July marks the 80th anniversary of the start of the Spanish Civil War. The conflict, which lasted until late March 1939, pitched the forces of General Franco and his allies from Nazi Germany and fascist Italy against the elected government of the Second Republic and its anti-fascist supporters. The struggle included the bombing of civilian targets made infamous by Picasso’s Guernica and the burning of church buildings such as Vich Cathedral, which housed precious murals created by José María Sert.

The conflict produced a watershed moment in the history of the protection of works of art in wartime. At around 7pm or 8pm on 3 February 1939, the foreign minister of the Republic, Julio Álvarez del Vayo, and the assistant director of the Louvre, Jacques Jaujard, signed the Agreement of Figueras. The chaos of the moment stood in stark contrast to the enduring significance of the event. The government of the Republic was in retreat, and Del Vayo had holed up in San Fernando Castle in Figueras, a relatively short drive from the safety of the border with France. A bombing raid carried out by General Franco’s forces that day had knocked out all electric power, and the agreement was signed in the castle’s grounds under the lights of an Opel car.

Transporting the treasures The agreement stipulated that the Spanish government would entrust to the International Committee for the Salvation of the Treasures of Spanish Art all the works it had evacuated to safe sites close to the Spanish-French border. The committee brought together representatives of major museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Louvre, and the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery in London. Members of the committee pledged to transport the Spanish treasures through France to the recently opened headquarters of the League of Nations, where, as a gift from the Second Republic, Sert had decorated the council chamber with murals.

Shortly afterwards, 71 lorries set off for the French border, hauling 1,842 crates that contained a cargo including 364 paintings and 180 drawings from the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. On 15 February, the Times in London reported that 115 works by Goya, 43 by El Greco, 45 by Velázquez, 38 by Titian and 25 by Rubens had arrived safely in Geneva; among the paintings by Velázquez was the masterpiece Las Meninas.

Never before had the great and good of the world’s leading museums worked together to evacuate to another country so many extraordinary works of art. In the years leading up to the Spanish Civil War, the international community had begun to develop measures to protect works of art in wartime. The 1899 Hague Convention on the Laws and Customs of War on Land outlawed the use of cultural sites in ways that could turn them into military targets—such as using them as arms dumps or as hideouts for snipers—and imposed a moral duty on combatants to respect cultural monuments.

During the First World War, the director of the British Museum, Frederic Kenyon—who would become closely involved in the International Committee for the Salvation of the Treasures of Spanish Art—oversaw the evacuation of vulnerable objects in his museum’s care to the National Library in Wales. From 1934, the International Office for Museums (attached to the League of Nations) had built on these achievements and developed a set of protocols for protecting works of art, either by building secure spaces within museums, as the British Museum had done during the First World War, or by creating safe sites away from conflict zones in areas designated as neutral territory.

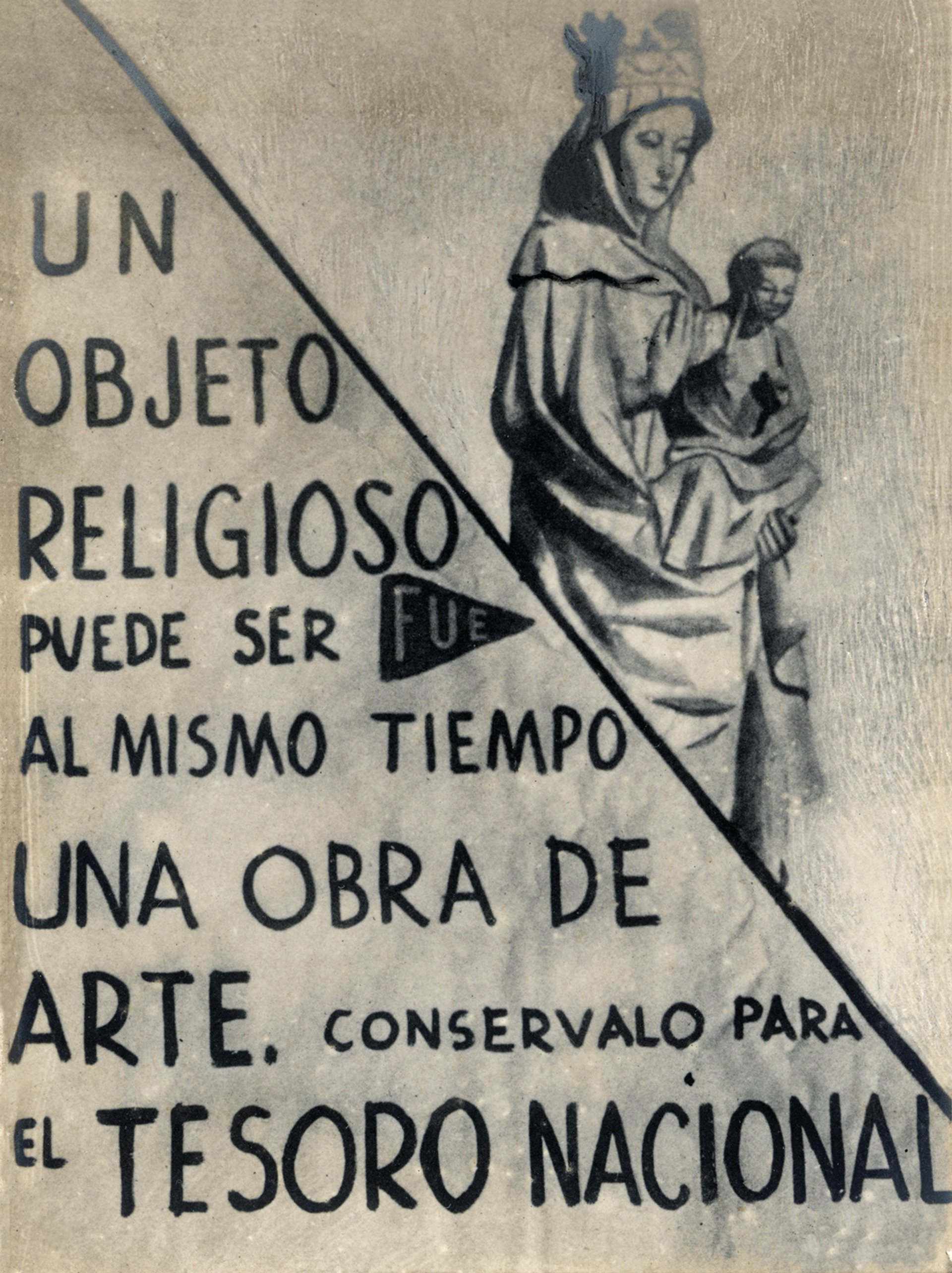

Preservation of heritage The story of how the Spanish government and the international community set a significant precedent in the evacuation of art is a terrible tale of the threat of destruction mirrored by extraordinary efforts to preserve the country’s world-class artistic heritage. Two great threats loomed over Spain’s great art collections during the Civil War: revolutionary iconoclasts and bombardment. The conflict had begun with a coup that was defeated by armed workers in many major cities in Spain, such as Madrid and Barcelona. In Catalonia, for instance, up to 40,000 weapons seized from army barracks had fallen into the hands of left-wing activists. The arming of the workers paved the road to revolution, and activists seeking to create a new world destroyed symbols of the old order, particularly churches and religious works of art. A vivid account of the destruction was left by the British communist Ralph Bates. He sat on a committee in the Pyrenean village of Espot, which condemned “revolting” statues of saints to the flames, while preserving statues that were considered to possess great artistic merit.

Supporters of General Franco exploited the iconoclasm in their propaganda campaigns. In Francoist-held Granada in 1938, for instance, a book entitled The Destruction of Spain’s Artistic Treasure from 1931-37 described the destruction of 731 churches. The powerful propaganda campaign hampered the government’s efforts to promote itself at home and abroad as the defender of democracy and of law and order.

Cultural enlightenment The Alliance of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals for the Defence of Culture worked to overcome the damage done by rebel propaganda. Its origins lay in the period before the Civil War, when many centre, socialist and communist-leaning intellectuals identified the Republic with progress and enlightenment. They also believed that people in rural Spain, who were starved of culture, would become better citizens by visiting their “circulating museum”, which displayed replicas of great Spanish paintings housed in the Prado.

From the start of the conflict, members of the alliance began to take over the homes and treasures of aristocrats or clergy who had been murdered or who had fled abroad. Famously, members of the United Youth of the Spanish Communist Party protected the Duke of Alba’s residence, the Palace of Liria, by impounding the palace and the masterpieces it housed, including Goya’s portrait of the Duchess of Alba, alongside works by Rembrandt, Rubens and other masters.

On 23 July 1936, the government took its first step in recovering control from militia groups by establishing the Junta for the Preservation and Protection of Spain’s Artistic Treasures. The junta in Madrid came under the control of Carlos Montilla, who expropriated in the name of the defence of the nation’s heritage all the publicly and privately held works of art he could find. He also ensured that the objects he took into care were catalogued and protected, by co-operating with what he described as the “laudable” militias of the Communist Party. He complemented this protective work with propaganda and began to publish lists of works of art that had been saved from iconoclasts, plunderers and art pedlars on the international black market.

This double-edged struggle to protect works of art and win the propaganda war also explains a government decree that was passed on 19 September 1936, naming Pablo Picasso as the head of the Prado. In fact, the artist never travelled to Madrid to take up his appointment. As the alliance’s newspaper, Mono Azul, pointed out in September 1936, Picasso shone as the most impressive international symbol of Spanish culture, and now he had allied himself to the “struggle against fascism”.

The Francoist bombing of Madrid strengthened the government’s propaganda campaign. On 16 November 1936, the general’s planes struck the Prado with nine incendiary bombs. The next day, 18 incendiary bombs severely damaged the Liria Palace, and only the sterling efforts of militia men saved the valuable art collection from destruction. As early as December 1936, the government had mounted an exhibition in Valencia featuring works saved from the bombed palace. An accompanying propaganda pamphlet declared that the show had been “placed before the civilised world as living testimony of the culture rescued by the anti-fascist people”.

The exhibition formed the first stage of the government’s three-fold evacuation of national treasures. This initial move from Madrid to Valencia was followed by a transfer to Catalonia and finally the evacuation to Geneva. The government side presented the removal to Valencia as a response to the “fascist” bombings, but in reality, the evacuation had begun before the shocking attack on the Prado.

By early November 1936, Franco’s forces had arrived on the outskirts of Madrid. The government, anticipating that the city would fall, headed for the relative safety of Valencia on the night of 6 November. It fell to members of the Alliance of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals, working in tandem with the Communist Fifth Regiment, to evacuate masterpieces from the Prado. It proved dangerous work, and when Rafael Alberti and his partner, María Teresa León, were transporting Las Meninas through the streets of Madrid, they came under attack from bombs. Forced to take cover, they left the great work in the street, just outside the alliance’s headquarters in Linares Palace.

Government intervention In Valencia, however, the government took great care of the treasures. The twin round towers of the Torres de Serrano housed most of the hundreds of pictures evacuated from the Prado. In September 1937, Frederic Kenyon reported in the Times on his visit to the towers, noting approvingly that they had been reinforced with concrete and earth. He also observed with satisfaction that the pictures were in stout, fire-proof cases. Kenyon’s findings put to rest Francoist allegations that the Republican government had been selling the nation’s treasures on the black market or had treacherously sent them to the Soviet Union.

In 1938, Valencia became a vulnerable part of the war front, so between March and April, the government’s National Junta for the Protection of Artistic Treasure, led by the artist Timoteo Pérez Rubio, oversaw the transfer of Spain’s great art collection to Catalonia and then Geneva. In Catalonia, the works were stored in Peralda Castle, in La Vajol mine and in San Fernando Castle, Figueras. After the works reached Geneva, the Herculean efforts of the government won praise from Neil MacLaren and Michael Stewart of the International Committee. They testified in a letter to the Times in May 1939 that only a few pictures had been damaged during their various journeys. Goya’s Dos and Tres de Mayo, for instance, had suffered when a balcony damaged by bombing collapsed on their cases, but the paintings had largely been restored before leaving Spain.

Rewriting history In Spain, the Republican government’s efforts went unrecognised for years. The Franco regime’s victory in the war, soon after the treasures reached Geneva, left it free to write its own history. Throughout 1939, the Francoist-controlled ABC newspaper criticised the “Reds” for “robbing” Spain of its treasures. The Francoists, with the help of Sert, among others, had negotiated the return of the pictures to Spain, but first there would be an exhibition of the masterpieces in Geneva. The show reflected the hardline nationalism of the Franco regime, with the principal gallery given the name Imperial Room, while 112 Spanish works on display dominated those of other nationalities. In Spain, the regime trumpeted the recovery of the treasures as the result of Franco’s “fine wisdom”, and in September 1939, all the works returned home to great fanfare.

The Francoists set about returning expropriated art, but they also persecuted some of those who had saved works and long remained silent about the Republic’s role in protecting Spain’s treasures. For instance, Franco’s regime liaised with the Gestapo to extradite Carlos Montilla from exile in occupied France. Once in Spain, he was prosecuted in a military court and was incarcerated in a dank, cold prison in Pamplona. Timoteo Pérez Rubio went into exile. Only in 1996 did the first museum in Spain mount an exhibition honouring his work (in Badajoz), and not until 2003 did the Prado commemorate the achievements of the junta run by Pérez Rubio in protecting a total of 27,000 public and private works of art.

In 2010, the Prado hosted the Spanish prime minister, the socialist José Luis Zapatero, who honoured the work of both Pérez Rubio and the International Committee. Speaking in the gallery displaying Las Meninas, he lavished praise on “the biggest effort to save works of art in history”.