Fifty years ago, on 4 November 1966, Italy was hit by floods, devastating two of its most historic cities: Florence and Venice. This represented the greatest loss of art and architecture from a natural disaster in 20th-century Europe. The international community quickly mobilised assistance, dispatching angeli del fango (mud angels): volunteers who helped in the emergency rescue of works of art. “Everyone wanted to go and scrape mud off a Cimabue,” recalls Jonathan Keates, now chairman of Venice in Peril. Although most of the work on the ground was done by Italian conservators and volunteers, international efforts were important in providing funds and supplementary personnel.

Christopher Pirie-Gordon, the British consul in Florence, vividly described the flooding in a declassified dispatch at the National Archives. After exceptionally heavy and prolonged rain, the River Arno broke its banks, rising more than 10m above its normal level. Water quickly engulfed the Ponte Vecchio and swept through jewellers’ shops on the 14th-century bridge. Flooding extended throughout the city’s historic centre, reaching the cathedral and “doing incalculable damage to the Ghiberti doors of the baptistery”. The consul reported that cars were hurled into heaps, some “locked together upright on their back wheels as though engaged in a waltz”. This was the worst flood in Florence since 1557.

In his dispatch, Pirie-Gordon castigated the Italian authorities for not giving sufficient warning. He suggested that an alarm should have been sounded “in the historic form of tolling the great bell in the Palazzo Vecchio”. Emergency rescue work in the following days proves “lamentable”, and bureaucracy “clogs” the relief efforts.

Venice, 200km to the north, also suffered terribly, facing the worst flood in its history. Water levels rose on its canals, inundating the lower floors of buildings throughout the city. Sea water poured into the Palazzo Ducale (Doge’s Palace), the city’s greatest palace. Although the immediate damage in Florence was greater than in Venice, it was the latter that ended up attracting long-term international support for restoration.

Around 100 people were drowned in northern Italy, a mercifully modest number considering the huge area inundated. In financial terms, the initial cost of the disaster was estimated at between £500m and £1bn (around £9bn to £18bn in today’s money), according to the British chargé in Rome, Peter Scott. But for the art world, the tragedy was the extensive damage to two of the greatest cities of the Renaissance.

Since the floods came with little warning, there was little time to move works of art to safety. Thousands of paintings on panel and canvas were soaked by water, which was mixed with oil, sewage and dirt. Sculptures and frescoes were engulfed in the filthy water. Rare books and archives became waterlogged. The structures of historic buildings were threatened by the raging torrents. Museum buildings were badly damaged and in some cases took decades to reopen.

It is difficult to give meaningful statistics on the damage to works of art, since they obviously suffered to varying degrees and were of varying importance. Two months after the flood, 200 badly damaged panel paintings from various Florentine collections were being dried out in the Limonaia greenhouse in the Boboli Gardens. A further 300 canvases were being treated in the Palazzo Pitti. Figures compiled by Unesco a few weeks later suggested that 885 masterpieces and around 10,000 other works were damaged. At Florence’s Biblioteca Nazionale, 1.3 million books were damaged, a third of the collection. Precious archival documents were waterlogged. The art world was horrified.

The international effort to assist Florence was led by Ashley Clarke, a retired British ambassador in Rome. A month after the flood he set up the London-based Italian Art and Archives Rescue Fund, which was given office space at the National Gallery. (Its distinguished trustees included Anthony Blunt, Kenneth Clark, Philip Hendy, Henry Moore and John Pope-Hennessy.) By mid-1967 it had sent £100,000 to Italy, a substantial sum at the time. Virtually all this went to Florence, with only just over £1,000 specifically earmarked for Venice. A fundraising organsation was also set up in the US, as the Committee to Rescue Italian Art, with Jacqueline Kennedy as its honorary president. Similar groups were established in France, Austria, Germany and the Netherlands.

Two years after the floods, once the emergency work was complete, international attention switched from Florence to Venice. Frances Clarke, who with her husband Ashley was deeply involved, still vividly recalls what happened: “The Florentines said thank you, we can now cope; but the soprintendente from Venice pleaded: ‘You must come here.’” This led to the creation in 1971-72 of two fundraising bodies: Venice in Peril in the UK and Save Venice Inc in the US. Nearly 50 years on, they are still active, both in assisting in the preservation of art and architecture and in campaigning to help preserve the city’s delicate ecology.

Flood victims in Florence • Cimabue’s Crucifix (1280s) in Florence’s Museo dell’Opera at the Basilica of Santa Croce came to symbolise the destruction. Half its paint was lost, particularly on Christ’s head and chest. When this majestic picture was restored in the ten years after the flood, very extensive repainting of the lost areas was the only way for the work to regain its visual integrity.

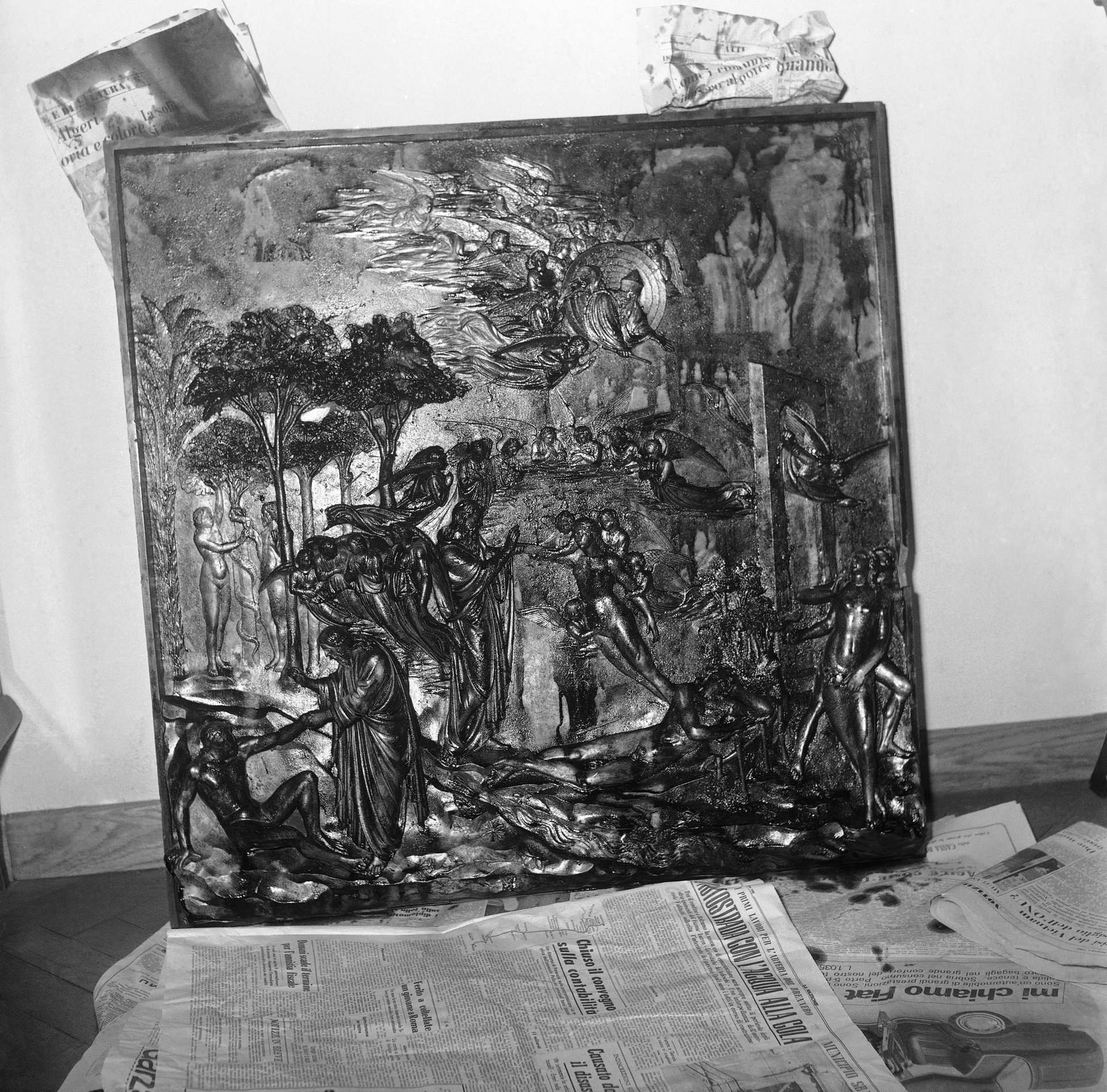

• Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise gilded-bronze doors (1426-52), on the exterior of Florence cathedral’s baptistery, were very badly damaged. Restoration of the north door was only completed in 2016. The originals are now on display in the new Museo del Duomo, with replicas installed in the baptistery.

• Giorgio Vasari’s Last Supper (1546) was in the Museo dell’Opera di Santa Croce when the flood waters rose. The 7m-wide picture, which had been immersed for 12 hours, separated into five panels. Conservation work, funded by the Getty Foundation, has recently been carried out by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure restoration laboratory in Florence. The completed restoration will be unveiled at Santa Croce on 4 November.