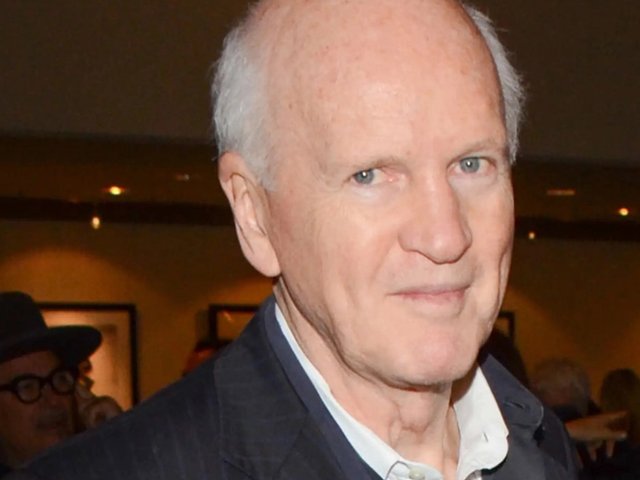

The outlook for Douglas Chrismas, the founder of one of Los Angeles’s oldest and largest galleries, seems to be growing bleaker by the day. Sam Leslie, the forensic accountant who now runs the day-to-day operations of the gallery, has officially terminated Chrismas’s role with Ace Gallery and has filed a lengthy status report to the court, documenting millions of dollars diverted to mysterious accounts and dozens of works of art that have been moved to private storage.

In an unusual twist to Ace’s long-running Chapter 11 bankruptcy case, Leslie took over the gallery as a court-appointed financial manager last month to implement a reorganisation plan. While he had previously discussed keeping Chrismas on as some sort of curatorial consultant, he wrote in the May report that he ended Chrismas’s involvement in the gallery after a review of Ace’s financial records.

“As detailed below, my review of the books and records of ACE have lead [sic] me to conclude that during the Chapter 11, significant sums of money were diverted by Chrismas to affiliates of Douglas Chrismas, ie, ACE Gallery New York Corporation and ACE Museum. I have as of May 10, 2016, terminated his role with ACE operations.”

Later, he specifies the amounts. Over the period from February 2013 to February 2016, Leslie says that a total of $16,910,139 directed to Ace New York. Of that sum, he says $4,568,382 was diverted to an entity known as the Ace Museum.

Both companies are a mystery, since Chrismas closed the New York branch of his gallery over a decade ago, and his “museum” on La Brea Avenue in Los Angeles has a spotty exhibition history.

What’s more, Leslie says that Chrismas instructed assistants to move 60 works of art from Ace Gallery to a private storage facility the day before Leslie took over management.

“I asked Chrismas to prove his ownership to me of these 60 pieces,” Leslie wrote in the report. “He told me had had acquired them years before, and when pressed, gave me dates in the early 1970s and 1980s, and he confirmed all works he allegedly owns predated the year 2000 in any event. None of these pieces, including one of significant value, were listed in the bankruptcy petition he personally filed in 2004.”

Attorney J. Scott Bovitz, who represented the painter Gary Lang in the Ace bankruptcy, says concealing assets in a bankruptcy case could result in criminal charges. “If the artwork was in fact his personal property, Mr Chrismas didn’t disclose it in his 2004 bankruptcy, and that’s a problem,” Bovitz says. “If it wasn’t his own property and he stole it from the bankruptcy estate this year, that’s also a problem. Either way, he has painted himself into a corner.”

Bovitz explained that transferring money out of a bankrupt estate could also qualify as a crime, depending on intent. “For example, making dumb payments to a landlord for a space you don’t need is probably not a crime, it’s dumbness.” But, he adds, “transferring money for your personal benefit could be a crime”.

It is not clear whether a criminal investigation is under way. Chrismas’s bankruptcy lawyer, David Shemano, did not have a comment at the time of publication.

Leslie’s lawyer, Carolyn Dye, confirmed that the US Trustee’s office, which oversees bankruptcy cases for the US Department of Justice, “received the report by the electronic filing copy and is aware of it”. But when asked about the matter, a spokeswoman for the Trustee’s office said: “It is our policy not to confirm or deny the existence of a criminal referral or investigation.”

In the meantime, Leslie continues to run the gallery with regular hours and existing staff, trying to make sales to satisfy creditors. The gallery is even opening a new group show on 11 June at its main location on Wilshire Boulevard. The exhibition includes work by John Armleder, Mary Corse, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Sylvie Fleury, Ben Jones, Jannis Kounellis, Gary Lang, Robert Longo, Dennis Oppenheim and Julian Schnabel.

UPDATE: After publication, David Shemano, Chrismas's bankruptcy lawyer, contacted us and made the following statement: "Douglas is unaware of any criminal investigation or any basis for a criminal investigation," noting without further explanation: "Douglas does not agree that there was any improper diversion of funds."