Artists make discoveries about their work each time they mount an important show; we spoke to six about the exhibitions that marked turning points in their careers—for better or worse.

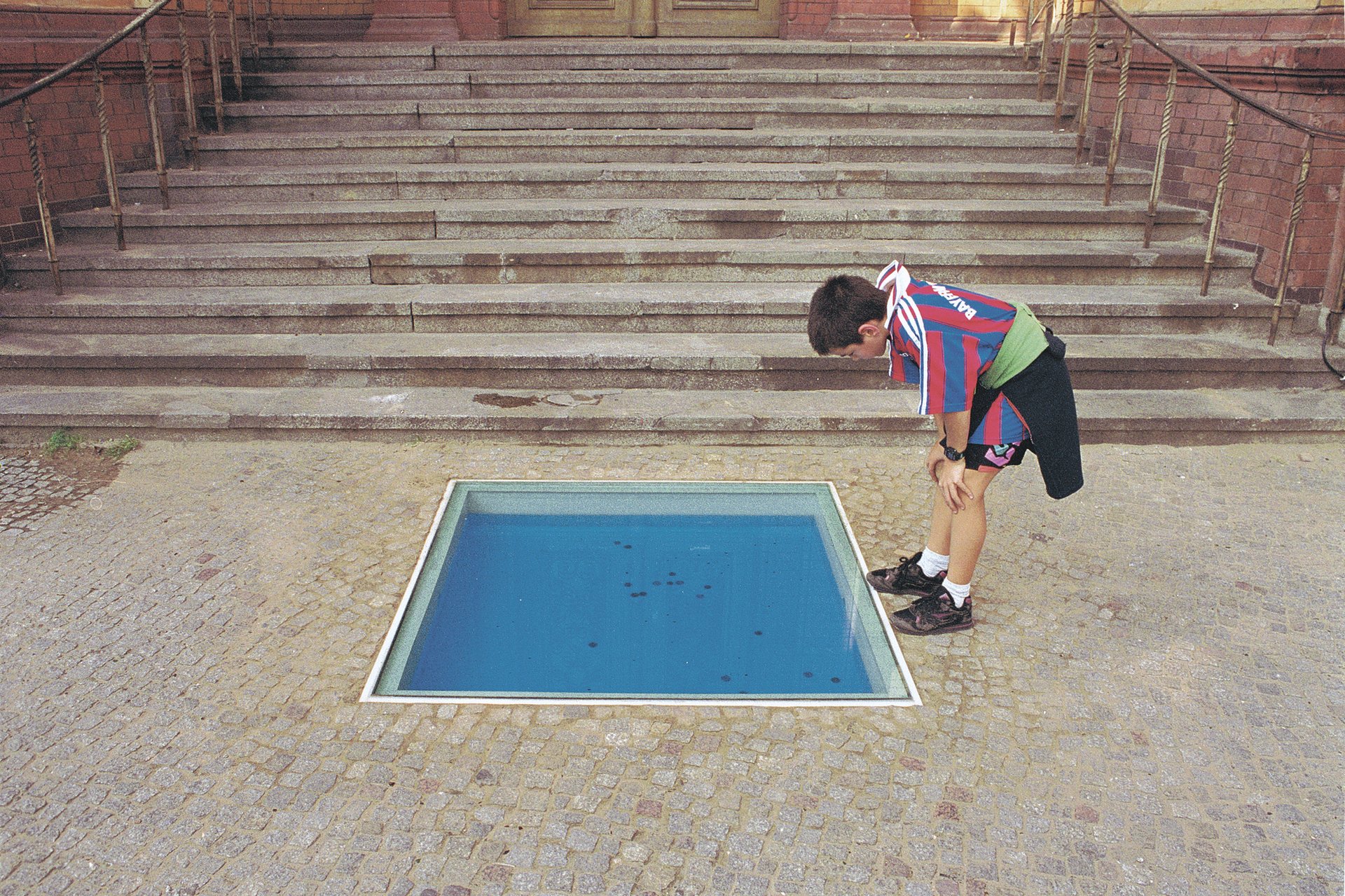

ELMGREEN & DRAGSET Being included in the first Berlin Biennial, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, Nancy Spector and Klaus Biesenbach in 1998, was an eye-opener for us. We really experienced, for the first time, the international art scene. We had just moved to Berlin from Copenhagen and had only been included in one major group show before. We didn’t work with a gallery, we had no clue about markets and power plays by private dealers or collectors, and we hardly knew any critics or curators. We installed a sealed-off “wishing well”, dug down into the pavement at the entrance to one of the venues. It was a square basin with bluish water, and at the bottom was a selection of coins from the Danish mint without the value printed on them. A powerful gallery representing another artist tried to persuade the biennial to move our work to another spot because its artist felt we were too close. Fortunately, Nancy Spector stood up for us and said no. We were quite innocent then—however, this taught us how private interests often try to influence even events as public as biennials. We also learned that it is important to have support structures as artists.

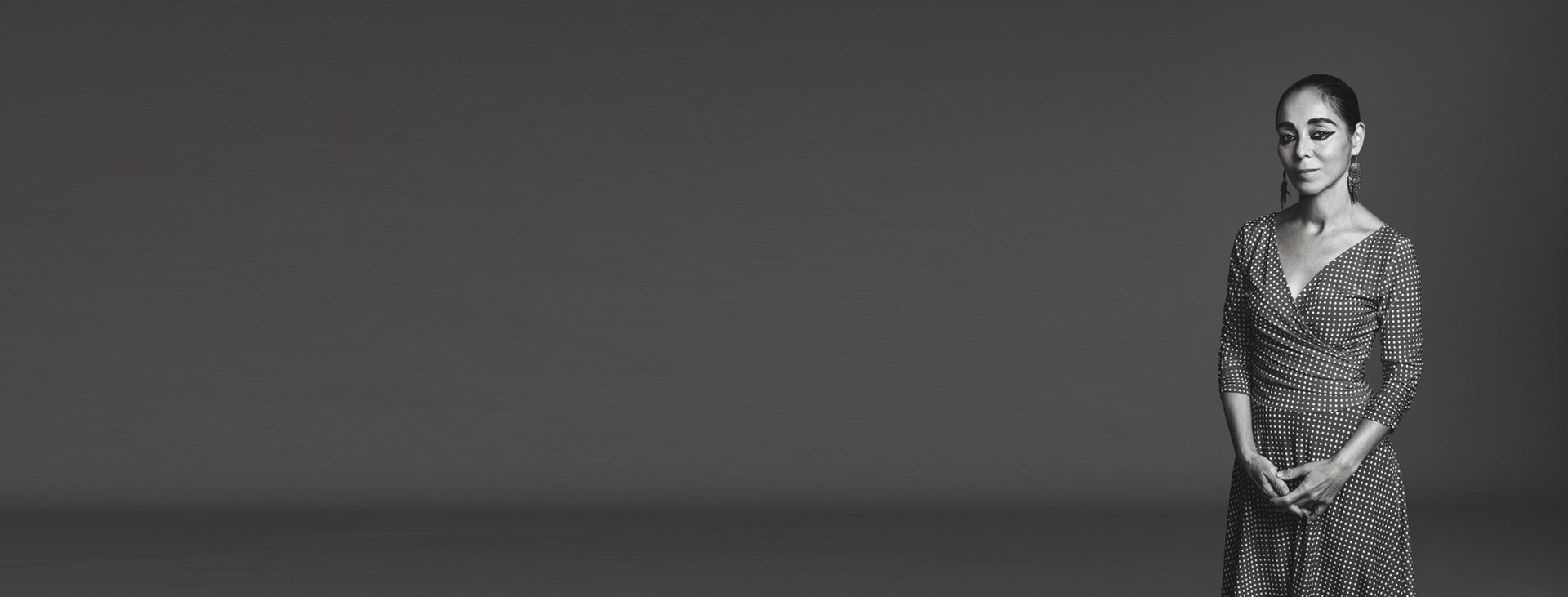

SHIRIN NESHAT One really critical experience was my Musée d’Art Contemporain de Montreal exhibition in 2001, which opened very soon after [the] September 11 [terrorist attacks]. Everybody thought they’d shut the show down because there was such strong anti-Muslim sentiment at the time. Even travelling to Montreal [by air] was a problem, so we drove. But the curator insisted on keeping the opening dates intact, and it was an unusually poignant experience. The audience that came was so large because everyone felt terribly sorry for the tragedy and for all the misperceptions that were happening around the Muslim community—so the art became a vehicle to tap into all these issues. But Montreal is actually quite a radical place. I think they would probably have cancelled it if it had been in the US.

JOANA VASCONCELOS I applied to the 2005 Venice Biennale with three pieces for the Arsenale and they were accepted. But in the process of organising the show, the curator Rosa Martínez called me and said, “I cannot have three works by you because there are too many artists, so you need to choose whether you want to have one piece at the entrance or two others inside the show.” That was a difficult moment, but I decided that I wanted to have the opening piece [A Noiva, a chandelier made of 25,000 tampons].

That was the best decision I ever made. I wasn’t known then. I was a young Portuguese artist and suddenly I was at the centre of this historic moment: the first Venice Biennale ever curated by a woman. When people approached the Arsenale, they saw my piece and understood that it set the stage for the entire show. If I hadn’t made that choice, I don’t think my career would have gone the same way. Even today, everyone says, “You’re the one with the chandelier of tampons!” So it’s still working for me.

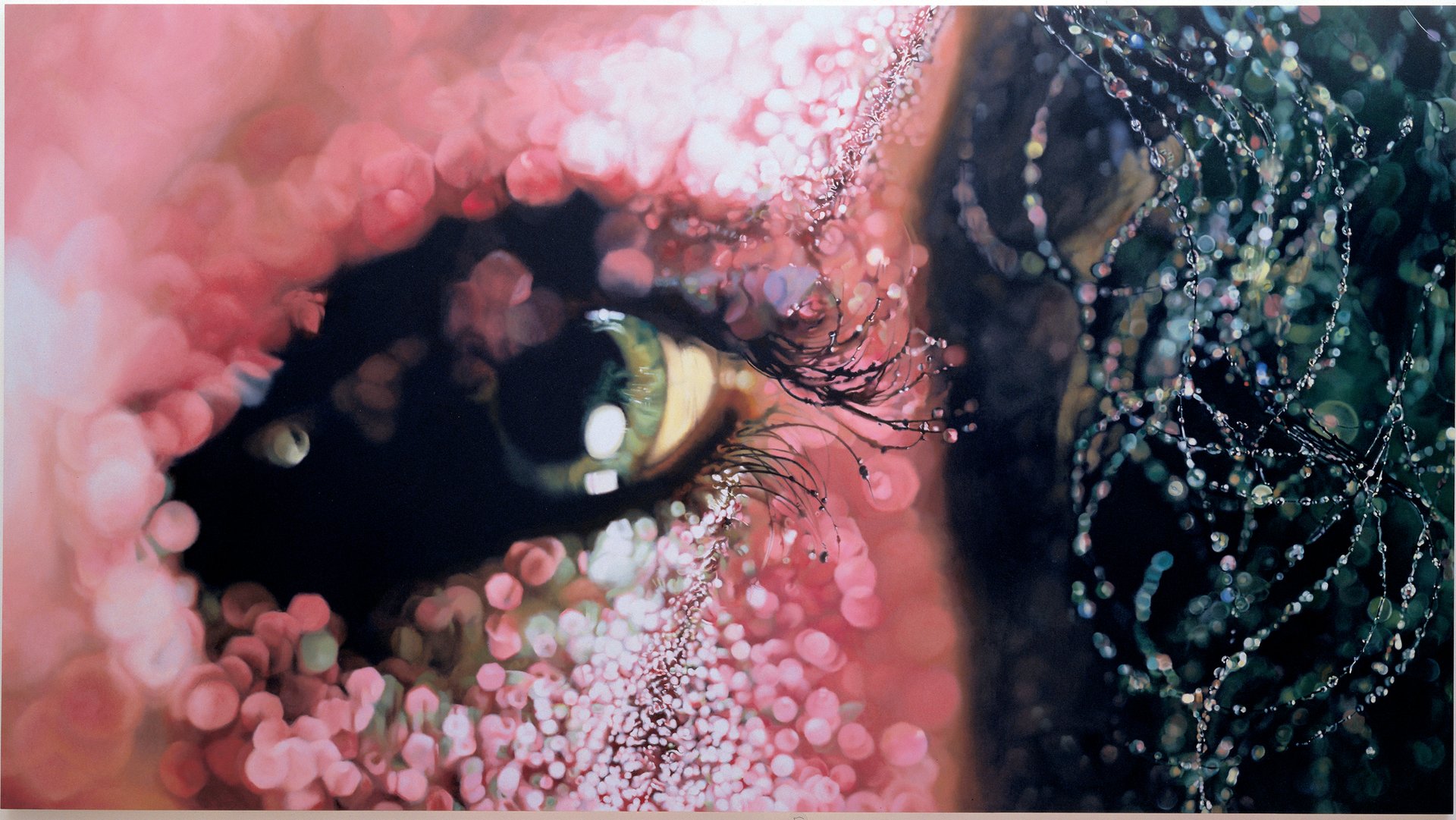

MARILYN MINTER My expectations for the 2006 Whitney Biennial were that I would have three paintings in the large group show. What actually happened was that they chose one of my paintings to be featured on the cover of the catalogue, they used another image to make banners for the show along Madison Avenue [in New York] and they used my paintings to advertise the show in all the promotional materials. It basically blew my mind to have all that exposure, and dramatically shifted the arc of my career. I went from being invisible to being the poster child for the biennial. I learned that public success changed my career, which shouldn’t be news to anyone. But I also realised that any artist who sticks around in the public awareness for more than 20 years usually has something unique to say. I used to not think that was true. Since then, I’ve become a lot more supportive of other artists and various career trajectories. What we do is so difficult, and staying relevant and true to one’s vision is a challenge.

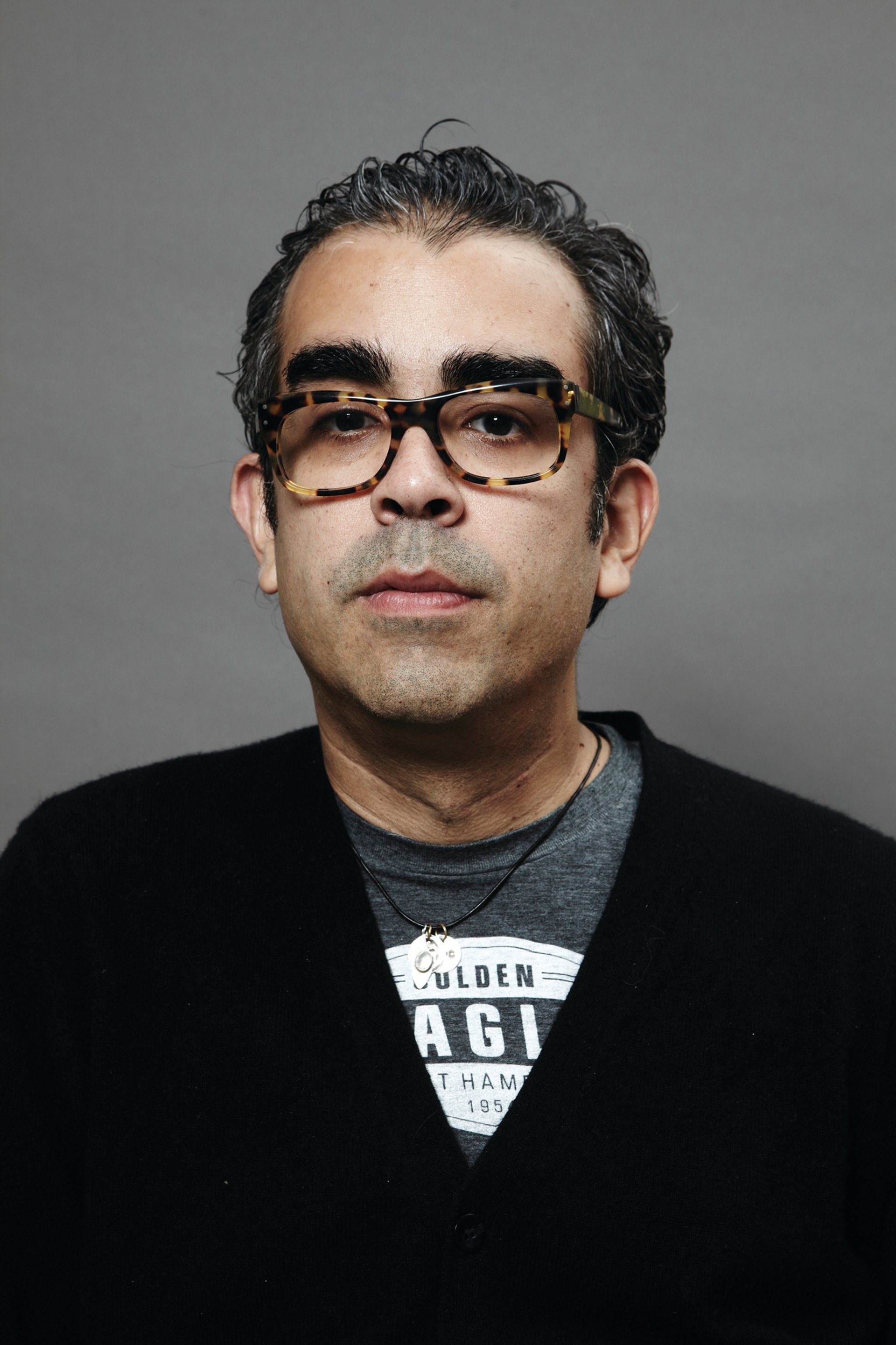

ENOC PEREZ My first solo show in a US museum, at the Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami in 2007, was important on many levels. I had never seen ten years’ worth of my work hanging in one place, and that was big because it made me realise that I had already proven with my work things that I thought I still had to prove. The question that brought to mind was, “Now what?” It had a profoundly liberating effect on me. I also had the notion that if your work got that kind of recognition, it would automatically lead to easy street. Wrong—the market only cares about the market. You may be cool today, and tomorrow, you’re just old. That’s life. Even with museums, [the fashion] can be painting now, performance tomorrow, and the next day, who knows? Me, I just keep working without expectations.

CHERYL DONEGAN With the New Museum show [Scenes and Commercials, until 10 April], I felt as though an incredible weight had been lifted from me. Given my experiments across media and my patchy New York exhibition history, with big gaps between shows, I feared that I appeared very inconsistent and somewhat incoherent to the audience in my home city. Working with Johanna Burton and her team at the New Museum changed all that for me. We were really able to trace a legacy of concerns and approaches within a diverse body of work and illustrate the through-lines. She and her fellow curators Sara O’Keeffe and Alicia Ritson really “got me” and helped me to articulate the consistency within the mobility of my practice. Even though the show is recent, I think it will help me a great deal in the future as, hopefully, I’ve had a chance to connect the dots. I feel very unburdened and confident that future work will be received against the backdrop that this show has provided.