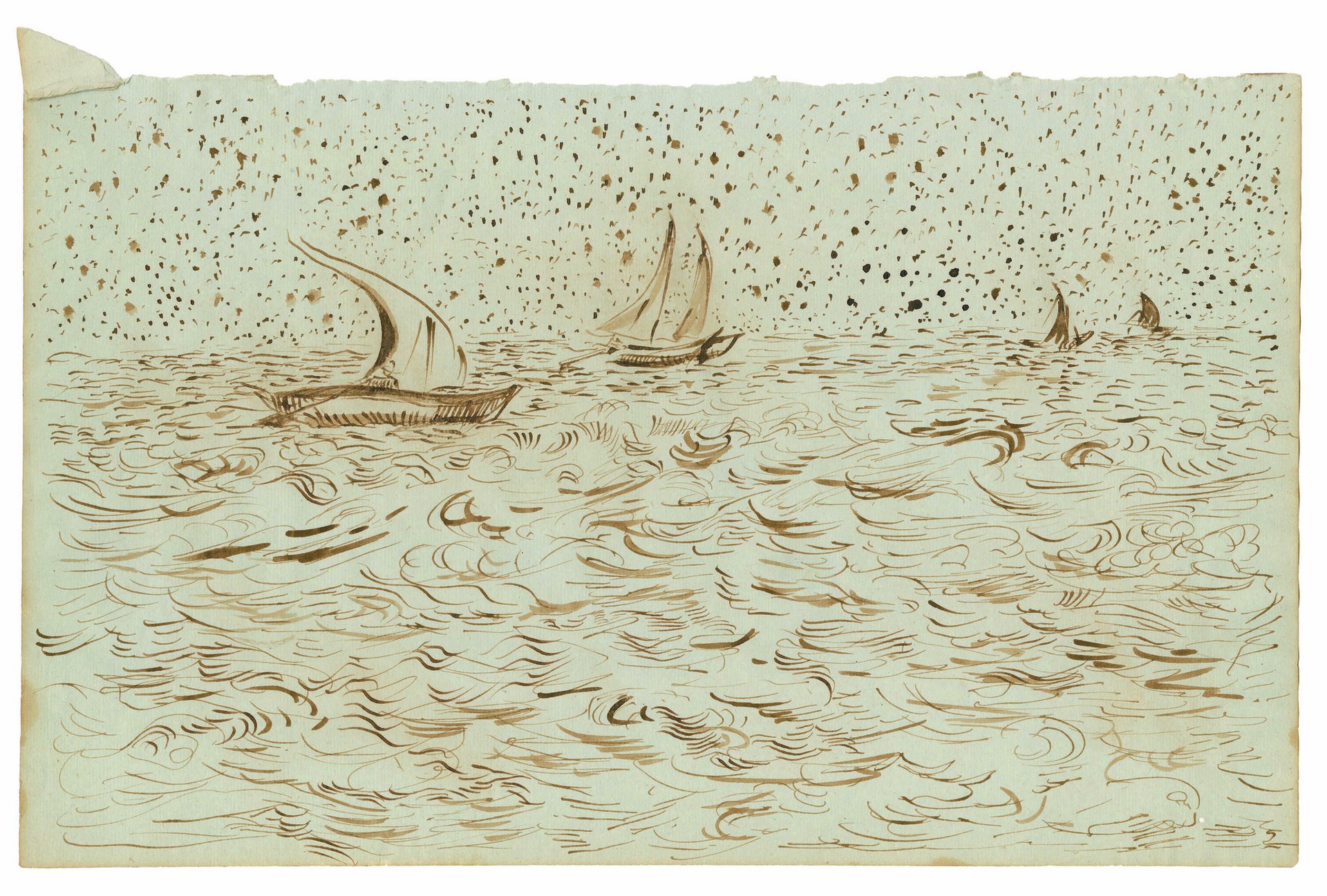

A set of 65 newly revealed Van Gogh drawings have been dismissed by the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam as “imitations”. They appear in a book, entitled Vincent van Gogh: the Lost Arles Sketchbook, to be published on Thursday 17 November.

Launched at a press conference in Paris on 15 November, the publication reproduces drawings that are said to be pages from a disbound sketchbook used by Van Gogh from May 1888, soon after his arrival in Arles, up until shortly before he left the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence two years later.

The book is by two well-established specialists. The author is the University of Toronto professor emeritus Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, and there is a foreword by the retired British academic Ronald Pickvance. The English edition is produced by New York-based Abrams, one of the world’s major art publishers, and is appearing simultaneously in French, Dutch and German.

Pickvance describes the sketchbook as “the most revolutionary discovery in the entire history of Van Gogh’s oeuvre”.

If the sketches are accepted as authentic, specialists will need to rethink the artist’s creative process in Provence. However, the Van Gogh Museum has taken the unprecedented step of issuing a detailed statement, concluding that the drawings are “not by Van Gogh”. If the museum is correct, the production of the 65 sketches (genuine works would sell for millions of pounds each) would be an audacious venture.

Louis van Tilborgh, the museum’s senior specialist on Van Gogh’s French period, told The Art Newspaper: “The style of the sketches is totally different from Van Gogh. The ink and the topographical mistakes in the drawings show that they were done by someone imitating Van Gogh’s work.”

The museum was initially approached in 2008 and 2012, when curators were shown photographs of 56 of the drawings, whose authenticity it then rejected. In 2013 the museum examined some of the originals, and came to a similar conclusion.

The museum’s statement points out that it is “very puzzling” that the drawings fail to reflect Van Gogh’s development as a draughtsman between 1888 and 1890. The brown ink in the sketches is accepted by Welsh-Ovcharov as being sepia shellac. In other fully accepted works in the museum and elsewhere, Van Gogh used black ink, which has often now faded to brown, so the maker of the sketchbook “must have been deliberately striving for brownish effects”.

According to the museum, there are also topographical errors in landscape drawings of the Langlois Bridge at Arles and the asylum building in Saint-Rémy. The museum concludes that “the maker and likewise the author of the book are not very familiar with the places depicted”.

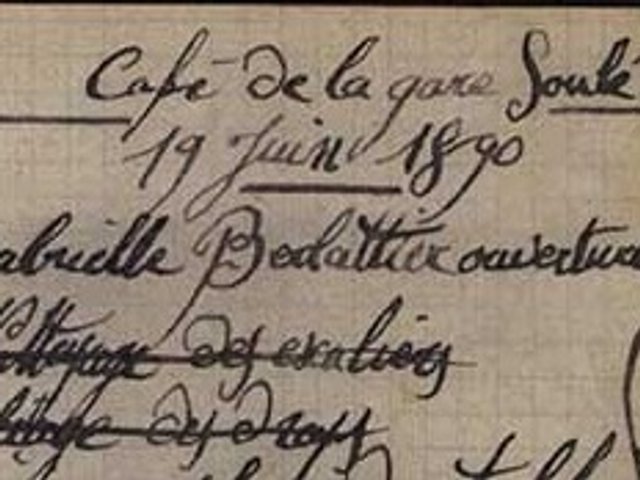

Welsh-Ovcharov says the provenance is backed up by an accompanying notebook. The museum says that its history is “highly improbable”.

Other questions about the provenance include why Van Gogh would give away two years of preparatory drawings to Marie Ginoux, a friend and café owner who seems to have had little interest in his work. And why did the present unnamed owner (who was brought up in Arles a few doors away from where Van Gogh had lived) receive the sketchbook as a gift in 1966 and not realise until only recently that three drawings depict the Yellow House and are loosely in the style of Van Gogh, who had done a famous painting of his home?

The public debate between the Van Gogh Museum and two highly experienced specialists (who both curated important exhibitions from the 1980s) looks set to divide scholars. But without the blessing of the Van Gogh Museum, the drawings are unlikely to be accepted by the art market.

Bernard Comment, the publisher of the French edition, says that he will be issuing a detailed response later today: “We have not changed our minds and are very happy that from now on everybody can make their own opinion, after seeing the drawings and reading the analysis in the book.”

• Martin Bailey is the author of the recently published Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln)