Jean Dubuffet, in an interview in 1977, identified the main problem afflicting artists—which has grown only more pronounced since—as the muddling up of two quite separate functions: presenting and creating. “Creating is antisocial, swimming against the tide of what is already accepted and admired, but the whole business of presenting one’s work to the public is a highly social activity. And when you mix the two, you get something inferior, like a wine that’s been cut with a bit of this and a bit of that. Some artists get so completely caught up in the business of presenting their work that they become like stars—the very opposite of inventors.” How right he was, and how far from real invention are most of today’s fashionable art stars.

According to the blurb for Suzanne Hudson’s book Painting Now, painting is a perpetually expanding and evolving form of creative expression. Pretty well anything goes—chuck it all in, from cybernetics to the kitchen sink. Yes, we had the Kitchen Sink painters in the 1950s, but many people do not remember them, students will not have learnt about them, and although some might just remember colourful John Bratby, even fewer will recall his Cornflake, lavatory and chip-fryer period. Despite the internet, ignorance abounds.

Go beyond painting to “art” and you’ll find a terminally overused and debased catch-all term, taken to mean anything from experimental film-making and performance to lifestyle and interior decor. What’s needed is a new toughness of definition: a return to painting as the manual application of paint to a support, sculpture as the three-dimensional exploration of physical form, and printmaking as an original reproductive medium demanding technical expertise. Drawing feeds and cross-fertilises all three forms, but everything else should be relegated to a separate category of Any Other Business, from which it might emerge eventually if it manages to prove its worth.

It is depressing how old-fashioned and derivative most of the work illustrated in Hudson’s book appears to anyone with even a basic knowledge of art history. One of the dangers of throwing wide the boundaries is the creation of meaningless international “airport” art. It’s made on the wing, so to speak, while browsing the in-flight magazines, and succumbs instantly to marketplace orthodoxies. Insubstantial and inane because it is not rooted anywhere, it is designed to appeal to art advisers employed by the supremely wealthy, who can recognise a type if not an original work. This new Mannerism is without meaning or savour. The word “meaningful” has been done to death by lazy commentators and critics, yet full of meaning is what we want our painting to be, not some hip and happening sub-department of the fashion industry.

If conceptual art was pretty thin the first time round in the 1960s, it is even more stretched today, with its excitement and elasticity buried beneath a thick and glutinous layer of theory. Much of what currently passes for painting is a more or less elaborate form of interior decoration: nicely patterned floors or wall displays, applied art masquerading as something finer. As a result of what is glibly called “post-studio practice”, there are far too many commissioned, site-based, multimedia sideshows. While they might fall into the entertainment bracket, they have nothing to do with painting or sculpture.

A far more thought-provoking survey is Morgan Falconer’s Painting Beyond Pollock, though the author seems to think that painting is no longer the pre-eminent medium of art, just one among many; he also believes in an anti-art plague called Global Contemporary. A shame really, as he writes well, cites many a worthwhile quotation, and includes lots of good reproductions. In fact, his book is a useful primer provided you do not believe everything he says. It’s a kind of doubters’ manual, reprising the mid-20th century crisis in painting encapsulated by Barnett Newman’s famous observation: “In 1940, some of us woke up to find ourselves without hope—to find that painting did not really exist.” Of course, painting existed and continues triumphantly to do so, whoever may periodically doubt its relevance. Falconer takes us on an enjoyable switchback ride through the intervening years in a series of short sound-bite chapters.

He is adept at cross-references, links, parallels and other elucidations, and has a synoptic habit of mind. His book is a huge achievement, somewhat akin to Norbert Lynton’s Story of Modern Art (1980). One can criticise him for trying to represent all points of view equally, but he does have his own opinions. He prefers Richter’s use of photography to Bacon’s, finding the latter’s “less courageous”, and he blithely compares Freud and Annigoni, as if the heightened realism of one equated to the “icy classicism” of the other. Good, provocative stuff.

Inevitably, with such a huge span, Falconer falls into oversimplification from time to time. The CoBrA movement gets short shrift, but then most commentators tend to undervalue what was in effect Europe’s answer to American Abstract Expressionism. Falconer has now made his home in New York, which suggests where his sympathies lie. And he gives yet more credence to that most overrated of living painters, Gerhard Richter.

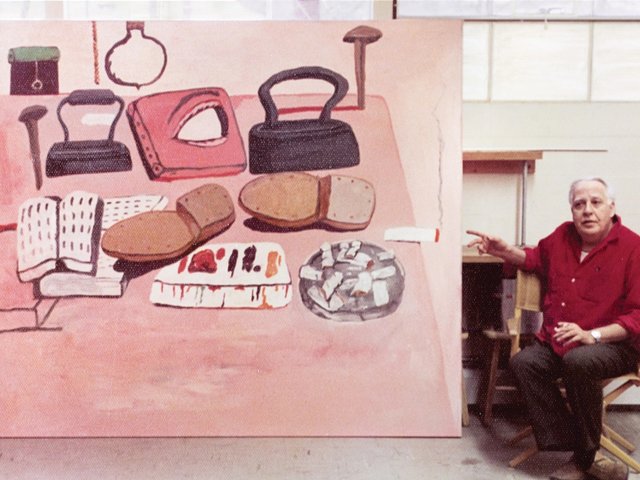

On the other hand, he comes out with such memorable phrases as “unfinished and enthralling endings” for what Pollock and his contemporaries created. Amazingly, there is no mention of Patrick Caulfield or R.B. Kitaj, though we get intriguing pairings: Guston and Baselitz, the awkward figuration of Eric Fischl and the plate-smashing theatricals of Julian Schnabel. The narrative speeds up as we approach the present, and the analysis (sadly) becomes more fleeting. Is this because the work discussed is of less value, or because we have so little historical perspective on it? A moot point.

White Cube staged a major painting show that ended early this year, curated by the American critic Barry Schwabsky. Tightrope Walk: Painted Images After Abstraction, the hardback catalogue accompanying the exhibition of the same title, contains much thought-provoking material, mostly in short declarative texts, arranged around Schwabsky’s central contention that the force of the image counts more than the recording of an appearance. Different versions of figuration from Bacon and Baselitz to Picasso, Morandi and Matisse were intriguingly juxtaposed on White Cube’s aircraft-hangar walls in Bermondsey, south London, with the likes of Cecily Brown, Patrick Caulfield, Alex Katz, Chris Ofili and Alice Neel. The joker in the pack was Jeffery Camp (born 1923) an artist that some of us have cherished for years, but Schwabsky discovered fairly recently and quite rightly feels the urge to celebrate.

Camp is the author of three books, two of them manuals of instruction—Draw (1981) and Paint (1986)—and a maverick memoir entitled Almanac (2010). He taught art for much of his life and decided to enshrine his beliefs in book form; being a natural independent, he offers a highly original approach to learning. His painting is equally unique: he is a London visionary of the parks and river, framing odd-shaped vignettes of great poignancy, finely drawn and feather-brushed with strong but subtle colour. Apparently Schwabsky could not believe how old Camp was (he’s 92)—on the evidence of the paintings he thought he was a young man. Let’s hope that Camp’s new admirers will appreciate that his lyrical visions are painted straight, with no fashionable irony intended.

Schwabsky took his title from Bacon: “This image is a kind of tightrope walk between what is called figurative painting and abstraction. It will go right out from abstraction, but will really have nothing to do with it.” Perhaps here is a clue. Does Camp’s painting of unashamedly abstract pictures when he is not being figurative somehow account for his enduring potency as an artist? Does the future for figuration lie in a new alliance with abstraction, a new understanding, and not the traditional (and inaccurate) hostility between the two? Revealingly, Schwabsky concentrates on the figure, not landscape, because landscape “is often already almost a kind of abstraction”. So perhaps a similar degree of abstraction needs to be imposed on the figure in some way to bring it into line? (Morandi: “Nothing can be more abstract, more unreal, than what we actually see.”) As our critic admits: “The ways of manifesting an image through painting are too numerous to be contained by a single exhibition and book.” Quite—hence the diversity of this roundup.

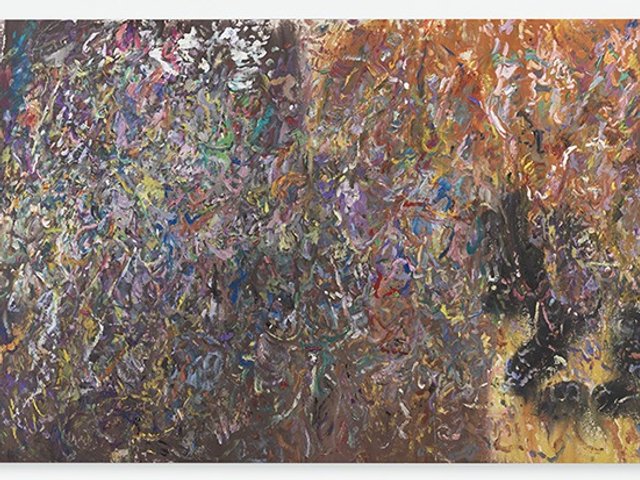

“Painting for me is a set of connections, a set of sensations of conflicting movements and experiences, which somehow, one hopes, has congealed or cohered or risen out of the battle into being an image that stands up for itself.” So says the title character of Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Painting, a beautifully produced novel-sized volume, which is more an extended meditation than an art book, though it does contain 100 illustrations. Its author Catherine Lampert, is a curator and art historian who has been sitting for Auerbach since 1978. She is one of the artist’s coterie of immensely loyal supporters (which includes the art critic William Feaver), whom he paints on a regular basis. What better way to get to know someone? Robert Hughes sat for his portrait (though only a drawing) when he wrote his marvellously perceptive monograph on Auerbach. Lampert has turned her long experience of the artist to good purpose: this is an enjoyable and informative book.

She traces Auerbach’s career with very specific and to-the-point descriptions of pictures and developments. We are reminded that Auerbach, like Sickert before him, worked as an actor early in life—perhaps essential training for all artists? It is good to know that he rates the work of Coldstream, Lowry and William Nicholson, and that he has a horror that art should grow respectable, democratic or therapeutic. He prefers that it should be “distrusted by all sensible orthodoxies and moralities, for who knows where it will lead?” This book is valuable, not least for the amount of contextual information it fields—more here than in any other I’ve read about him.

In 2001, Auerbach was asked what advice he would give a young artist starting out after art school. He said it was important to begin with “some experience that is your own and to try and record it in an idiom that is your own, and not to give a damn about what anybody else says to you... I think that the key word there is subject—find out what matters most to you and pursue it.” That he followed his own strictures may be judged from Frank Auerbach, the catalogue of the Tate exhibition (until 13 March), a handsome paperback publication, edited by Lampert. It consists of an essay by TJ Clark, a chronology and Lampert’s excellent 1978 interview with the artist, here usefully reprinted. Although Auerbach has been in the same studio for 60 years, and painting some of the same sitters for 40, the works illustrated are refreshingly strong in individuality, rather than chosen to tell the story of a career. However, as the artist himself observes, paintings need both unity and particularity. He has said: “I think all good painting looks as though the painting has escaped from the thicket of prepared positions and has entered some sort of freedom where it exists on its own, and by its own laws, and inexplicably has got free of all possible explanations. Possibly the explainers will catch up with it again, but never completely.”

Well, we can try.

• Andrew Lambirth is a freelance writer, critic and curator. He was the art critic of the Spectator from 2002 to 2014. His most recent book is on William Gear, the pioneering Scottish abstract painter and member of CoBrA (Sansom & Co, 2015)

Painting Now

Suzanne Hudson

Thames & Hudson, 216pp, £29.95 (hb)

Painting Beyond Pollock

Morgan Falconer

Phaidon, 384pp, £49.95 (hb)

Tightrope Walk: Painted Images After Abstraction

Barry Schwabsky

White Cube, 136pp, £20 (hb)

Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Painting

Catherine Lampert

Thames & Hudson, 240pp, £19.95 (hb)

Frank Auerbach

Catherine Lampert, ed

Tate Publishing, 176pp, £24.99 (pb)