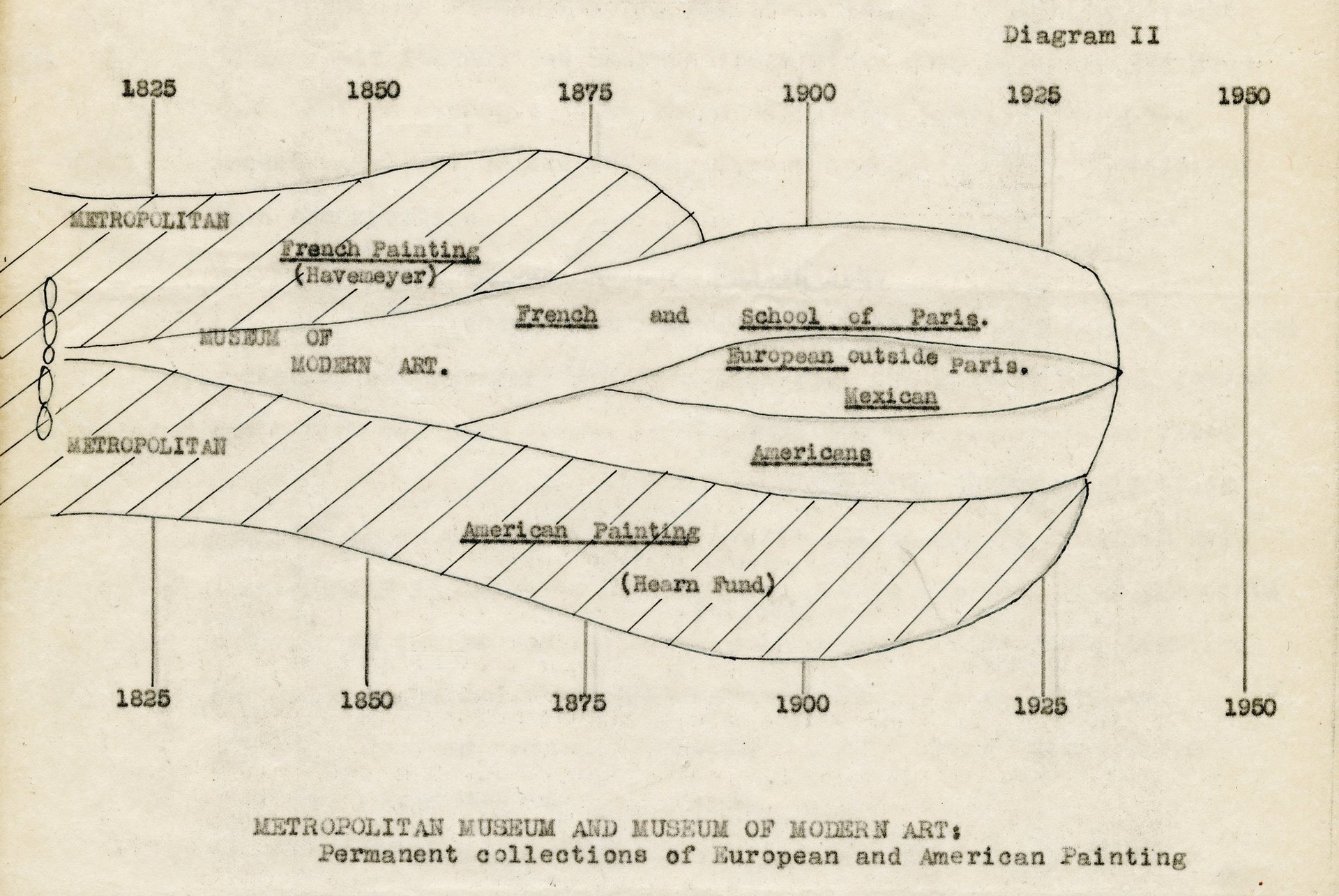

Two images haunt the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s engagement with the contemporary. One of these is the famous Life magazine photograph of 15 New York School artists—the so-called “Irascibles”—who protested the museum’s conservative stance toward contemporary art by refusing to submit work for the exhibition American Painting Today, 1950. The other image is the “torpedo diagram” created by Alfred Barr, the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The drawing illustrates his conception of what MoMA’s collection should be: a torpedo moving through time that incorporates the new as it jettisons the old in order to focus on the present. The recipient of that jettisoning was to be the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Restraint of trade pact Barr’s notion of the Met as a repository for no-longer-contemporary art was realised as a formal policy for only a few years. An agreement in 1947 was annulled in 1953, eventuating in the transfer of only around 40 works from one museum to the other. By this time, the Whitney Museum of American Art had entered the picture and the trio had formed the Three Museum Agreement, a restraint-of-trade pact that specified particular collecting realms. MoMA was to specialise in American and “foreign” Modern art, the Whitney in American art and the Met in “classic” art.

The situation was complicated by the fact that the Met had informally agreed in 1943 to absorb the Whitney’s holdings and show their American collections together in a new wing. Fortunately, this plan was abandoned—the Whitney’s trustees having had “grave doubts” about whether the institution’s liberal spirit could be preserved under the Met’s roof. The aborted proposal provides historical resonance to the Met’s recent move into the Whitney’s former home on Madison Avenue, designed by the architect Marcel Breuer.

Renamed the Met Breuer, this 1966 structure now houses the third strut of a three-part institution that includes the Met Fifth Avenue and the Met Cloisters, according to the museum’s newly adopted nomenclature. With an eight-year renewable lease, the Met Breuer is part of an ambitious effort to turn the page on the Met’s modest history with contemporary art. (An exception to the museum’s poor record in this arena was the exhibition New York Painting and Sculpture 1940-1970, curated almost 50 years ago by Henry Geldzahler, then aged 33.)

Given the significant public visibility of contemporary art and the immense wealth directed at collecting it, the Met can ill afford to sideline this field, as it felt comfortable doing in the past. The Met Breuer is part of a significant redirection of institutional strategy, which will include a new $600m Modern and contemporary wing to be designed by David Chipperfield.

By moving into the Breuer building, the Met has attracted much more attention to its revised Modern and contemporary programme than it would have been able to do in the existing space on Fifth Avenue. Of course, the reopening of the building has also provided an occasion for publicity, including a rebranding campaign and a controversial new logo. Most importantly, by appropriating the former Whitney building, the Met now occupies a central site in Manhattan’s existing topography of museums devoted to Modern and contemporary art. Audiences already associate the Breuer building with the new. Now, the Met must present exhibitions and programmes that measure up to this distinguished location.

New priorities The Met Breuer makes important statements about the museum’s overall Modern and contemporary project, led by Sheena Wagstaff, the former chief curator at Tate Modern in London. The loving restoration of this modern landmark points to her department’s new commitment to architecture and design. (Wagstaff has also appointed the first full-time curator devoted to the subject.) The department’s expanded focus here echoes the pioneering interdisciplinarity of MoMA, but also harks back to the Met’s own early interest in the training of designers and artisans. ;

Other curatorial appointments indicate a reorientation from the Eurocentric to what has been termed “other Modernisms” and “the global contemporary”. But these new positions—dedicated to the art of Latin America, South Asia, and the Middle East, North Africa and Turkey—are not merely a reflection of the current cultural moment. They make perfect sense within a universal survey museum whose riches and expertise are organised geographically. There is an old-fashioned term for what this change promises: synergy.

Synergy between Met departments of the old and the new is realised in the Met Breuer’s highly anticipated opening exhibition, Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible (until 4 September). Here, the museum leads with its strengths: a historical collection of great depth and the institutional prestige to bring in such stunning loans as Titian’s The Flaying of Marsyas (1570-76), which opens the show.

The exhibition features a litany of great works—Leonardos, Poussins, Rembrandts, Turners, Picassos—that relate in various ways to the concept of “unfinishedness”. A basic typology distinguishes works that are finished but looked unfinished to their contemporaries—the non finito—from those that were left incomplete due to circumstance, including the death of the artist. Moving from the Renaissance to the present, the exhibition displays how radical change in what counts as “complete” reveals much about our evolving conceptions both of the artist and of works of art.

The show’s chronological structure misses opportunities to juxtapose works from distant periods, and it is difficult not to be overwhelmed by the older pieces in comparison with the contemporary ones. But the moments of emotional power and sheer beauty in the exhibition attest to the fecundity of its organising concept. It is filled with revealing connections between artistic process and ideation, such as the contrasting notions of virtuosity exemplified by Michelangelo’s head and hand in Daniele da Volterra’s portrait of the master (around 1544) and the loose brushwork of Frans Hals’s The Smoker (around 1623-25).

Aesthetic of enduring authority Unfinished is a wholly Euro-American affair. The global perspective of the Modern and contemporary programme is represented by a survey of the Indian Modern artist Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990). This elegant and moving show is an ideal foil to the boldness and high art historical drama of Unfinished. It combines the small geometric abstractions that Mohamedi created with fine pen and graphite, her sensitive photographs of abstract architectural forms and her tiny diaries. While each element of the show is small, they sum to a great deal, revealing a quiet aesthetic of enduring authority.

The third offering at the Met Breuer is performance, something that it seems no contemporary art museum can now do without. The Met has embraced the genre with characteristic high achievement. In a small gallery off the lobby, the brilliant pianist Vijay Iyer took up residence during March, offering a changing daily programme of musical improvisation with a range of invited collaborators. There also will be performance in the galleries, another increasingly common feature of current museum practice.

The choice of Iyer is representative of what the Met Breuer promises to deliver: a strong, serious programme that will add to the city’s extraordinary cultural offerings. Next to come are early photographs by Diane Arbus and a retrospective of the African-American painter Kerry James Marshall. Experimental forays? No. Timely and important works of quality? Yes. In a city with no shortage of contemporary art, substantive presentations like these are what we should expect from the Met.

Most exciting, however, is the model presented by Unfinished, in which the museum deploys its outstanding collections to explore art-making across broad cultural and temporal fields. When imaginatively brought into the present, historic works can participate in exhibitions that are as current as any strictly contemporary art show. This is not about the eternal values of art. Rather, for artists and for the rest of us, a penetrating conversation among works of art can be nothing other than contemporary.