2000: I do, I undo, I redo Who: Louise Bourgeois, then about to reach her 90th birthday.

What: At the east end of the Turbine Hall, three steel towers—I Do, I Undo and I Redo—each nine metres high, with spiral staircases, mother-and-child sculptures, and vast circular mirrors around and within them. On the bridge over the space, a giant steel spider, Maman, with marble eggs in its belly.

The artist said: “I Do is an active state. It’s a positive affirmation. I am in control, and I move forward towards a goal or a wish or a desire. The Undo is the unravelling. The torment that things are not right and the anxiety of not knowing what to do. The Redo means that a solution is found to the problem. It may not be the final answer, but there is an attempt to go forward.”

The critics said: “The spider is silly, but the towers are solidly visionary pieces, with a touch of fairground, too—stupendous in scale, and frankly like helter skelters. Exactly the right note.” — Tom Lubbock, The Independent

“The sculptures are awful. Previously a neglected artist, Ms Bourgeois is now vastly overrated.” — Michael Kimmelman, The New York Times

Miscellany: Bourgeois never saw her creations in the flesh at Tate Modern. Her trusted assistant, Jerry Gorovoy, installed them according to scale models she had created in her studio in New York.

2002: Marsyas Who: Anish Kapoor, then yet to be renowned as the creator of gargantuan public art that he is today.

What: An enormous, blood-red form stretching the full 155m length of the Turbine Hall, and variously compared to a blood vessel, bodily organs and a trombone. Its title came from Titian’s The Flaying of Marsyas.

The artist said: “The work forms itself between three very large steel rings—it is stretched between them like a flayed skin. I am concerned with the way in which a language of engineering can be turned into a language of body. It is important that you can never get a view of the whole piece. It is jammed into the building so as to not allow anything but a partial view. The work must maintain its mystery and never reveal its plan. Perhaps then it becomes unobtainable. I want to make things that remain secret.”

The critics said: “You could say that Marsyas is playful, but it is like wrestling the world's biggest tapeworm. It manages something difficult—to be at once stupid and unforgettable.” — Adrian Searle, The Guardian

“This work is about glimpsing unspecific mysteries, standing in the presence of some enigma far greater than oneself. It is about the conjuring up of some nebulous and yet palpable feeling.” — Rachel Campbell-Johnston, The Times

Miscellany: Early in the installation, the red PVC membrane was installed inside out: it had to be peeled back so the process could be restarted, losing precious installation time.

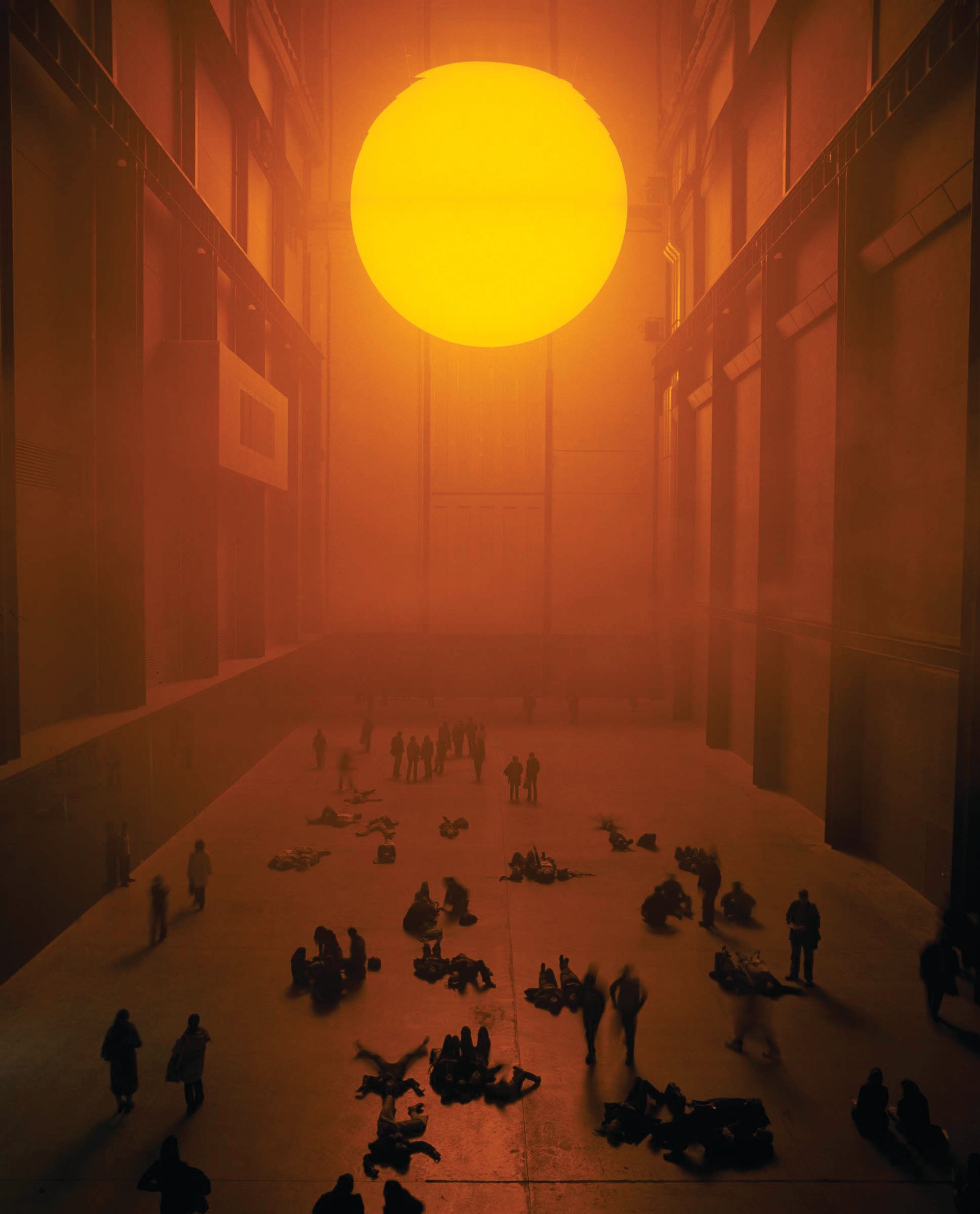

2003: The Weather Project Who: Olafur Eliasson, the Danish-Icelandic artist who was highly rated in the art world but hardly known to a broader public. How this would change.

What: A mirrored ceiling, a semi-circle formed from hundreds of mono-frequency lamps, and dry ice. These unpromising raw materials led to a sublime mystical spectacle of a sun over a misty duotone industrial cathedral, prompting all manner of spontaneous public gatherings. Eliasson’s project remains perhaps the best loved of all the Turbine Hall projects.

The artist said: “I would like to see The Weather Project at the Tate as raising a host of questions about how we see and experience ourselves and our institutions as such: about what art is in a museum, what a museum is in a city, what a city is in a country.”

The critics said: “Late on a Saturday or Sunday afternoon, when hundreds of people stand mesmerised in the face of the glowing disc, the work becomes truly frightening — a modern interpretation of one of John Martin's or Francis Danby's apocalyptic visions of the end of the world.” — Richard Dorment, The Telegraph

“[Eliasson is] from Iceland originally, and the scale being employed has been learned from looking across lakes and gazing at glaciers. The mood, meanwhile, created by dark mists pumped silently into the space is a twilit Norse miserableness that combines with the sublime size of the spectacle to achieve something genuinely impressive.” — Waldemar Januszczak, The Sunday Times

Miscellany: Eliasson conducted a survey of Tate staff, asking them questions about the weather. Questions included: “Do you think the idea of the weather in our society is based on nature or culture?” In case you’re interested, 47% said culture, 53% said nature. This and other stats appeared in the posters for the exhibition.

2006: Test Site Who: Carsten Höller, the Belgian artist who had come to prominence alongside other exponents of Relational Aesthetics in the 1990s but had not until then had a major show in London.

What: Five metal slides, emerging from Tate Modern’s boiler house into the Turbine Hall—two slides on the second floor, and one slide each on the three floors above. Höller had first created these slides in 1998 in Berlin, but these were his most dramatic yet.

The artist said: “It would be a mistake to think you have to use the slide to make sense of it. Looking at the work from the outside is a different but equally valid experience, just as one might contemplate The Endless Column 1938 by Constantin Brancusi… Slides deliver people quickly, safely and elegantly to their destinations, they’re inexpensive to construct and energy-efficient. They’re also a device for experiencing an emotional state that is a unique condition—somewhere between delight and madness.”

The critics said: “He says they are art and not art, these already famous fairground rides: but only a fanatic would find them more than artful. The G-force in the highest is frightening. Even the lowest sends you hurtling side to side. Slick as fireman's poles, undeniably exciting, they are simply the fastest exit from the pleasure dome.” — Laura Cumming, The Observer

“To a certain kind of cultural pessimist it might seem this is the final folly of a populist museum – to just turn itself into a chic fairground. Perhaps a bit of Höller is that cultural pessimist, for his intervention possesses an unresolved satirical ambiguity that makes it far and away the most intelligent [of the Turbine Hall installations].” — Jonathan Jones, The Guardian

Miscellany: Höller has long had bigger ambitions for his slides. He commissioned an architectural study for the show’s catalogue, assessing their use elsewhere in London. Their forthcoming permanent appearance on Anish Kapoor’s Orbit tower in the former Olympic Park in East London seems a natural, spectacular conclusion.

2007: Shibboleth Who: The Colombian artist Doris Salcedo had already shown her poetic-political sculptures at Tate Britain in 1998, but in the intervening years had begun to make larger sculptural statements.

What: A jagged crack running the length of the Turbine Hall, at points stretching to a foot wide, with steel mesh fence visible in the subterranean fissure. Much speculation focused on how it was made. While much jollity was had as people posed with the work, it had a serious message. The shibboleth relates to the gruesome Old Testament massacre of the Ephraimites; Salcedo used the term to reflect divisions in our own age.

The artist said: “It represents borders, the experience of immigrants, the experience of segregation, the experience of racial hatred. The space which illegal immigrants occupy is a negative space. And so this piece is a negative space."

The critics said: “After I left the hall, Shibboleth rattled around in my head all day, and it haunts me still. When I ask myself why, I realise it is because it looks like a wound, a gash that can't heal. It offers no hope, leaving you feeling as empty as the abyss it opens up beneath your feet.” — Richard Dorment, The Telegraph

“The rule is: the bigger the spectacle, the more it’s in danger of seeming simply a spectacle, the more inexpressibly significant it must be – in compensation, so to speak. And I can hardly tell you all the things that the crack in Tate Modern turns out to mean. But if you consult the accompanying Tate literature, you'll find it holds a real festival of the interpreter's art.” — Tom Lubbock, The Independent

Miscellany: When the crack was filled in following the closure of the exhibition, it left a permanent scar on the Turbine Hall floor.

2010: Sunflower Seeds Who: Ai Weiwei, six months ahead of his arrest in Beijing and long incarceration.

What: A bed of more than 100 million porcelain sunflower seeds, each hand made, occupying the east end of the Turbine Hall. Intended to allude to the “Made in China” phenomenon, and to the cultural revolution, during which sharing sunflower seeds was a community activity amid poverty and hunger.

The artist said: “It is a work about mass production and repeatedly accumulating the small effort of individuals to become a massive, useless piece of work. China is blindly producing for the demands of the market… My work very much relates to this blind production of things. I am a part of it, which is a bit of a nonsense.”

The critics said: “It will no doubt have a huge audience at Tate Modern, one that might see it as no more than an entertaining spectacle and treat it like a day at the beach. Yet Sunflower Seeds is contingent, oddly moving and beautiful. It is like quicksand.” — Adrian Searle, The Guardian

“[The seeds] form a fragmented world, something atomised, smashed to rubble. And maybe that's what they're truly meant to portend: the fall of China's old guard, the dismantling of the totalitarian system, which will take place as surely as every tide will always turn.” — Andrew Graham-Dixon, The Sunday Telegraph

Miscellany: Visitors were meant to walk on the seeds, but the work was cordoned off just after it opened to the public, due to potentially hazardous ceramic dust. For six months, Ai’s work was neutered.

2012: These Associations Who: Tino Sehgal, jostling with Theaster Gates for the title of world’s most buzzy artist following his triumph at Documenta 13.

What: A crowd of people, all volunteers trained by Sehgal. They would run in flocks, engage visitors in conversation and gather for ominous chants based on philosophical texts. Appropriately, given that it was opened alongside the new Tanks at Tate Modern, it was the first live work in the Unilever Series.

The artist said: “I’m always asking: ‘What can we do instead of objects?’ And the museum is the right backdrop to do that, because when you see my work you think, ‘There’s not a giant sculpture in the hall but a large group of people doing stuff.’ So you have this comparison.”

The critics said: “Attention is what it is all about, this precious thing we scarcely give one another and which is both the substance and the object of Sehgal's work. We often speak of art as life-changing; this event truly has that potential in all its fullness and humanity. One learns about other people, and one learns about oneself. I shall never forget it.” — Laura Cumming, The Observer

“The work is less radical than it would like to be… To me the work, though enjoyable, felt polite, not anarchic. The artist has injected pleasing shots of energy and exuberance into the Tate, but the prevailing mood is that of a parlour game, not manning the barricades.” — Alistair Sooke, The Telegraph

Miscellany: Photography and filming were not permitted; official images of the work feature Sehgal with his performers in front of the Tate. Stopping the millions who saw the work from capturing it proved futile, however. Google is awash with images and video of the event.