The figures speak loud and clear, just as they did in New York in May. This time last year, the combined total for London’s Impressionist and Modern evening sales at Christie’s and Sotheby’s was £250.1m (including fees). This season the total has fallen by nearly 50% to £128.9m, just as it did in the New York sales.

Sotheby’s 27-lot sale fetched a £90.7m hammer total (£103.3m with fees) against an estimate of £81.8m-£99m. The 33 lots at Christie’s achieved £21.8m (£25.6m with fees), below the estimated £32.8m-£48.7m. In June 2015, the two auction houses’ equivalent sales had 50 lots each. Volume and value have halved, and buyers are extra picky.

During the past months, financial markets have remained weak, while the art market has suffered from a lack of big estates up for sale. With the general fog of uncertainty that covered the UK while the EU referendum debate raged on, finding art to sell was particularly tricky for both houses, notably Christie’s. The success of the Sotheby’s sale depended on two star lots: Picasso’s portrait of his lover Fernande Olivier, Femme assise (1909), and Amedeo Modigliani’s Jeanne Hébuterne (au foulard) (1919). These two works accounted for just under 80% of the evening’s total (£81.8m with fees). Without these, Sotheby’s total would have looked a lot more like Christie’s. What a difference two lots can make.

“Sotheby’s really turned it around since the New York sales [in which it notably underperformed compared with Christie’s],” says Thomas Seydoux, the art adviser and former international co-head of Impressionist and Modern at Christie’s. “But at the moment the market is not deep enough to sustain two sales: one is always weaker.”

Did Brexit vote ruin the party? While the UK had not yet voted to leave the EU, the possible negative effects of the referendum on 23 June were the topic of heated debate before and after the sales took place. Did it affect consignments? Did it dampen buyers’ spirits? While it certainly didn’t cause the art market’s contraction, it surely didn’t help.

Olivier Camu, the deputy chairman of Impressionist and Modern Art at Christie’s, says: “Its impact on currencies and economic growth was a constant presence in conversations with most clients leading up to the sale. The uncertainty and related insecurity were at their highest the night before the vote [the night of the Christie’s sale] and I did see some cancellations on the night.”

Jussi Pylkkanen, the president of Christie’s Europe, says that oil price fluctuations at the start of the year affected the auction house’s ability to secure great works.

The Impressionist and Modern category is also known to be tough on supply. With no great estates on the block, both houses had to make do with what was available. The only two star lots went to Sotheby’s, which had better works and better estimates.

“There were fewer sellers but there are buyers who still want real quality,” says James Mackie, the head of Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern department in London.

The post-Brexit fall in the value of the pound gives foreign collectors more purchasing power, and could even stimulate future sales.

Allure of curated sales Christie’s penchant for staging extracurricular—and very successful—curated sales across multiple departments often means star lots are cherry-picked from the regular evening sales, which are weakened as a result. The monumental Henry Moore sculpture Reclining Figure: Festival (1951), with a £15m-£20m estimate, would have changed the face of the Impressionist and Modern auction, but it was one of the leading lots in Christie’s 250th anniversary sale, Defining British Art. This sale’s total estimate is £97.6m-£140.1m—far higher than the Impressionist and Modern figure. As we went to press, the anniversary sale had yet to take place.

At the same time, the allure of a grand curated sale is precisely what helps draw works in the first place, Pylkkanen says. Sotheby’s by comparison was able to focus all its efforts on one evening sale, and came out on top partly as a result.

More than just a big name “Eighteen months ago, a big name was enough to sell a picture. Now you need a good subject, good dates and the right estimates,” Seydoux says.

A common characteristic of many of the top Christie’s lots that went unsold is that they were slightly, or in some cases noticeably, atypical. The Monet cover lot, L’Ancienne rue de la Chaussée, Argenteuil (est £4.5m-£6.5m), painted very early, in 1872, did not look like a traditional Monet. And Salvador Dalí’s large and very early work, El rec de La Jorneta (1923) (est £700,000-£1m), was unrecognisable as a Dalí. Picasso’s late Mousquetaire et fillette (1967) (est £2.8m-£4.8m), may have been easier to identify, but it simply was not the ‘right’ Picasso.

Over at Sotheby’s, Picasso’s Femme assise (1909) was the perfect bait for cautious collectors in search of a trophy buy. The Cubist work saw two bidders push the price up to £38.5m (£43.3 with fees), the highest paid at a London auction in more than five years.

Modigliani, however, was the star of the week. The familiar elongated necks and slender faces of his two sitters, Jeanne Hébuterne (au foulard) (1919) and Madame Hanka Zborowska (1917), meant both were sought after. The works sold above estimate for £34.3m (£38.5m with fees) and £7.3m (£8.3m with fees) at Sotheby’s and Christie’s respectively.

Auction results Impressionist and Modern

Sotheby’s, 21 June

Hammer: £90.7m

With fees: £103.3m

Estimate: £81.8m-£99m

Sold by lot: 89%

Lots: 27

Christie’s, 22 June

Hammer: £21.8m

With fees: £25.6m

Estimate: £32.8m-£48.7m

Sold by lot: 64%

Lots: 33

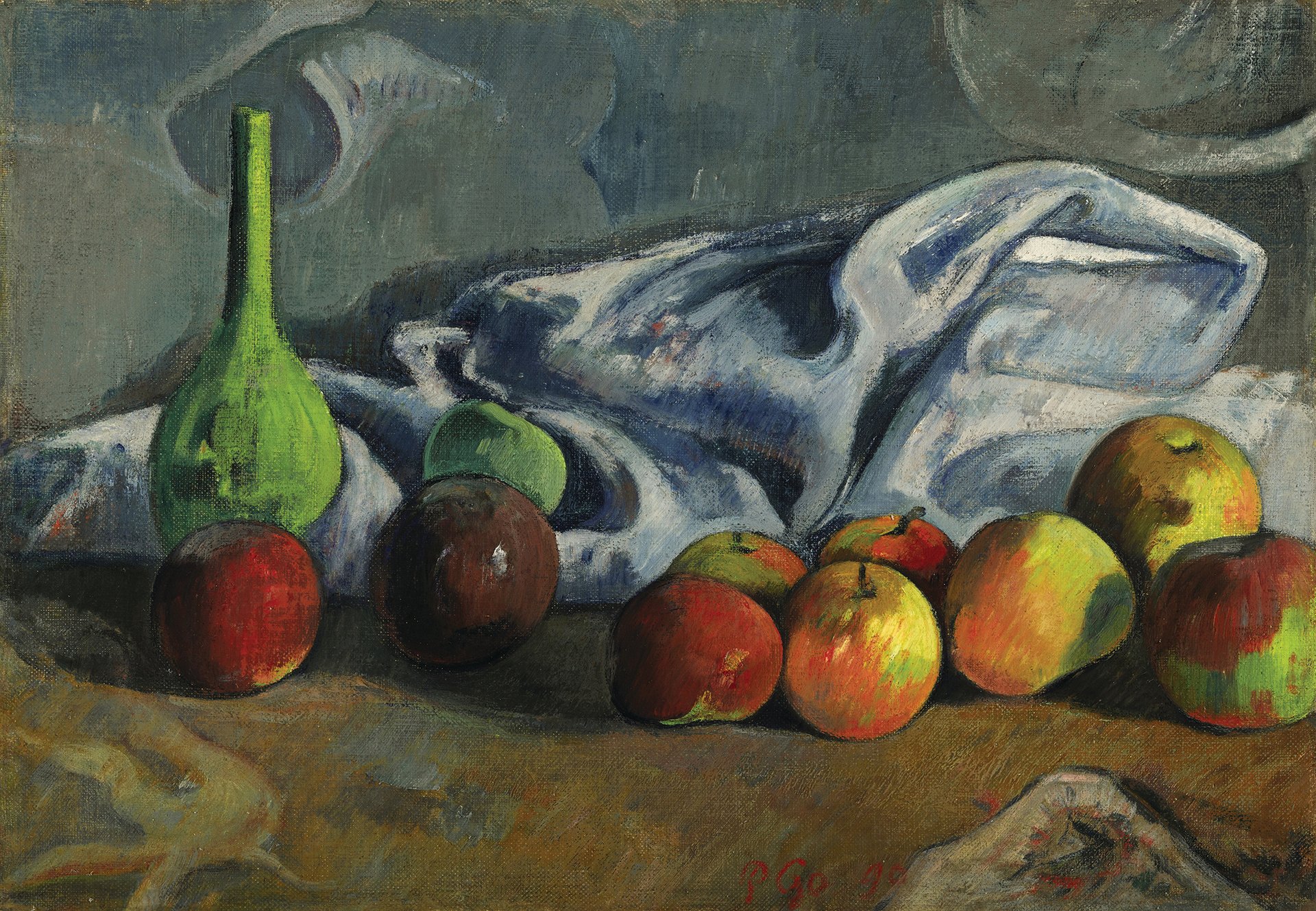

Story behind the sales Paul Gauguin, Nature morte aux pommes (1890)

Sold at Sotheby’s, 21 June, for £2.9m (£3.4m with fees; est £2.2m-£2.8m)

Painted in Brittany, shortly before Gauguin made his first trip to Tahiti, the work shows the profound effect that Cézanne’s work had on Gauguin’s own painterly style. Gauguin did, in fact, own at least one still-life painting by Cézanne. The crossover of two of the biggest Modern artists spurred collectors to push the price far above the estimate. It was eventually bought by a private American collector. This work fetched the third highest price of the evening at Sotheby’s, after the Picasso and Modigliani star lots. It had been off the market since 1980 and is to be included in the new edition of the Gauguin catalogue raisonné. “It has great wall power,” James Mackie says. “It’s small, but packs a huge punch.”

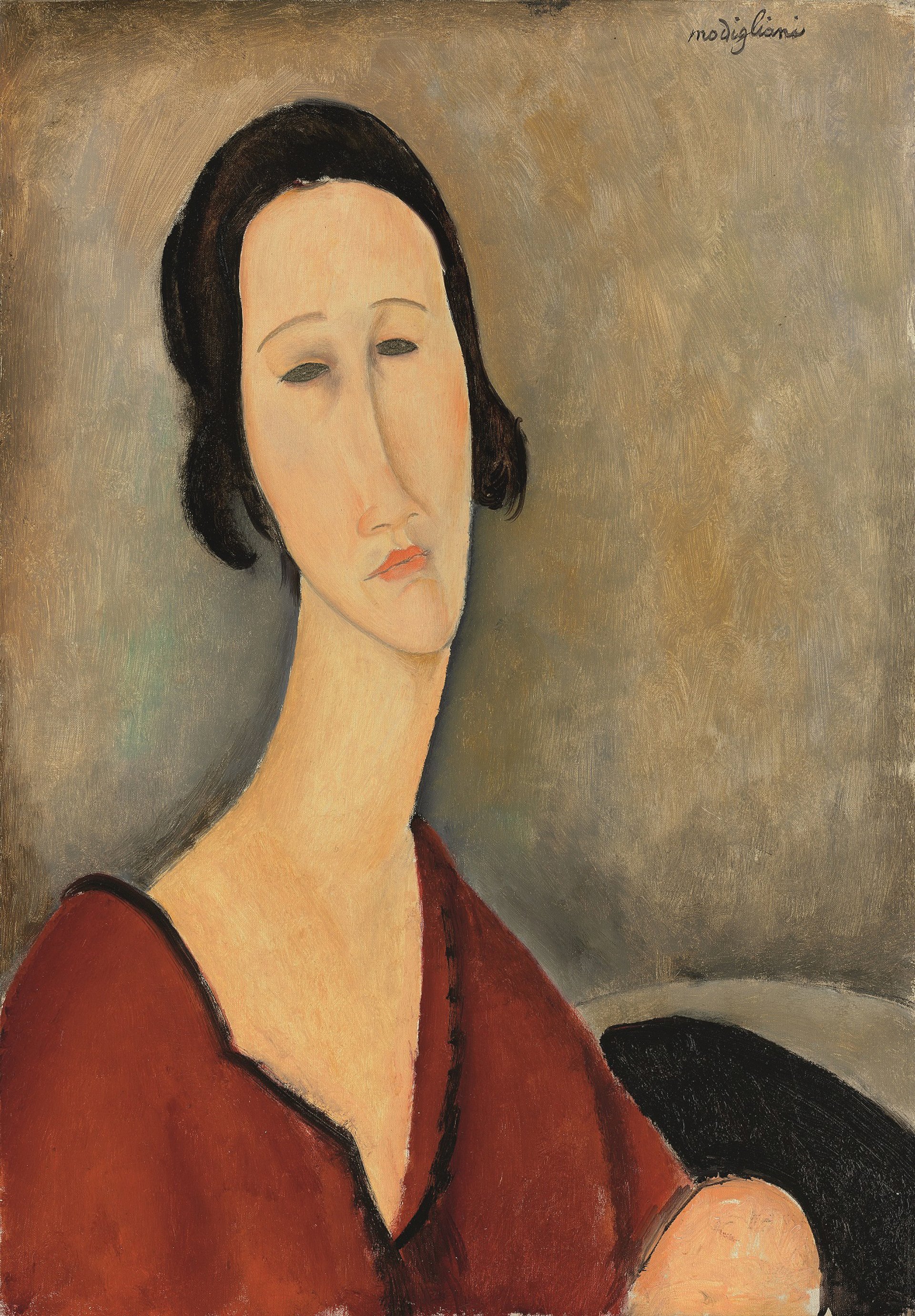

Amedeo Modigliani, Madame Hanka Zborowska (1917)

Sold at Christie’s, 22 June, for £7.3m (£8.3m with fees; est £5m-£7m)

The disappointing sale at Christie’s did have its positive moments. Portraits of Hanka, the wife of Leopold Zborowski, the dealer who understood and promoted Modigliani’s work, are rare—there are only 11 of her in his catalogue raisonné, which numbers 340 works. Three or four of them are in museum collections. “This work was reasonably estimated, in good condition and had been in the same English family since the 1930s. It ticked all the boxes,” says Olivier Camu, who sold the work on the phone to an “old-world, private collector”. The market for Modigliani is in rude health, not least because of the record-breaking sale of Nu couché (1917-18) for $152m ($170.4m with fees) at Christie’s New York, in November 2015. His catalogue raisonné is also being tidied up and re-editioned (see pp4-5).