Günter Brus (born 1938) leaves little to the imagination. In 1968, he staged a performance at the University of Vienna with fellow artists Otto Mühl, Oswald Wiener, Franz Kaltenbäck and Peter Weibel: Brus cut his chest and thigh, smeared himself in excrement, drank his own urine and sang the Austrian national anthem while masturbating. He was promptly arrested and given a six-month prison sentence.

Brus was a founding member of Viennese Actionism—along with Mühl, Hermann Nitsch and Rudolf Schwarzkogler—a short-lived movement that shook up Austria’s conservative post-war society with extreme performances. The group’s objective was to break the dominion of abstract painting and to challenge the social structures that allowed Austria to suppress its Nazi past.

Brus’s performances routinely tested the patience of the Austrian authorities—the Actionists were often fined and prosecuted—and took a toll on his body. In 1970 he performed Zereißprobe (endurance test), in which he cut himself repeatedly with a razor blade. It was by far his most brutal performance and was also his last.

Since then, he has been working on drawing, poetry, writing—culminating in the book Irrwisch—and theatre pieces. Although Actionism has yet to be graced with a major international survey, institutions are increasingly taking notice. We caught up with the Graz-based artist as his retrospective opened at the Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin this week (until 6 June).

The Art Newspaper: What can we expect from your show at Martin Gropius Bau?

Günter Brus: The show is roughly chronological, but the Actionist works are not as numerous as the later works. It starts with my very early Informel Drawings, followed by my Self-Paintings, my book Irrwisch—the manuscript of which is on show in its entirety—and my later drawings.

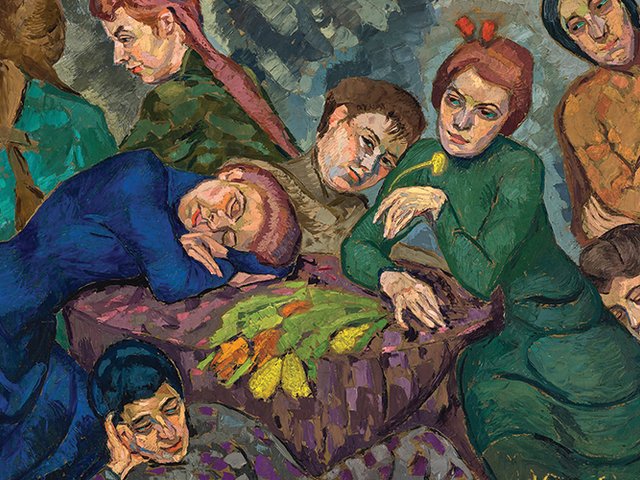

Your works are also currently on show at the Museum of Modern Art Vienna, in an exhibition that juxtaposes Viennese Actionism with the Austrian Expressionists, Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka (until 16 May). Did these artists influence you?

Actionism was somewhat different to other movements, such as Fluxus in Germany or the happenings in the US, because they didn’t really rely on their precursors as much as we did. In Vienna we always referred to those four artists—Richard Gerstl also belongs to that group even though he is seldom mentioned because he is less known internationally—and they certainly aroused our interest. What inspired us was mainly the way they treated the body, but also the similarities in the social structures from which they emerged. Vienna in the 1950s and 1960s faced similar repressions as it did at the turn of the century. Not for nothing did Sigmund Freud start working in this general time of upheaval in Vienna. We suffered a similar fate as Schiele, Klimt, Kokoschka and Gerstl.

In contrast to the other Actionists, you used your own body in your performances. Why?

Bringing my own body into play is indeed something that distinguished me from the others. The progression was from the canvas onto the body, to understand painting as an artist, so to speak, and not just as a tool. And because I was dissatisfied with showing art in the studio, I also brought it to the streets through my Wiener Spaziergang [Vienna Walk, 1965]. There were a few exceptions: I included my wife, Anni, in a few actions and my daughter, Diana, as a baby.

Some of your actions were very brutal. How do you feel when you look back at them?

It all seems like the Stone Age now; it was a long time ago. I still stand by my performances today. And there appears to be more of a vogue for Actionism now, interest has clearly grown in the past two to three years. I remember lots of negative comments in the past, especially in Germany. All four of us [Brus, Nitsch, Mühl, Schwarzkogler] were thrown into one pot—blood, urine, and excrement. This is no longer the case; we are seen in a more differentiated manner.

Some say that you would have been teetering on the edge of suicide if you had taken the action Zereißprobe (endurance test) any further. Do you agree?

I couldn’t sustain these heavy injuries any more. My actions weren’t theatrical like Nitsch’s or Mühl’s; they related to me and I couldn’t continue this self-harm forever. Zereissprobe was hard enough. It was my last action and I subsequently moved to Berlin, so automatically I got further and further away from Actionism.

Oskar Kokoschka died in 1980. Did you get a chance to meet him?

Yes, I met him at an exhibition opening; we shook hands. He asked me what I did and I told him that I was a student at the Academy of Applied Arts in Vienna and that I’ve been drawing a lot. He said that’s great, “but don’t you dare turn abstract on me!” Kokoschka was strongly opposed to abstraction, especially artists like Paul Klee. He was just very stubborn in this respect.

Who is carrying on the Actionism legacy?

Nobody really, because there is no reason for such performances. But in the East, particularly in Russia, where society is under pressure, there are some similar developments. Performances happened under pressure back in our time too. In a sense, these Russian performance artists are our successors because they are very well informed and interested in Actionism, but they also represent a movement that transcends ordinary art.

• Günter Brus, Zones of Disruption, Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, until 16 May

• Body, Psyche and Taboo: Vienna Actionism and Early Vienna Modernism, Mumok, Vienna, until 16 May