“This little ass walking on two legs, wiser in his judgment than all mortals, nevertheless argues that there is no God.” It is difficult to imagine these words coming from a pope, yet this is the phrase Pope Pius II (1405-64) used to describe Sigismondo Malatesta (1417-68), the lord of Rimini, who is the subject of Anthony D’Elia’s Pagan Virtue in a Christian World.

D’Elia begins with a pivotal moment in Sigismondo’s life: his reverse-canonisation on 27 April 1462 by Pius. (It remains the only reverse canonisation in history.) Pius had already excommunicated Sigismondo on Christmas Day 1460, but had not achieved the desired result of having Sigismondo return his territories (which included Cesena, near Ravenna, and Fano, near Pesaro) to the Papal States. So in 1461, Pius sent an army to take them back. His expedition failed. Frustrated by his loss, Pius invented the reverse canonisation, whereby he could damn a living soul to hell.

The damnation was decreed with a papal bull and 39-page invective in which Sigismondo was accused of rape, incest, necrophilia, murder and pagan worship.

The text is graphic and vindictive. Pius demands that Sigismondo’s “spirit be damned and his cadaver abandoned without any funeral, images, praise or pomp; and that after being half burned on putrid wood his body should be torn apart and scorned by dogs and wild animals at night”. Yet Pius also claimed the reverse-canonisation was intended to spur Sigismondo into reformation, and in this he was successful. In 1463, Sigismondo—by then bankrupt and with few friends—surrendered.

He renounced his heretical beliefs, promised to recite the Creed every day, to fast on Fridays and to make pilgrimage to Rome and Jerusalem. He paid his overdue tributes to Pius and was allowed to remain lord of Rimini.

Early modern historians have traditionally propagated this “black legend” of Sigismondo’s crimes. By the 19th century, he had been turned into an Italian nationalist symbol of resistance against the papacy, eventually becoming a fascist hero in the 20th century. More recent scholars—D’Elia fits into this category—have tended away from the legend in favour of archival research.

D’Elia’s particular interest is in the revival of pagan themes in Sigismondo’s court, and he draws primarily from two works commissioned by Sigismondo: Hesperis, an epic poem by Basinio Basini of Parma imagining Sigismondo as classical warrior turned God, and Roberto Valturio’s treatise on war, where Sigismondo is depicted as the peer of classical figures such as Caesar and Alexander the Great. Both of these texts frequently praise the same traits that Pius condemns: craftiness, cruelty in war, a dedication to intellectual pursuits, a demi-god status, and the pleasures of erotic love.

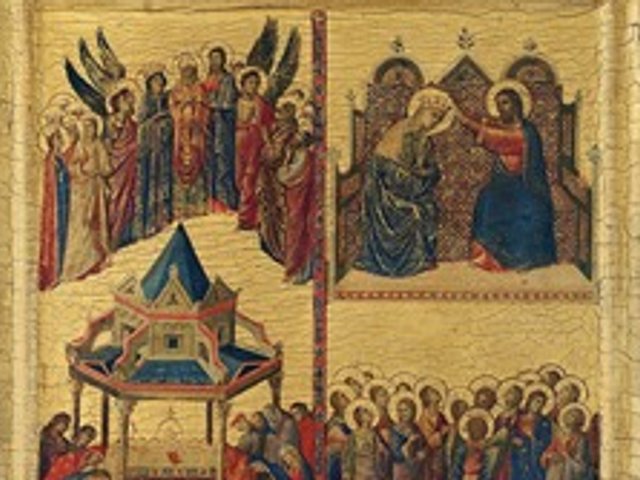

D’Elia only briefly mentions the artistic culture of Sigismondo’s court, which included paintings and bronze medals by Piero della Francesca and Matteo de’ Pasti. His largest commission was Leon Battista Alberti’s renovation of the church of San Francesco in Rimini, rechristened the Tempio Malatestiana. Sigismondo’s artistic patronage was born of his desire to outdo the great courts of Florence, Rome, Ferrara and Venice. Although individually, his artistic commissions are in line with the standards of his peers, as a whole, the artistic program is shockingly pagan.

Still, Sigismondo likely never considered himself a pagan in a literal sense. A true pagan would not have been fazed by the reverse-canonisation, but Sigismondo renounced all heresies to redeem his soul.

Despite his capitulation to Pius’s demands, Sigismondo would never give up his interest in the pagan world. In 1465 he interred the body of the pagan philosopher Gemistus Plethon in his Tempio Malatestiana. This proved that for Sigismondo, the clash between the pagan and Christian worlds was only political, not theological.

• Adrian Pobric holds an MA in Renaissance art from Syracuse University in Florence and is the assistant logistics director at the Heller Group

Pagan Virtue in a Christian World: Sigismondo Malatesta and the Italian Renaissance

Anthony F. D’Elia

Harvard University Press, 330pp, £29.95, €36, $39.95 (hb)