In the history of religious painting, depicting heaven posed a problem. As artists began to place increasing value upon naturalism in the 15th century, they were challenged to make the invisible visible as well as believable. Christian literature often describes the appearance of heavenly figures on earth with the sudden arrival of clouds, and because those clouds offered artists something tangible to paint, they were quickly adapted as symbols for heaven. The great variation in cloud types (wispy cirrus clouds, variegated altocumulus clouds or dense, fluffy cumulus clouds) gave artists numerous opportunities for innovation.

The representation of heavenly cloud formations is generally said to have reached its apotheosis in Baroque ceiling painting. Most scholars trace this development to Correggio and his early 17th-century Roman followers, but in The Spectacle of Clouds, 1439-1650 Buccheri presents a convincing argument that theatre was the more important influence. Her interdisciplinary approach, which is becoming more prevalent in Early Modern studies, offers a wealth of new connections between the visual and performing arts.

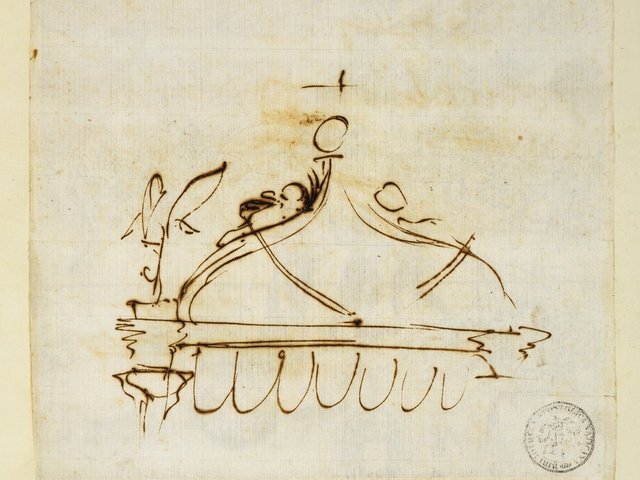

Buccheri begins with Medieval mystery plays, which often included cloud machinery as part of the set design. The machinery—wood-and-iron structures concealed in cotton to provide a cloud-like softness—transported actors from heaven to earth. In an annunciation scene, for example, the angel Gabriel would appear to descend atop a floating cloud. These machines became increasingly complex with the introduction of the mandorla, an almond-shaped ring of lamps surrounding an actor that could be ignited via a hidden foot pedal.

Between 1420 and 1430, theatre designers working in churches began to build multiple platforms, each of which moved independently. Heavenly choirs and God would be represented on various layers of moving clouds, while angel messengers could descend separately from a church’s dome to the stage below. Buccheri sees a direct translation of this design in paintings such as Francesco Botticini’s Assumption of the Virgin (1475-76), in which Mary, released from her grave, ascends towards the dome atop a single floating cloud.

Buccheri shows that once painters fully grasped the visual language of theatre, artists such as Correggio could construct complete spaces out of clouds, without reference to theatrical structures. But his innovation brought with it the problem of illegibility. Correggio could cover the sides of the dome in a convincing cloudscape, but the most important figures were left to the centre of the dome, their heads obscured by the soles of their feet.

Buccheri examines the various solutions developed by his followers and she sees Giovanni da San Giovanni’s Glory of Saints (1623) in the Basilica dei Santi Quattro Coronati in Rome as the best answer. Giovanni achieves the difficult balance of clarity and naturalistic foreshortening. Buccheri highlights the influence of complex stage design here, where figures from multiple cloud zones interact, and some cloud layers in the centre appear to be rising towards God.

The essential problem with the study of Renaissance and Baroque theatre is that no one can see the plays, set designs and costumes. It is no small task for Buccheri to argue the importance of theatre on an entire visual tradition without being sure exactly what the performances looked like. Buccheri is transparent about these issues throughout her study and has taken time to piece together contemporary drawings, eyewitness accounts and texts of the plays. One of the most elaborate plays she describes, La Pellegrina, performed at the Uffizi in 1586, had a cast of nearly 100 actors with 286 costumes, live music, light effects and the first ever moving stage. Yet we cannot fully picture this tremendous spectacle as it once existed. Buccheri’s convincing connections between these performances and paintings bring these plays to life again, even if only in part.

• Adrian Pobric holds an MA in Renaissance art from Syracuse University in Florence and is the assistant logistics director at the Heller Group

The Spectacle of Clouds, 1439-1650: Italian Art and Theatre

Alessandra Buccheri

Ashgate, 216pp, £65, $105 (hb)