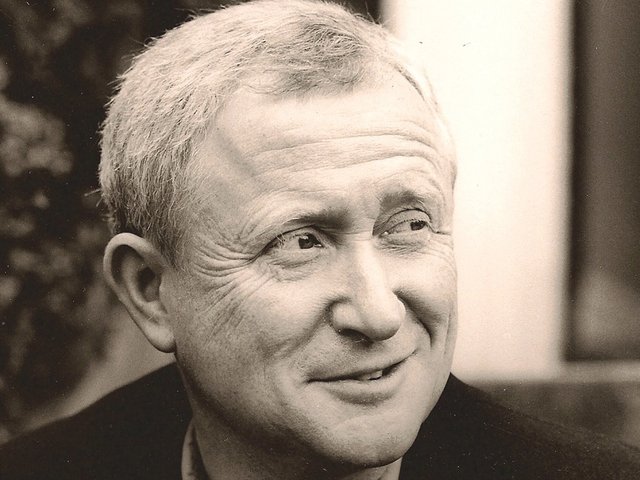

Giles Waterfield, who died on 5 November, aged 67, was the champion of the struggling museum. As the director of Dulwich Picture Gallery in south London (1979-96), he pioneered most of the now-familiar methods required to keep an economically unviable institution afloat; he grew the Friends organisation, scrounged from local schools, initiated an exhibition programme and managed to package every activity, however core, as a fundraising opportunity. His “Adopt an Old Master” scheme (based on animal adoption at zoos) proved that even conservation could be sold to donors. He further ensured that however empty the coffers and overworked the staff, the gallery offered groundbreaking education programmes to local schools free of charge, managed by Gillian Wolfe, and all (of course) externally funded.

In 1994 Waterfield exploited Sir Robin Butler’s review of the parent organisation, the Dulwich Estate, to announce that “England’s oldest public art gallery” would have to close its doors unless some alternative funding model was found. Later that year he successfully steered the gallery into that alternative: independent trust status, with a board chaired by Lord Sainsbury of Preston Candover. By the time Waterfield left Dulwich Picture Gallery in 1996 its future was secure. For the remainder of his varied career Waterfield kept returning to this central mission: to understand the artistic institutions created through 19th-century philanthropy and to make them work in 21st-century Britain.

Waterfield was educated at Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford, where he read English. An MA from the Courtauld Institute launched his curatorial career, his first job being as education officer at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton. His literary bent was evidently fed to excess by his experiences at Dulwich. Satirical material was visited upon him—Rembrandt’s small portrait of Jacob de Gheyn III was stolen (and retrieved) no fewer than four times—and he responded by describing his directorship with more thought to entertaining his audience than to doing justice to his achievements.

Waterfield was already planning his first novel—The Long Afternoon—while at Dulwich; it was published in 2000 and won the McKitterick Prize. Though belonging to a familiar genre—the twilight of the rentier—the novel is original in voice, cleverly structured and generous in its sympathies. Based on his grandparents’ life, through and after the Great War, in a villa at Menton on the French Riviera, many aspects of Waterfield’s own life can be recognised in the mores it describes: the hospitality, cultivation, good manners and tendency to tease. At the same time the social exclusivity and genteel inactivity, however sympathetically treated, excites a kind of horror, which clearly informed Waterfield’s extraordinarily wide and diverse circle of friends and his energetic, tightly scheduled life. His next novel—The Hound in the Left-Hand Corner (2002)—is a single-day satirical romp through museum life and art-world egos, in which many portraits were recognised (though only one was intended by the author). If it did not settle the scores it certainly burned the boats. The Iron Necklace appeared after much revision in 2015 and deals with an Anglo-German family during the same era covered in The Long Afternoon.

The other work undertaken during these freelance years was driven by his overriding interest in heritage, in particular 19th-century museums, and its promotion. In 1995, through the Attingham Trust, he helped to set up and became the director of Royal Collection Studies; its annual summer school was brought to life for most delegates by Waterfield’s gossipy “brief lives” of kings and queens (often delivered on the bus). Also for the trust he produced the seminal report on the educational potential of country houses and historic sites: Opening Doors: Learning in the Historic Environment (2004). He taught curatorship at the Courtauld Institute and found another outlet for his unusual gifts as a challenging mentor and generous friend. He organised many exhibitions: some, like Art Treasures of England at the Royal Academy (1998), intended to promote regional museums; others, such as The Artist’s Studio at Compton Verney (2009), drawing heavily on their resources.

Waterfield was asked in 2007 to give the annual Paul Mellon Lectures at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, which prompted him to condense a lifetime of research into the history of British museums, which appeared as The People’s Galleries: Art Museums and Exhibitions in Britain, 1800-1914 (2015). In this extraordinary book Waterfield employs a slightly reined-in version of his novelist’s skills—lively prose, wide sympathies and eye for detail—to tell the story of worthy foundations in Preston and Warrington, defending them against metropolitan scorn and making an impassioned case for measures to secure their futures.

• A memorial service will be held on 11 January at 3pm at St Martin-in-the-Fields, Trafalgar Square, London WC2