In 2006, the late painter Kenneth Noland started what would turn out to be his final series. The 15 works, created when the US artist was in his mid-80s, have never been shown publicly before. Next month, they will make their debut at Pace Gallery’s 57th Street location in New York (Kenneth Noland: The Last Paintings, 26 January-4 March 2017). Douglas Baxter, the gallery’s president, calls the series “a radical departure”.

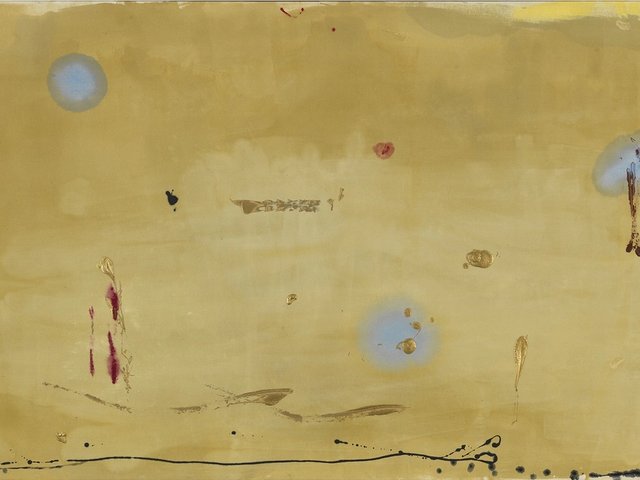

Noland—who became famous in the late 1960s for his brightly coloured concentric circles and shaped canvases—created the works at his studio in Port Clyde, Maine, where they have remained for the past decade. The palette and style were unlike anything he had ever done before: Noland applied pastel-coloured paint lightly, often leaving behind just a whisper of his trademark circle on the surface of the canvas.

“The amazing thing is that these were not shown in his lifetime and hadn’t been shown even afterward,” Baxter says. (Noland died in 2010.) “And here it is: a discrete body of work. In a way, it’s like he’s still alive.”

According to Baxter, Paige Rense Noland, the artist’s widow, always wanted to show these final paintings. But the project fell through the cracks immediately after his death, as the artist’s estate bounced between galleries before landing at Pace in 2013. The show is due to include around 10 paintings, but all 15 will be reproduced in the exhibition’s catalogue.

The art historian William Agee describes the series in a catalogue essay as “old age art” (work made shortly before an artist’s death), which he calls a “fascinating and still little-explored topic”. He writes: “If colour bands in Noland’s art had once seemed controlled and disciplined, these last paintings bespeak an artist letting colour loose, to fend for itself, to go where it might, with the artist no longer controlling so much as looking on with happy appreciation and pleasure.”

Of course, interest in “old age art” is not always purely academic. Many attribute the spike in attention paid to late work by artists such as de Kooning and Picasso more to market forces than art historical revisionism. (When the best known work by an artist is no longer available, dealers must turn their attention elsewhere.) But Baxter believes Noland’s final paintings will be judged on their own merits. “In the end, work is meaningful or it’s not,” he says.

For Baxter, Noland’s late works carry additional weight because the artist—who was considered by many to be among the strongest painters of his generation—was losing his eyesight at the time. “Noland was an extremely gifted painter and at that point in his career, he was very accomplished,” he says. Baxter has “a theory—mind you, it’s only a theory” about what Noland was trying to do as his vision was failing him. “He was trying to show people what he saw.”