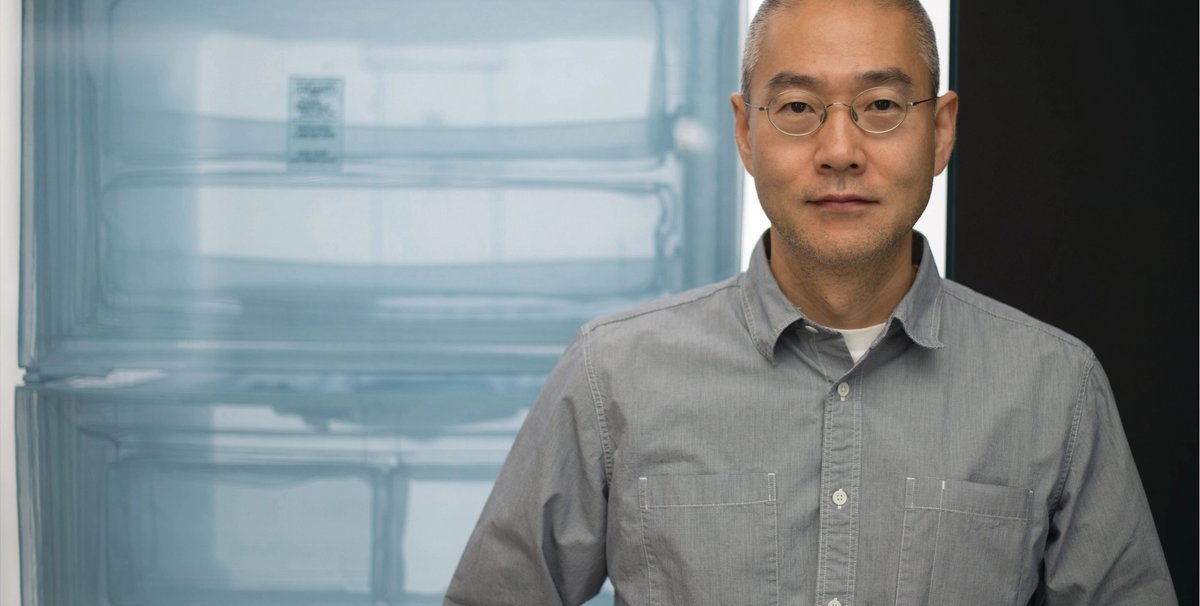

The South Korean artist Do Ho Suh, whose solo exhibition at Victoria Miro gallery in London opens tomorrow (Passage/s, 1 February-18 March), has created a unique memorial to his former apartment and studio in Chelsea in New York—which he occupied for almost 20 years—by rubbing every surface of the spaces with coloured pencils and pastels on to white paper. Suh has catalogued every sheet and aims to reconstruct the New York interior in the next few years. “The plan is for visitors to enter the reconstruction as if they were entering the apartment,” Suh says.

The artist moved to the four-storey New York residence on West 22nd Street in 1995. He had to give up the space in November last year after his landlord died. He began rubbing the interior around three years ago with the landlord’s permission; the brownstone residence has since been sold.

“The project is about memory and my time in that space. Rubbing reveals textures and marks, which are linked to my recollections,” Suh says, adding that the new owners may well change the layout of the property, making the piece even more potent.

Suh, who represented Korea at the 2001 Venice Biennale, began rubbing the ground floor and basement of the apartment, known as the “blue room”, where he rented his apartment from 1995 to 2010. His studio, which he occupied from 2010 to 2016 (the “yellow room”), was also on this floor along with the so-called “pink” corridor. The blue, yellow and pink spaces were rubbed with colour pencils while the rest of the house, including the staircases, were rubbed with pastels.

The project also entailed venturing into the private quarters of the landlords, Arthur and Dee Henoch, who lived on the floors above. Seeing this space, which was previously out of bounds, gave the initiative fresh impetus. “Making contact with the couple became a spiritual quest,” he says. “The work is a testament to Arthur and Dee [Arthur died last year].”

The project also tested him physically. Suh worked alone on the blue room rubbing, but enlisted assistants for the other areas. “With the coloured pencils, there is a distance between you and the surface, perhaps a matter of inches, but the pastels touch the surfaces. My fingertips touched every part, and were rubbed away,” he says. The paper impressions have since been transported to Suh’s studio in Brooklyn, where they have been archived. The artist stresses that the pieces will “take another couple of years” to put together.

This is not his first piece in this particular medium; at the Gwangju Bienniale in 2012, the artist showed three rubbings of spaces located around the Korean city. But he points out that the rubbing process began when he traced the outlines of parts of the apartment, such as the radiators, for his fabric pieces modelled on his domestic and work spaces begun in the late 1990s.

These translucent sculptures replicate the architecture of his past dwellings—including his abodes in Seoul, Berlin and the Chelsea residence in New York—giving shape to the artist’s peripatetic existence. He is now based in London. “I see life as a movement through many different spaces,” he says.

An exhibition of works at Lehmann Maupin in Hong Kong in March caps a peak period for Suh (20 March-13 May). The show includes small-scale drawings and centres on a three-channel film capturing the sights and sounds of the streets around the artist’s home in London.

The footage was shot on three cameras attached to his daughter’s pushchair. “The film shows us always on the move, capturing our travels over two and a half years,” he says. “It’s our journey together—we speak and sing in Korean and English.”