This year, a new buzzword entered the Japanese dictionary—bakugai. It means a buying explosion and was coined to describe the kind of reckless spending spree embarked on by wealthy Chinese tourists in Tokyo.

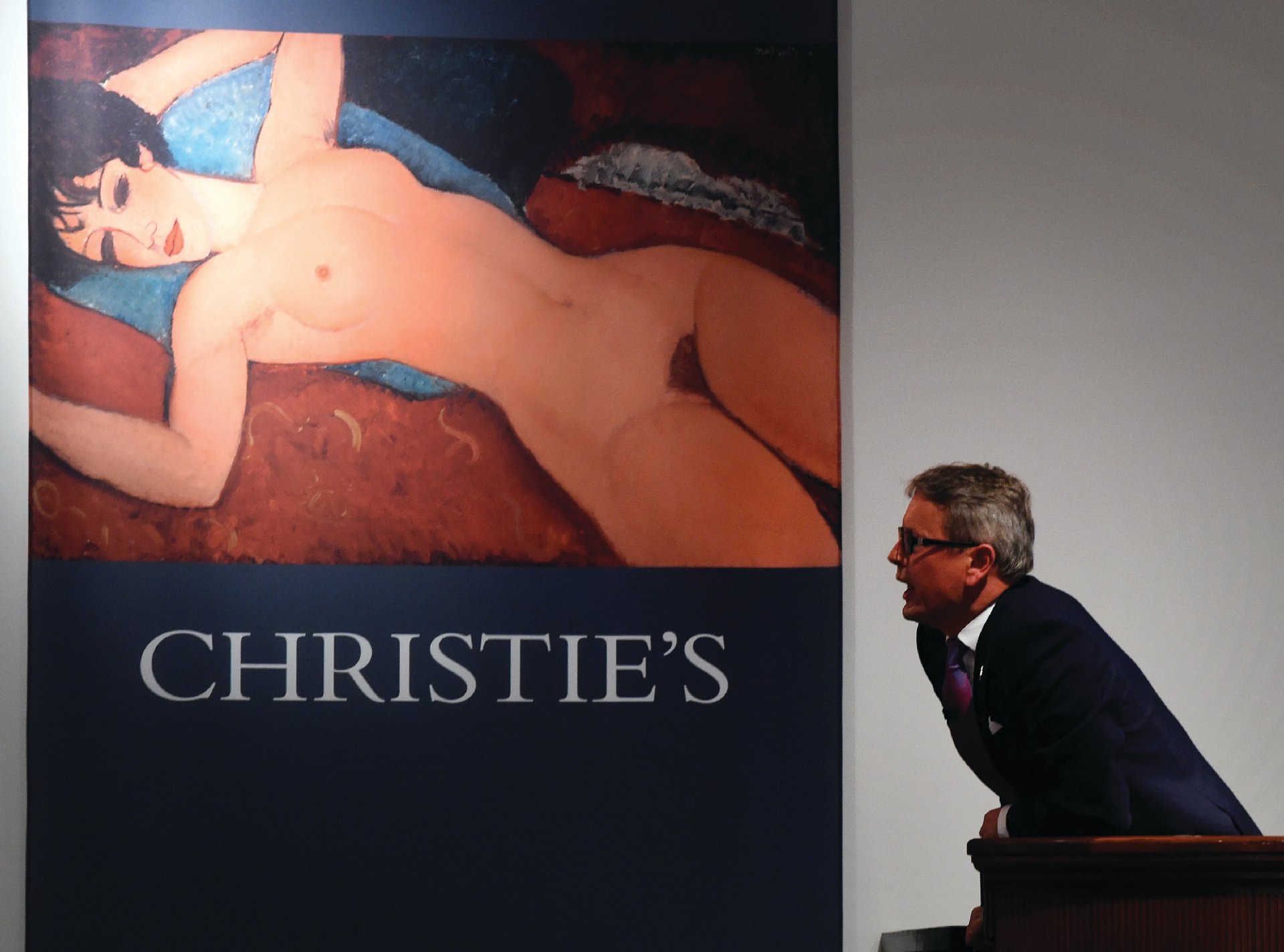

Since 2011, something similar has happened in Christie’s and Sotheby’s global salesrooms. Now, though, it looks increasingly likely that the $170.4m purchase of Modigliani’s Nu couché by the taxi driver-turned-billionaire businessman and art collector Liu Yiqian, at Christie’s, New York in November, was the high-water mark of the art market’s most recent bubble.

For long-term Japan watchers, bakugai might just as easily have described the actions of Japanese speculators during the late 1980s, when the combination of high Japanese share prices and the low yen cost of art led to a speculative frenzy around the markets for Impressionist and post-Impressionist art.

The Japanese bubble reached its peak in May 1990, with the sale of Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet to the paper manufacturer Ryoei Saito for a record $82.5m, leaving all three of the world’s most expensive paintings in the hands of Tokyo investors (the other two were Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette and Van Gogh’s Portrait of Joseph Roulin) by the end of the month. Reality soon caught up, however, and decades of stagnation have followed.

In the aftermath of the crash, and the firesale that ensued, three-quarters of all Japanese galleries went bankrupt. These days, the sum total for art at auction in Japan regularly scrapes in under $60m a year, which represents less than 0.5% of the global art market.

Now, with the Chinese stock market reeling and the yuan plunging to a six-year low against the dollar, the question many are asking is how post-boom China can avoid the problems Japan has faced. The Chinese art market has already experienced a “significant decline” in 2015, with sales dropping 23% to $11.8bn compared with the previous year, according to the latest edition of Tefaf’s annual art market report by Clare McAndrew.

Meanwhile, in Japan, “the collector base evaporated along with the bubble”, says Ashley Rawlings, the director of Blum & Poe’s Tokyo outpost. “This was made worse by the fact that there is no tradition of donating to museums as there is in the West, nor are there the tax incentives to do so.”

With a 50% inheritance tax and low levels of executive remuneration, the top tier of collectors in Japan is very thin. Modern China, on the other hand, has a much broader collector base. The Forbes billionaires list for 2015 has just 24 Japanese names compared with 213 from China, or 53 from the UK—a country with half Japan’s population.

To many in the Tokyo art world, one of the most negative legacies of the bubble (apart from the catastrophically high cost of gallery space in central Tokyo) is that during its peak influence and power, Japan did so little to promote its own living artists.

“The focus was on imports from Europe. In other words, recognised artists took precedence over up-and-coming ones,” says Cléa Patin-Miyamoto, the associate professor in the Japanese Studies department of Jean Moulin University in Lyon, and the author of the forthcoming book, Making Art in Japan: a Sociological Portrait of an Art Market. “The number of bankruptcies explains the risk aversion in the Japanese art world today. And risk aversion is particularly a disadvantage in the contemporary art world, which is by far the most uncertain.”

There have been a number of attempts to remedy this, including the culture ministry’s much derided Cool Japan campaign, and, more credibly, Geisai, the biannual art fair set up by the artist Takashi Murakami to encourage young contemporary artists.

Despite such efforts, and the belated critical success of the Gutai and Mono-ha movements, many believe that Japan has missed its chance to take its place as an art world power.

“I’m not optimistic about the short-term forecast,” Akira Asada, the critic and cultural theorist, says. “The market here is still dominated by classical painting. Right now, China and Korea have much more vigorous cultural agency. Meanwhile the Japanese budget for cultural exchange is dwarfed by its equivalents in China and Korea.”

For the Japanese art world, the consequences of its own explosive buying spree have been just as destructive as the term suggests. Time will tell if the Chinese market is strong enough to absorb the coming shock, or whether, like Japan, it will be picking up the pieces for years to come.