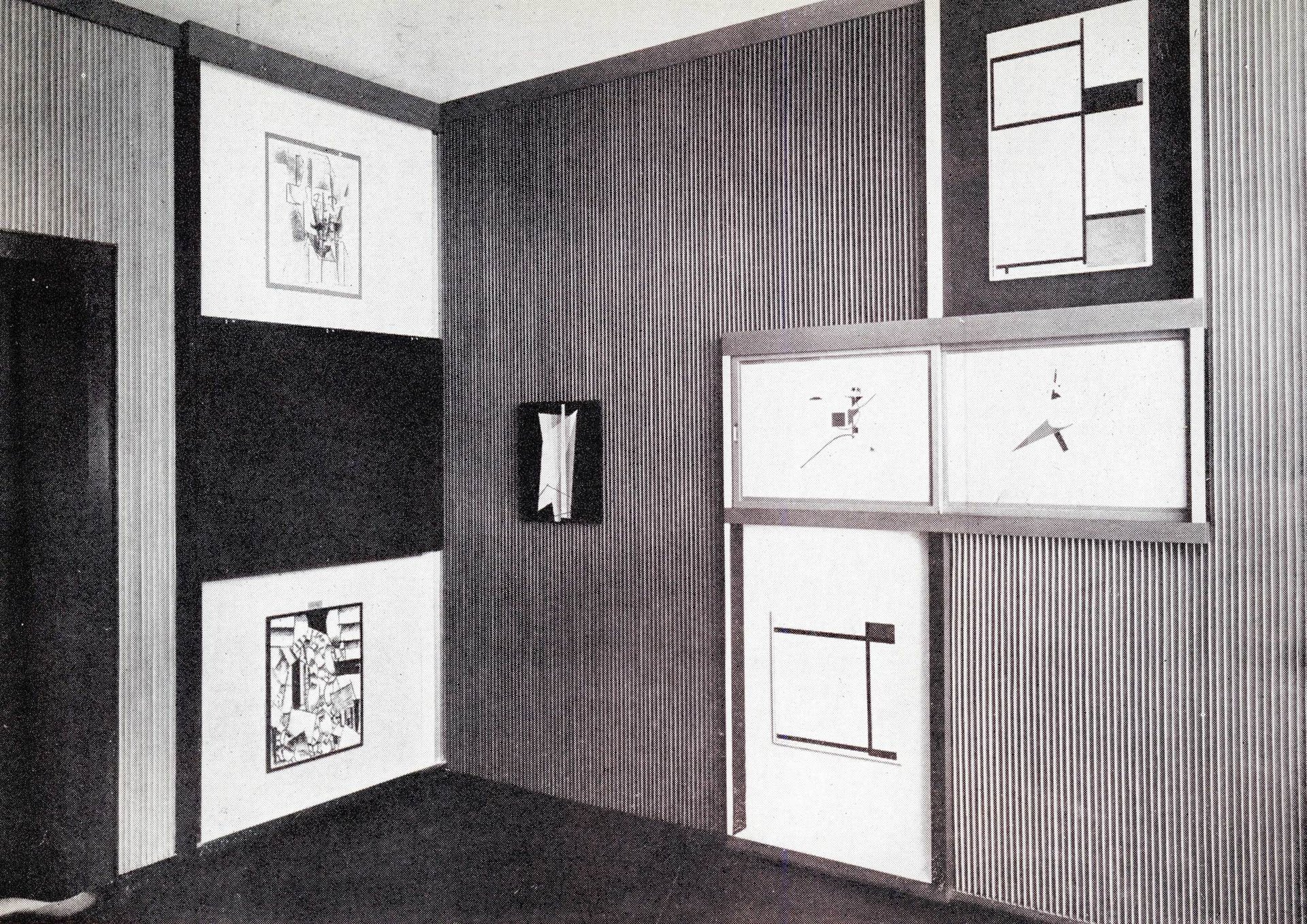

Yet in some ways, the art developed in its intended direction and became even more radical. Beyond the debates at INKhUK, El Lissitzky (a sometime member of the core Constructivist group) was experimenting with ideas for involving audiences in his work. “Traditionally, the viewer has been lulled into passivity by the paintings on walls,” he wrote in 1920. “Our construction/design shall make the man active.”

In Hannover in 1927, he presented what he considered to be one of his most important works: a Demonstration Room that included paintings by Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg and Mies van der Rohe hung asymmetrically to Lissitzky’s liking. Alongside the paintings were cabinets and drawers filled with objects, which viewers were invited to move and open on their own. The installation not only forced a new way of looking at Modern painting, it also imagined a new kind of museum.

Radicalism like this, which did away with the Romantic ideal of the lone, creative artist, made a deep impression on Alfred Barr, later the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, who made a visit to the Soviet Union in 1927. “I must find some painters,” he wrote in a letter to his wife, but the task proved difficult. Indeed, Barr found it hard to find anyone interested in Modernism as he understood it. Seeking advice from the writer Sergei Tretyakov, Barr noted that “he seemed to have lost all interest in everything that did not conform to his objective, descriptive, self-styed journalistic ideal of art”.

Yet by the time of Barr’s visit, the Modernist phase of Russian art was coming to an end. On 23 April 1932, the Central Committee of the Communist Party issued a decree that summarily disbanded all cultural institutions and regrouped them under a new umbrella administration. “Alien elements”, according to the text, had contaminated Russian art and literature, cultivating an “elitist withdrawal and loss of contact with the political tasks of the present”. Henceforth, experimentation was to come to a halt and Socialist Realism was inaugurated as the only sanctioned style.

In different ways, Constructivism lingered on, but never with the same utopian or utilitarian motivation. In Italy in the 1930s, the Rationalist architect Giuseppe Terragni even used some of its forms to build Benito Mussolini’s Fascist state. Here, the movement was turned against itself. But even this did not last. Like any revolution, in the historian Crane Brinton’s words, Constructivism rose like a fever that peaked and then diminished, leaving the patient “in some respects actually strengthened by the experience” but “certainly not made wholly over into a new man”.

For more, read what three experts have to say about the Russian avant-garde—and its collapse.