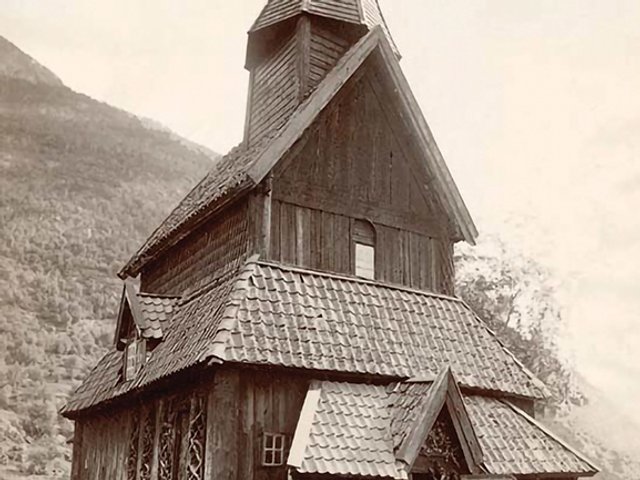

“What’s the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without any pictures or conversations?”. One might equally suggest that a book on architecture, whether its subject be Palladio or Corbusier, completely lacking in plans, sections or perspectives is an oddity. A few period images apart, however, Elain Harwood’s massive, somewhat unwieldy, Space, Hope and Brutalism is instead illustrated throughout with new colour photographs—of excellent quality, generally taken in bright sunlight and blue skies—by James Davies. They are in tune with the author’s highly positive, indeed enthusiastic, account of the “heroic” era of architecture that followed the end of the Second World War.

Several decades in the making, the book draws heavily on Harwood’s work as an investigator and historian for Historic England (latterly English Heritage), hence the focus on England rather than Britain as a whole. Organised thematically by building type, the text is a work of enormous erudition, setting the architectural scene in a context of political, social and economic history. (Facts abound: police numbers increased by 40% between 1951 and 1972; 10,000 primary schools were built between 1945 and 1973; 300 new public libraries were built between 1960 and 1965.) A biographical index of architects is a valuable addendum. In short, the book is set to become a standard work of reference for any student of its subject.

Brutalism, which currently seems to be in fashion, features in the book’s title, but is only one strand in the story. The Brutalists, with the critic Reyner Banham as their scribe, loathed the “soft” Modernism represented by the 1951 Festival of Britain. Harwood is judicious, seeing the virtues not only of the Festival Hall, Lasdun, Stirling and Seifert, but equally of traditionalists such as Raymond Erith, Vincent Harris and Donald McMorran. Readers of The Art Newspaper will find the contribution of artists—Piper, Sutherland, Moore, Pasmore, Bawden, Hepworth and many others—to the making of buildings well documented. Even the Shell Centre, a project critically lambasted, generated a remarkable number of commissions to artists and designers.

Not everyone will agree with Harwood’s claim that “the architecture of the past 60 years is as valuable as any in our heritage”, but she has provided a phenomenal corpus of information that is certain to inform ongoing debate. This is not a book to sit down and read: the thematic progress through schools and hospitals, offices and art galleries and so on quickly becomes wearisome. There is barely a hint of the public revolt against Modernist architecture and planning that came to a head in the 1970s. The problems affecting the mass social housing projects of the post-war period, for example, do not figure. As for Alice’s “conversations”, there is little evidence here of the experience of owners, occupants and users. The post-war heritage deserves to be recorded and much of it needs Harwood’s admirable championing. We cannot afford to randomly jettison it. But we also need to recognise the scale of the challenge involved in adapting it to the needs of the 21st century.

• Kenneth Powell is an architectural historian, critic and consultant. He is a member of the London Diocesan Advisory Committee and an Honorary Fellow of the RIBA

Space, Hope and Brutalism: English Architecture 1945-1975

Elain Harwood, photographs by James Davies

Yale University Press, 736pp, £50 (hb)