The new organisation taking over provenance research into the Gurlitt hoard from a much-criticised taskforce promises to learn from past mistakes. “Our research will be sound, efficient and above all transparent,” says Uwe Schneede, a co-director of the Stiftung Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste (German Lost Art Foundation).

The foundation was established a year ago to be “the national and international contact partner for all matters pertaining to the illegal seizure of cultural assets in Germany in the 20th century”.

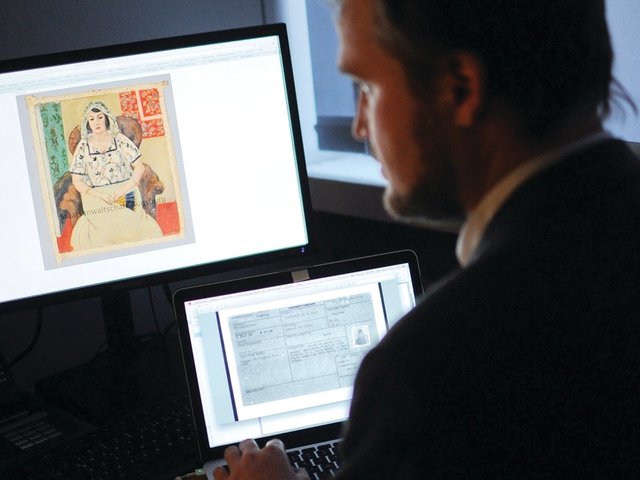

It will take over from the Taskforce Schwabinger Kunstfund (Schwabing art trove taskforce), which was established to research the provenance of the Gurlitt troves of around 1,500 works seized in February 2012 in Munich and in February 2014 in Salzburg. It included representatives of organisations involved in research and restitution issues, as well as experts. Its head, Ingeborg Berggreen-Merkel, a lawyer and politician, was initially confident that work on provenance documents of around 500 works in the Gurlitt troves would be “largely accomplished” before the end of 2015. Its slow progress led to a barrage of criticism, and, at the end of November, Berggreen-Merkel admitted that the job was “far from being finished”. To date, only five works have been clearly identified as looted art, and more than 100 claims are waiting to be processed.

Schneede defended the taskforce saying: “Research has been done consistently and professionally. But unfortunately people often confuse research work with restitution.”

Alfred Weidinger, an expert on restitution issues who has been highly critical of the German-Swiss agreement on the Gurlitt bequest and how the German authorities have dealt with the issue, says that the work of a research team on provenance is very complex. “If it is driven by ethics, it cannot have an expiry date, because you will want to have the same commitment to the investigations into a Matisse worth €12m as a lithograph worth €200. But the problem is that the main part of the works in the Gurlitt hoard are graphic works, not major paintings,” Weidinger says. “So Berlin and Bern will have to make up their minds about how to proceed”.

Meanwhile, Ute Werner, a cousin of Cornelius Gurlitt, is challenging the last will, which bequeathed the whole collection to the Kunstmuseum Bern. A Munich court is expected to announce its verdict on this challenge shortly, as the deadline for objections to the new expertise on Cornelius Gurlitt’s testamentary capacity, commissioned by the Court and handed out to the parties at the end of 2015, is the beginning of February. Both the German government and the Kunstmuseum Bern have announced a planned exhibition of works from the hoard, presumably before the end of 2016. But this will depend on the outcome of Werner’s claim.