As Syrian troops drove the Islamic State out the ruins of Palmyra on Sunday, the world held its collective breath to see what was left of the World Heritage Site.

Detailed damage assessments are on-going, and early indications are mixed. The Palmyra Museum appears to have been hit by both artillery shells and acts of vandalism, with the faces or heads of some 20 statues hacked off in attacks that may have been motivated by the Quranic sin of idolatry, known as shirk. It also appears that five previously unpublished tower-tombs have been at least partly damaged.

The broader archaeological site, on the other hand, appears to have been largely spared after the dramatic destructive acts that Isil broadcast to the world last summer, when it detonated the Temples of Bel and Baalshamin along with the Arch of Triumph in quick, choreographed succession.

Today, we know that the site’s majestic amphitheater, rows of columns and other iconic ruins were laced with explosives by Isil, but ultimately spared.

These early assessments contain several important lessons for those of us who watched the destruction of Palmyra in horror last summer—and then shared it virally on social media.

First, they lend credibility to on-the-ground reports during the city’s harrowing occupation that the Islamic State’s destruction of historical monuments was motivated less by twisted ideology than a far simpler craving for attention.

“In-country sources… have overheard Isil commanders comment that attacking the ancient monuments ‘makes the whole world’ talk about them,” noted a September report from the American Schools for Oriental Research, an archaeological group tasked by the US State Department with monitoring heritage destruction in Syria and Iraq.

Notably, the destruction of historical sites had started months earlier, after international media outlets had collectively decided to stop broadcasting gruesome images of Isil hostage beheadings.

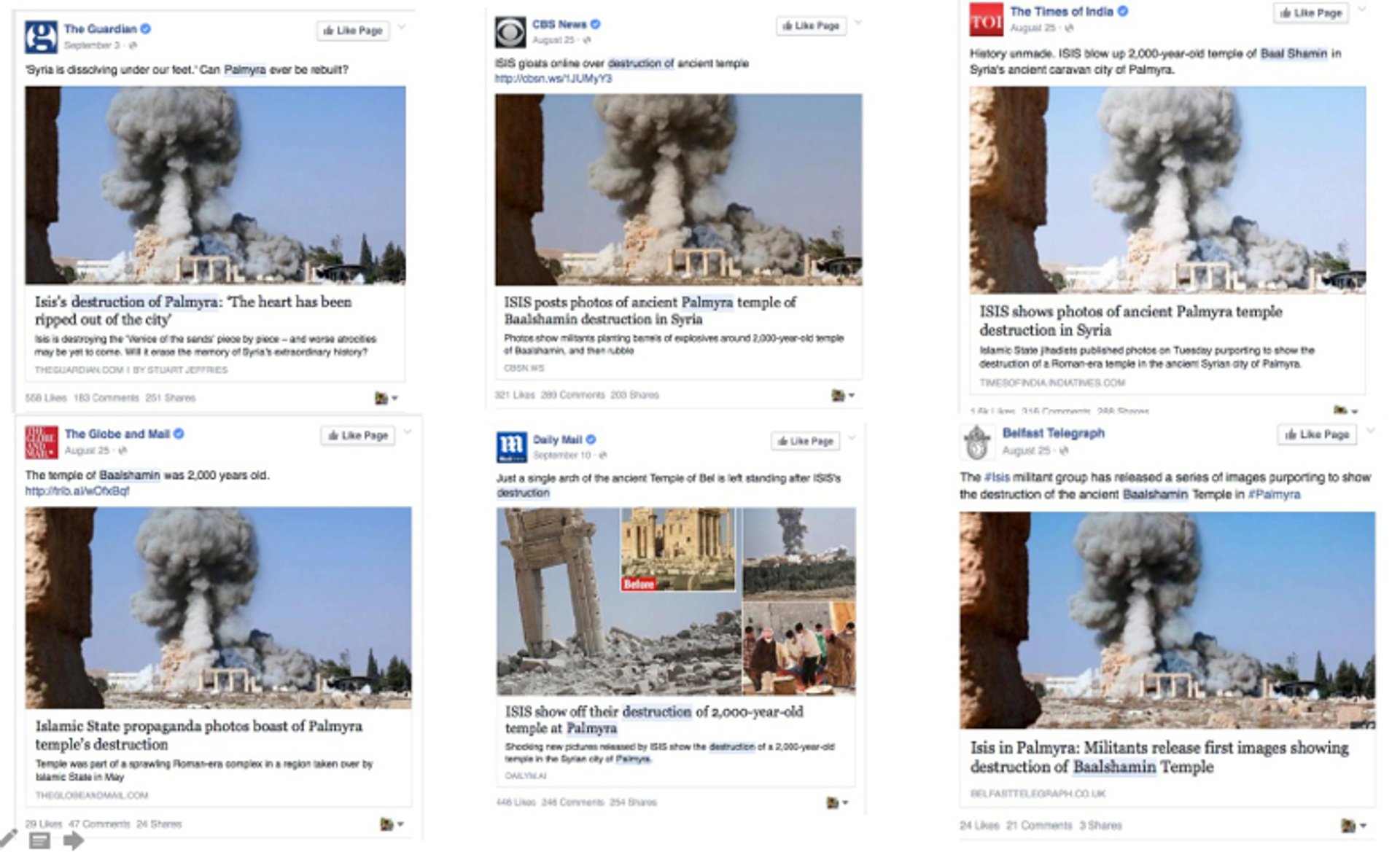

If media attention was indeed what Isil had wanted, the destruction of Palmyra was a coup. Respected international media outlets republished Isil’s carefully choreographed shots of the detonation of the iconic Baalshamin Temple on social media as if they were news photos, not the propaganda of a terrorist regime.

In Palmyra, we first witnessed the collision of iconoclasm and clickbait.

Iconoclasm, the destruction of icons for religious or political motives, is nothing new. At a symposium organised with Harvard University's Standing Committee on Archaeology last winter, we joined a group of scholars to explore the act’s historical roots, from the sixth century BC destruction of Nubian statues in Egypt, to the late medieval defacing of Christian images in England, to the destruction of church bells by Pueblo Indians in the American Southwest in 1680.

The goal of iconoclasm is the annihilation of an idea through the public destruction of an object that represents it. But to be effective, history suggests these acts need an audience. Following the 2001 destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, the Taliban regime organised guided tours of the World Heritage site for western journalists. The 2003 toppling of Sadaam Hussein’s statue in Baghdad’s Firdos Square became iconic because it was caught on film.

That’s where clickbait comes in. Today’s use of social media to spread viral content—the cute cat videos, listicles and teaser headlines that pervade the internet—have proven powerful tools to draw new online audiences. Clickbait was distilled into a science by websites like Upworthy and Buzzfeed, and is now being adopted by legacy media like the Washington Post as they scramble to replace evaporating revenue streams.

Increasingly, modern media is funded by clickbait and the advertising revenue it generates.

This fact was not lost on Isil, whose sophisticated propaganda machine has created pre-packaged viral content—slick YouTube videos, Facebook posts and 140 character Tweets—designed to be spread on the web.

It is Isil’s ability to marry ancient iconoclasm with modern clickbait that has spread their appetite for destruction so far and fast. And it is our fascination with sharing their snuff films on social media that make us complicit in their crimes.

Confronted with Isil’s viral iconoclasm, experts who monitor the destruction have debated how to respond. Some have elected to stop sharing information with the public, fearing the attention will only fuel further destruction. Omur Harmansah, a specialist in the art, architecture and archaeology of the ancient Near East at the University of Illinois at Chicago, has argued that “what we treat on our Facebook profiles, tweets, and blogs as documentation of violence is in fact the raison d’etre of Isis’s biopolitics.”

Others, like Stephennie Mulder, associate professor of Islamic art and architecture at the University of Texas at Austin, argue that we are naïve to think that self-censorship will stop Isil’s heritage destruction; the silence of experts will leave only only the terrorists speaking.

With the recapture of Palmyra, everyone with a Facebook account should consider the debate.

So, what to do?

In our view, first and foremost we must understand Isil’s destruction for what it is: an ancient tool used by insurgents to legitimise their power by erasing the symbols of those who came before. While we may be powerless to stop the destruction in Syria and Iraq, we can and should refuse to spread it.

As experts who monitor this destruction, we must be cautious but not silent. We should put these acts of iconoclasm into a historical perspective by sharing our research with the public and helping journalists separate fact from propaganda.

War, not iconoclasm, is responsible for the vast majority of the cultural heritage damage in Syria and Iraq, and the Islamic State is one of several actors responsible. Indeed, Palmyra suffered significant war damage before Isil ever arrived.

As members of the media, we must cover iconoclasm without becoming complicit in their crimes by spreading Isil propaganda uncritically, especially on social media. When we do use their images, we should clearly label them as propaganda, not treat them as news images. And as tragic as the loss of historical sites like Palmyra may be, we should not let it outshine the plight of Syrian civilians.

We have a model for this path: it was done successfully after Isil began broadcasting videos of hostage beheadings. After the killing of American journalist James Foley spread across the internet in August 2014, media organisations, experts, social media companies and the general public voluntarily stopped the spread of subsequent beheading videos. They soon lost their power for Isil.

By January 2015, with its propaganda efforts flagging, Isil abandoned the staged executions and began its campaign of spectacular destruction of archaeological sites. Those in turn stopped when Isil launched coordinated terror attacks first in Paris and now Brussels.

Looking back, we should have been as reluctant to spread images of the choreographed destruction of heritage as we were of humans.

• Jason Felch, our Los Angeles correspondent, wrote the book Chasing Aphrodite on the illicit antiquities trade. Bastien Varoutsikos is an archaeologist at CNRS, The National Center for Scientific Research in France, and Secretary of the organisation Heritage for Peace.