The tradition of artists assisting other artists is as old as the profession itself. Luxembourg & Dayan gallery has also made it the subject of an exhibition in New York, In the Making (until 16 April). Five of the artists included in the show spoke to The Art Newspaper about their experiences assisting fellow artists Andy Warhol, Jack Goldstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Gober and Ross Bleckner, and how it shaped their own work.

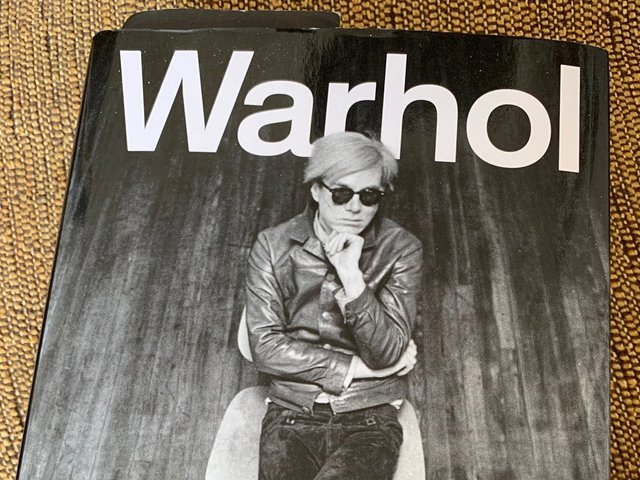

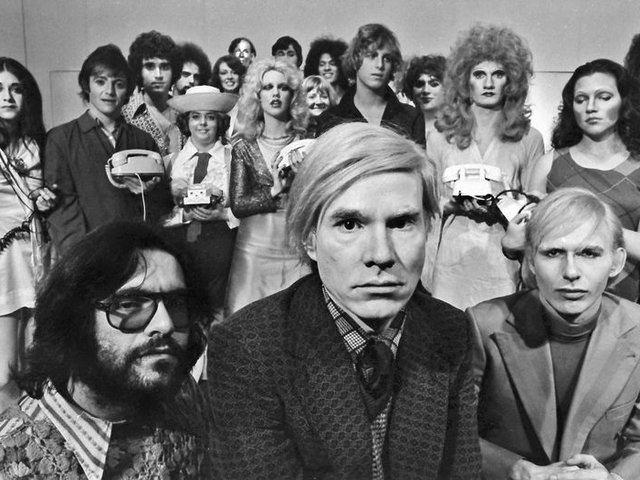

George Condo, assistant to Andy Warhol, 1980-81 What kind of work did you do for Warhol?

At a time when I was wondering, “OK, what should I do with my life?”, a position came along through an agency to work in a strange gallery that represented Andy’s master printer. The two of them were doing a show together and the dealer asked, “Anyone in this place capable of writing a press release?”. I volunteered and when Andy read it, he said, “I want that person to come and write about everything that goes on at the factory.” So I took the job as a typist, which soon evolved into a production worker on the Myths series after restoring, in a rather minimal way, the print of Diana Ross. On the production line, I became “the diamond duster”.

I worked from 10am until midnight. Andy would call in the colours on a red telephone that sat next to the silkscreen table and Horst Weber von Beeren and Rupert [Jansen] Smith would command the operation. We worked like slaves round the clock. There was no time off. The days went on and on until the smell of ink and screen cleaner made it impossible to breathe. We threw thousands of Warhols into the dumpster every night—most likely billions of dollars of Warhol prints that had been rejected, and rightly so.

Did you print the Warhol Myth work in the In the Making show?

Yes, dear, I did! I did all the diamond dust, everything. That piece haunted me for so long that it came back in a series I did in 1997 and 1998, which I’m going to show as a way to illustrate the aftershock of being a young apprentice for a great master, and of course how I learned my craft from Andy.

Ashley Bickerton, assistant to Jack Goldstein, 1982-86 You’ve described Goldstein as a “complicated and challenging personality”. How did that play out in the studio?

I was hired as someone to merely lay the images out at scale on the large canvases he set up, usually black back then. My job was to be faceless and not leave any trail of personality or even humanity, if that were possible.

With two oversized personalities in one studio, out in the wastes of Brooklyn, it did not take long before we clashed… as the years rolled on and more of his pharmacological adventures got mixed up in the social equation, the relationship soured and, sadly, was positively toxic by the end. He’s a rough and exhilarating train to ride and I held on as long as I could, but eventually I had to erect walls simply in order to function there. He was crushing himself under the weight of his dependencies and his all-encompassing bitterness.

Did working with Goldstein influence your own practice?

Jack was a massive influence on me. I probably learned more there than I learned at both CalArts and the Whitney [Independent Study] Program combined. It allowed me to see everything that had until then only lived as theory, as real living forms and languages. On the darker side, his relentless embitterment and jealousy left me with an unbending lifelong desire to stay optimistic and unaffected by the vagaries and venality of the larger art world.

Dorothea Rockburne, assistant to Robert Rauschenberg, 1963-68 How did you become Rauschenberg’s assistant?

We had all been good friends at Black Mountain College: me, Cy Twombly and Bob Rauschenberg, and it was not “Bob Rauschenberg” in big letters then. By the time I came to New York, in 1954, Bob had become very famous. One day, he ran into me on the street and we discussed my coming to work for him, which I was not very enthusiastic about doing because I didn’t want a job where I’d take the problems home at night. But I agreed to come for three or six months, and I ended up being there for five years. Bob was just a beautiful man and every day was a party.

Within a very short amount of time I seemed to be running the place. Maybe a year in, he asked if I knew somebody to help as a studio assistant. I ran into Brice Marden at an opening and he asked me if I knew of any jobs, and I said “yes!”. Both Brice and I were classically introverted artists and Bob is extroverted, and there was something about the combination that was quite magical.

Later, in the 1970s, the painter Carroll Dunham became your assistant. How did that work out?

Yes, he was young, bright and brilliant. And very handsome. He looks like Jeremy Irons.

Banks Violette, assistant to Robert Gober, early 2000s What was Gober like as a man and an employer?

He’s a very quiet, private person, but also a deeply ethical human being. He cares about the people around him. There’s something potentially vulnerable about being in a position like that, where he could easily cast a shadow over you, but he was very good about not doing that. We really had a kind of quarantined relationship; it was a job, which I was grateful for. But he did come to a number of my shows.

Ryan Sullivan, assistant to Ross Bleckner, 2005-2008 In what ways has Bleckner’s work influenced your own?

The way Ross “builds” a painting through almost sculptural layers of paint and his innovative paint formulas has had a lasting impact on the way I make my work. [At Luxembourg & Dayan] I’m showing a piece that’s part of a new series, and a lot of the preliminary work that’s consumed my studio in the last few months has been finding the right material to use, because what I was looking for wasn’t available ready-made. And although I can’t say for sure, the materials that I use might not be as important to me if I hadn’t worked for someone who uses his materials so unconventionally.