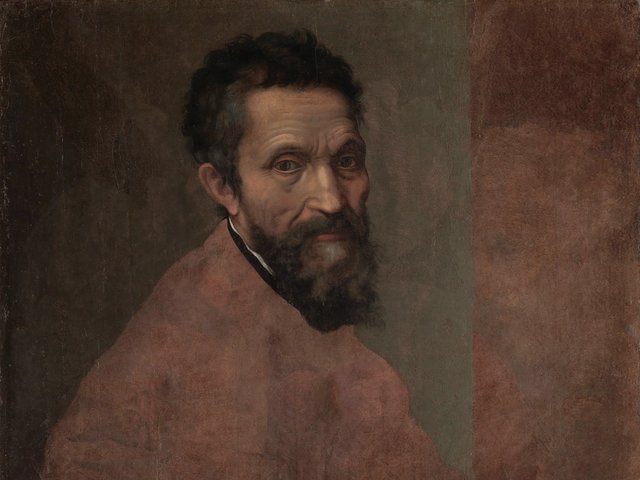

There can be few more flagrant instances of the law of unintended consequences than the way in which Vasari’s Lives of the Artists have all but fatally overshadowed his own artistic career. For while even his greatest admirers would concede that he was not a creative genius on the Olympian level of his hero, Michelangelo, he was an extremely accomplished painter and indeed architect. At the same time, it seems clear that—whether he would have agreed or not—the very best of him was reserved for his drawings.

Nevertheless, it has not hitherto been possible to appreciate the full extent of his achievement as a draughtsman. Florian Härb has been working on Vasari’s drawings for around a quarter of a century—his doctoral dissertation on the subject was completed in 1994—and some sceptics were beginning to wonder if he would ever give birth to this magnum opus. It is therefore an immense pleasure to report that it has been well worth the wait. There are two simple reasons why: the first is that Vasari finally emerges as a truly major draughtsman, and the second is that Härb writes about him with such understanding, authority and intelligence.

Like Gaul according to Julius Caesar, this mighty and immaculately produced volume is divided into three parts. The Drawings of Giorgio Vasari begins with a very substantial introduction—to which I will return —containing a sequence of more than 100 large-scale images of Vasari’s drawings, of which a mere handful are not reproduced in colour. The introduction is followed by the catalogue section, which runs to no fewer than 495 individual numbers, a few of which include supplementary drawings that are either by Vasari, and occasionally his associates, or are plausibly identified as copies of lost drawings by him. Even when the drawings in question are given what might be described as star billing in the introduction, they are unfailingly reproduced again on a smaller scale in the catalogue entries. What is more, where appropriate they are accompanied by copious illustrations of the works to which they relate. In consequence, it is invariably effortlessly easy to see how Vasari’s first —and indeed second—thoughts relate to his definitive solutions without having either to flip from the back of the book to the front or, worse yet, to surround oneself with a pile of other tomes.

In the nature of things, the number of absolute novelties within the 500 or so sheets assembled here is relatively few. But not only do they exist, more tellingly one or two of them are really significant additions to Vasari’s drawn oeuvre. It cannot be claimed, however, that of themselves they would by any means suffice to make this the game-changing publication it is. Where it really scores is in bringing together a record-breakingly scattered corpus between hard covers.

It is true that there are vast concentrations of drawings by Vasari in both the Uffizi and the Louvre, of which only the latter had previously been fully catalogued—by the great Catherine Monbeig Goguel, whom Härb acknowledges as the supreme trailblazer in this area—while for the rest even such major print rooms as those of London’s British Museum and the Albertina in Vienna can only boast 20 or so each.

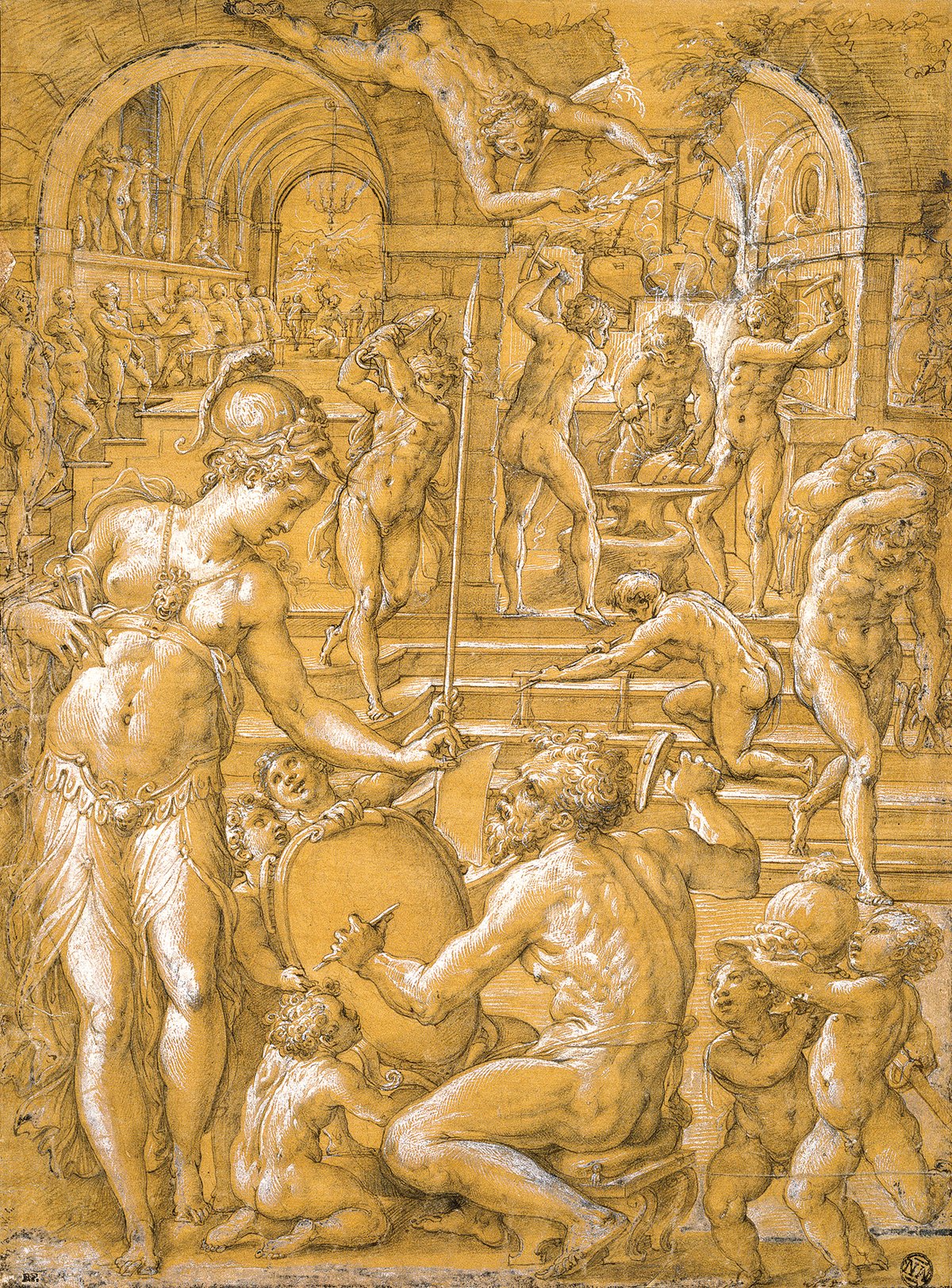

Elsewhere, more than 100 collections, both public and private (even Härb may not have seen either Abraham and the Three Angels (around 1571) in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires, Argentina, or the Allegory of Justice in the William Humphreys Art Gallery in Kimberley in South Africa, in the original) have anything between one and a dozen sheets by Härb’s hero in their care, and tracking them all down must have been a true labour of love. Moreover, when it comes to the colour plates, they underline both that Vasari was powerfully attracted to coloured grounds—above all blues, browns and yellows—and white heightening, but also the not unrelated fact that his most arresting drawings are almost invariably exceptionally highly finished. Conversely, anyone in search of the fine frenzy of inventive fervour that can often be communicated by Italian Renaissance drawings is likely to be disappointed by Vasari’s apparently cool and effortless manner.

Turning, finally, to the text, and above all the introduction, it eloquently conveys the extent to which—in his own words—Härb has been “infected with OMD, that highly contagious Old Master drawings virus, for which no cure has yet been found”. Wisely eschewing the straightforwardly chronological approach of the catalogue, the introduction is above all concerned with the relationship between Vasari’s theory of disegno and his artistic practice, which is further subdivided in terms of the various types of drawings he produced. Some of the categories, such as sketches (schizzi), compositional drawings, figure studies and cartoons are based upon function, while other groupings—and here the fundamental distinction is between finished drawings in pen and ink alone and those in pen and ink and wash, heightened with white—are based upon their technique.

Among many crucial insights, perhaps the most intriguing—not least for those of us more familiar with the artistic practice of the previous generation—is the extent to which Vasari in effect regarded drawing from the life as a species of training exercise for young artists that should ultimately no longer be necessary. As he puts it: “The best thing is to draw men and women from the nude and thus fix in the memory by constant exercise the muscles of the torso, back, legs, arms and knees, with the bones underneath. Then one may be sure that through much study attitudes in any position can be drawn by help of the imagination without one’s having the living forms in view.”

Vasari was of course also convinced of the vital importance of studying the art of the past, and Härb plausibly suggests that his desire to build up a visual archive may have been a major motivation—at least initially—behind his collecting of art. In this connection, especially in terms of his artistic borrowings, there is still work to be done. Thus, one of the figures in Härb’s no. 271 (The Liberation of San Secondo (1555)) is copied from an ancient statue of a Wounded Persian in the Vatican, while no. 303.3— which Härb gives to Jacopo Zucchi—is after Michelangelo’s Samson and Two Philistines (around 1550-55), and one could go on. That is as it should be, since all such projects are works in progress. No doubt a new Vasari drawing will emerge from someone’s attic or be found hiding under a wrong attribution in some obscure print room any day now, but Florian Härb can rest assured that nobody is remotely likely to surpass his work for the next century or two.

• David Ekserdjian is professor of art and film history at the University of Leicester. A world-renowned authority on Italian Renaissance art, he is the author of monographs published by Yale on Correggio (1997) and Parmigianino (2006). He organised the acclaimed exhibition Bronze (2012) at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (with Cecilia Treves), and his latest exhibition, Correggio and Parmigianino: Art in Parma during the 16th Century, took place at the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome

The Drawings of Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574)

Florian Härb

Ugo Bozzi Editore, 752pp, €240

(pb, boxed)