Visitors to Goethe’s house on the Frauenplan at Weimar pass through the Maiolica Room, where samples from his collection of Italian tin-glazed pottery are displayed. The Klassik Stiftung Weimar, which conserves and studies the heritage of Weimar Classicism, has now sponsored a beautifully produced new catalogue of Goethe’s maiolica. Since it contains large coloured illustrations of every one of the 105 items, along with detailed descriptions and accounts of their provenance, Italienische Majolika aus Goethes Besitz must be considered exceptional value for money.

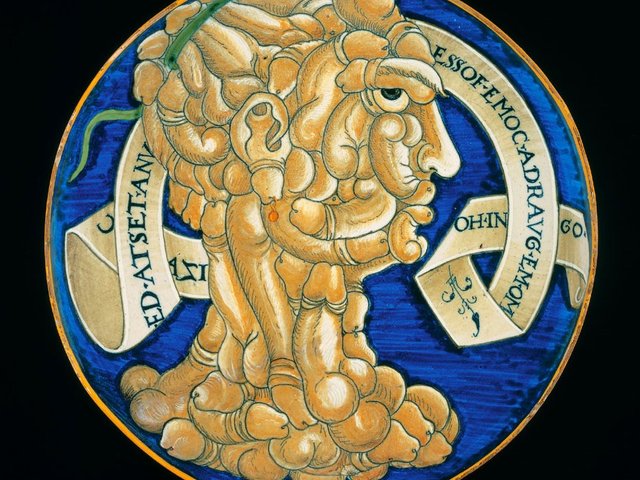

The introductory essay tells us about the production and sale of maiolica. Two-thirds of Goethe’s pieces come from Urbino, one of the great centres of istoriato pottery—that is, plates and the like with brightly coloured historical, mythological or Biblical scenes, which were particularly popular in the early and mid-16th century. Some of Goethe’s maiolica can be traced to specific workshops, including the two leading ones in Urbino, belonging to Guido di Merlino (active in the 1540s) and his rival Guido Fontana (last recorded in the 1570s). Most of the remaining items come from Venice, mainly from the workshop of Domenico da Venezia (documented from the 1560s). Surprisingly few come from Faenza, the great centre of maiolica production where the istoriato style originated soon after 1500. The collection also contains a few non-Italian items: three bowls from Germany, and some cups and salt cellars from Limoges.

In Germany, the trade in maiolica and other artefacts centred on Nuremberg. In the late Middle Ages Nuremberg, like Augsburg, was an important commercial city governed by patricians. The value they attached to art is apparent to anyone who visits the handsome four-storey house occupied by Albrecht Dürer. By the 18th century, however, Nuremberg had fallen on hard times, and many art collections had been offered for sale. When in Nuremberg in 1797, Goethe almost certainly visited the collection of Hans-Albrecht von Derschau, a Prussian officer whose poor health induced him to retire and devote himself to art. Early in 1817, after prolonged negotiations over the price, Goethe bought from Derschau 42 pieces of maiolica and three enamelled vessels. After Derschau’s death in 1824, his property was auctioned, and Goethe then acquired more pieces, notably a plate with a fine depiction of Scipio Africanus in Spain (no. 36 in the catalogue).

Why did Goethe collect maiolica? He was of course an enthusiastic collector of paintings, sculptures (including plaster casts of famous statues), drawings, porcelain, gems and much else. His collection numbers some 26,500 items, only a small proportion of which can be shown to tourists. But his interest in maiolica developed late. During his stay in Italy, from 1786 to 1788, he showed no interest in it. In a satirical epigram of 1797 he even mocked people who preferred maiolica to ancient vases. By 1804, however, he owned a few pieces, and from 1816 onwards he collected maiolica seriously.

It may not be coincidence that Goethe’s wife Christiane died in the summer of 1816. When his big purchase arrived from Nuremberg in February 1817, Goethe turned what had been the marital bedroom into the Maiolica Room. He spent a whole week arranging his new acquisitions, and had wooden cabinets made in which they could be displayed behind glass. This may be seen as valuable self-therapy for a grieving widower. But Goethe, though saddened, was not heartbroken by Christiane’s death. In the last few years of their marriage they had drifted somewhat apart, and Goethe had indulged a warm, romantic friendship with the young, pretty, gifted Marianne von Willemer.

Goethe’s maiolica provided light relief when his life was becoming increasingly sombre and difficult. As the catalogue lets us appreciate, the paintings are in cheerful colours, with lush green landscapes, dark blue rocks, seas and lakes, vivid orange robes for the figures, and orange curtains in domestic interiors. In a sense, too, maiolica gave relief from serious art. Malcolm Bull notes in The Mirror of the Gods (2005) that its artists “gravitated towards a more light-hearted and erotic subject-matter”. Goethe seems to have regarded maiolica as an indulgence; he never mentions it in his copious writings on art and he talked about it only with a few intimates. To one such, the composer Carl Friedrich Zelter, he wrote in 1827: “The presence of these dishes, plates and vessels gives an impression of cheerful practical life… You see how one can extenuate one’s follies, but praise to any folly that gives us such harmless enjoyment.”

The scenes painted on Goethe’s maiolica come from classical mythology, with Ovid’s Metamorphoses a popular source, as well as Roman history and the Bible. When in Italy, Goethe regretted that gifted painters had such repulsive subjects; he did not enjoy looking at aged monks and saints. But the maiolica pieces incur no such objection. The only saint here is the evangelist Mark, seated on a cloud and wrapped in a splendid blue robe (no. 68). The Last Supper takes place in public, at the top of a flight of stairs thronged with people (no. 35). Old Testament scenes are numerous: Joshua enthusiastically massacres the Amorites, the sun standing still to let him finish the job (no. 89); Moses’s enemies led by Korah plunge into an abyss while their tent goes up in flames (no. 88).

Naked bodies, love scenes and bold erotic episodes make us think again about Goethe’s marital bedroom. Eve, Venus, Diana, and the three goddesses subjected to the judgement of Paris, all display their charms (though the two unsuccessful contestants give Paris very dirty looks: no. 13). Jupiter’s dealings with Io (no. 69) and Leda (no. 9) leave nothing to the imagination. More curiously still, Callisto is embraced by Jupiter disguised as a woman (no. 22).

The piece with the clearest link to Goethe’s poetic imagination must be no. 26, showing the triumph of the sea nymph Galatea. She stands on a shell, surrounded by amoretti, dolphins and a couple of ardent lovers on a raft. At the climax of the Classical Walpurgis Night in Faust, Part II, Galatea appears riding on a shell-chariot, attended by dolphins and symbolising the primal life-giving power of the sea. The maiolica paintings are certainly light-hearted—and all the more delightful for it—but it would not be surprising if one of them helped to inspired what Goethe called the “very serious jokes” of Faust II.

• Ritchie Robertson is the Taylor Professor of German at the University of Oxford. His most recent book is Goethe: a Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2016)

Italienische Majolika aus Goethes Besitz. Bestandskatalog

Johanna Lessmann, with contributions by Christiane Holm and Susanne Netzer

Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 360pp, £45/€49.80/$85 (hb)