At the end of June, Robert Irwin put the finishing touches to his project at the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, the art complex founded by the artist Donald Judd on a former army base in western Texas. The first new permanent single-artist installation at the site in 16 years, Irwin’s project is due to be publicly unveiled on 23 July.

The 87-year-old California artist has been having something of a revival in recent years, with major exhibitions at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC and Dia: Beacon—but this was not always the case. “What I've been doing all these years, you couldn't sell, you couldn't house it, you couldn't put it in a museum,” Irwin told The Art Newspaper in June. “Marfa was a good place for me to fantasise some idea of what I might do, which for a long time was all I had… It was a nice place for me to stretch my legs a little and try some things.”

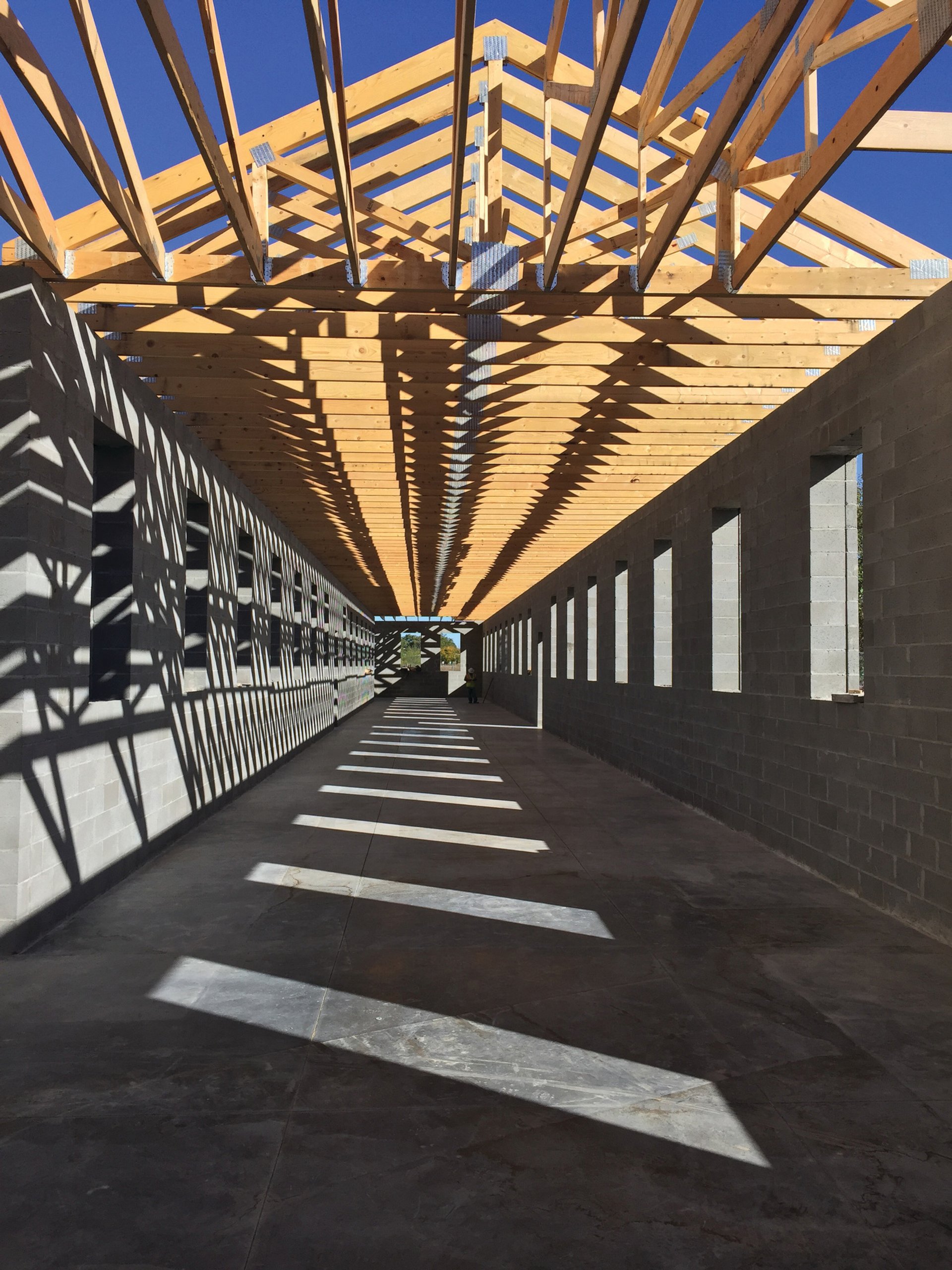

Irwin’s new work is on the site of a former hospital building that had fallen into disrepair. Like his Scrim Veil (1977, 2013) at the Whitney Museum in New York, the work plays with light and space. One half of the building is shadowed in darkness and the other is bright, with a transparent scrim separating the structure, and films on the window that manipulate the natural light.

Irwin revealed that he first visited Marfa when he was taking a road trip along the US border in 1971. He bumped into Judd, a friend, who told Irwin that he was “thinking of buying up the town”.

The artist talked to us about what it is like working in Marfa.

The Art Newspaper: This has been the culmination of 15 years. Why did it take so long?

Robert Irwin: Well one reason was it took a while to build Marfa up. This place was piss-poor for years. Marfa was just this place in the desert. If you wanted to get a bite to eat, you had to drive 26 miles to Alpine to get lunch or dinner, if you wanted to sleep [in a hotel] you had to drive 26 miles in a different director to Fort Davis, then you slept and you drove 26 miles back to Marfa, that's how much there was here. So the first question became: why Marfa?

Marfa was just flat out in the middle of nowhere, but actually there's something quite magical here. When you drive on Rt 10 and turn off at that point at Van Horn you have to swing on around to Marfa and something changes. It has to do with the quality of the sky here. It’s immediate, it's in your face. Skies are normally way up in the air where you don't really connect with them; you’re not really aware. The only other place I saw this was in Miami. The sky would come out of the swamp and race over the sea. It’s in your field of vision all the time.

Essentially that’s the rhyme and the reason of what I'm trying to do here. I wanted to work outside. Marianne [Stockebrand, Judd’s partner when he died] wanted me to work inside. I didn't want to because that's what you do when you're in New York, you don't do that in Marfa.

Do you remember when you first came out to Marfa?

I decided it was too cool in Los Angeles so I went to San Diego to be a little warmer, and I thought it might even be warmer if I moved over to Arizona. And I got hooked on the idea of following the border. At one point you get to Van Horn, and the border has moved away from you, and you get to Marfa, and turn down to Presidio.

At some point I ran into Don Judd and he said ‘I'm thinking of buying up the town.’ And I said, ‘No kidding.’

You guys were friends at that point?

Don Judd was the only guy in New York who befriended me. I met with the sculpture mafia and they all pooh-poohed me. And Judd said, ‘Oh, this guy's all right.’

Who was the sculpture mafia?

You know, Andre, not so much Le Witt, not Flavin, di Suvero, not Tony Smith, Richard Serra.

Did the magic you describe hit you the first time you saw Marfa?

It took a while. It becomes apparent that it's magical and that there are clouds are dancing over your head in a few places. I don't know exactly what the weather conditions are but there's something that holds the clouds down low and they race across this wild plane. Marfa has became a unique place.

Why do we need places like Marfa?

If you look at the art world, it's not an art model, it's not a creative model. It's an economic model. It's the idea that half the business is carried on in these art fairs which means the only things that can be shown are things that can be put up in a day, profitable, on a patched wall with temporary lighting. Modern art is much more interesting and more critical. It's a simplification, socially.

That's why Don Judd, his first impulse was to get the hell out of there. He didn't like what people did to his work, how it was seen, how it was understood. Marfa became a critique, out of his idea that the art world was broken. So he came out here.

And I agree with him. What I've been doing all these years, you couldn't sell, you couldn't house it, you couldn't put it in a museum. Marfa was a good place for me to fantasise some idea of what I might do, which for a long time was all I had. It was a nice place for me to stretch my legs a little and try some things.

So finally it's coming to a conclusion and hopefully it'll be good. I never know until the last minute really. That's why I'm here trying to fine-tune it continuously until we've got it as tight as we can make it. And I'm looking forward to it.