From the standpoint of Havana, just 90 miles south of the US coast, Miami is the forbidden city. But with the world’s largest community of Cuban émigrés, Miami has cultivated a unique appetite for supporting the island nation’s art—long before the loosening of travel and trade restrictions this year made that easier. The ties that link the two countries have never been more evident than in a series of exhibitions on Cuban artists around Miami, programmed ahead of the news that diplomatic relations between the US and Cuba would be restored.

Although she started collecting art in the 1970s, Ella Fontanals Cisneros has focused on Cuban art for the past five years. She stumbled upon a “distinctive abstract painting” in Havana and “bought it immediately, without even asking who the author was, due to the magnetism it exerted”, she writes in a catalogue essay for the current show at the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (Cifo). Shortly after, similar work appeared in an auction and she asked the artist’s name: Gustavo Pérez Monzón. A participant in the groundbreaking Volumen Uno show in Havana in 1981, Pérez Monzón is part of the 1980s generation of Cuban artists—the first to grow up under Castro.

The current exhibition at Cifo includes the artist’s mixed-media cardboard compositions, which combine geometric abstraction with Abstract Expressionism, and which explore his interest in mathematics, logistics, numerology and “spatialism”. In the catalogue, the artist cites Mark Rothko, Richard Long, Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt as important influences, and, “above all, the intellectual component that conceptualism introduced into art”. But after a prolific decade making art in Cuba, Pérez Monzón stopped producing in the 1990s and moved abroad. Undeterred, Fontanals Cisneros began to search Havana for his art. The survey show, which includes nearly 70 of his works from 1979 to the late 1980s, was presented during this year’s Havana Biennial at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, before coming to Cifo in Miami (Gustavo Pérez Monzón: Tramas, until 1 May 2016).

Meanwhile, another Cuban émigré, Carlos Estevez, who left Cuba in 2003 and now lives in Miami, has a large solo show at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum (until 3 January 2016). The display of 35 works dating from 1997 to the present day—mainly works on paper, many of which also feature writing by the artist, as well as sculptures and assemblages—includes some of “his most personal works”, says Klaudio Rodriguez, the museum’s curator.

The title piece, Celestial Traveler (2014), is an ornate 6ft-long kite. It’s a metaphor “for my personal voyage”, the artist says. Estevez is known for creating visual metaphors, and says the work recaptures a childhood memory. “A kite is something of yours lifted in the sky,” he explains. “Metaphorically, you make a celestial connection: you are seeing yourself from above and you are also able to see the world from above.” This sense of perspective is vital to Estevez. “Life in Cuba was very isolated,” he says. “People were obsessed with the idea of travelling.”

Another work, Botellas al Mar (bottles in the ocean, 2000), was inspired by a walk along El Malecón, Havana’s famous five-mile-long sea wall, while the artist thought about his mother, who lived in Miami. “There is a tremendous abyss between Cuba and Miami: so close, and yet so far away,” he says. He decided to fill bottles with drawings that could be thrown into the sea and found by others. The works made their debut at the 2000 Havana Biennial, but at the Frost museum, 82 of the glass bottles are displayed alongside their corresponding drawings on large vertical sheets of paper. “People often gravitate to [these works],” says the museum’s director, Jordana Pomeroy.

This period also witnessed a generation of artists thriving outside Cuba. The De la Cruz Collection has three Cuban-born artists—Ana Mendieta, Félix González-Torres and Jorge Pardo—in its survey show You’ve Got to Know the Rules to Break Them (until 12 November 2016), which juxtaposes “new American painting with German Neo-Expressionism”.

Among the estimated 125,000 Cubans who left the country during the 1980 Mariel Boatlift was Carlos Alfonzo, who became an influential figure in Miami’s art scene in the 1980s, says César Trasobares, the curator of Carlos Alfonzo: Clay Works and Painted Ceramics (until 24 April 2016) at the Pérez Art Museum Miami. More than 70 works in clay have been brought together to mark the 25th anniversary of Alfonzo’s death due to Aids-related complications in 1991. “For Alfonzo, works in clay and ceramic were an integral part of his evolving pictorial expression,” Trasobares says. “Alfonzo studied Picasso’s and Miró’s ceramic works and considered them precedents to emulate.”

The exhibition features small drawings, paintings and bold works in clay, influenced by the Cuban avant-garde, many involving the artist’s regular motifs—a pierced tongue, wounded hands, a listening ear, a stabbed arm, a grinning mouth.

The highlights include studies for two large public art murals in Miami, including the glazed clay mosaic Ceremony of the Tropics (1986), which was commissioned by Miami-Dade Art in Public Places. “Ostensibly a scene of picking fruit, Ceremony is a visual puzzle, the grout so thick between the tiles that its grid must be penetrated, the iconography so sophisticated that it must be revealed,” wrote the art critic Helen Kohen in a review in the Miami Herald at the time. “Those ears of corn are stand-ins for gaping mouths; his watermelons become eyes and a cup is a mask.” The work can still be seen at Miami’s Santa Clara Metrorail Station, in the city’s wholesale fruit district.

• Art Basel Salon, New Role for Art in Cuba, Miami Beach Convention Center, Thursday 3 December, 6pm-7pm

Cuban art at the fair

• Interest in Ana Mendieta’s films is spreading like wildfire after a filmography of 104 works—a collaboration between the Estate of Ana Mendieta and the University of Minnesota—was published in September. Two super-8mm short films, Volcan (1979) and Silueta Sangrieta (1975), were transferred to high definition for a show in Minnesota and can be seen at Galerie Lelong’s stand (G1) this week. The gallery is also showing works from the 1970s to the 1990s by Zilia Sánchez, as part of the fair’s Kabinett sector.

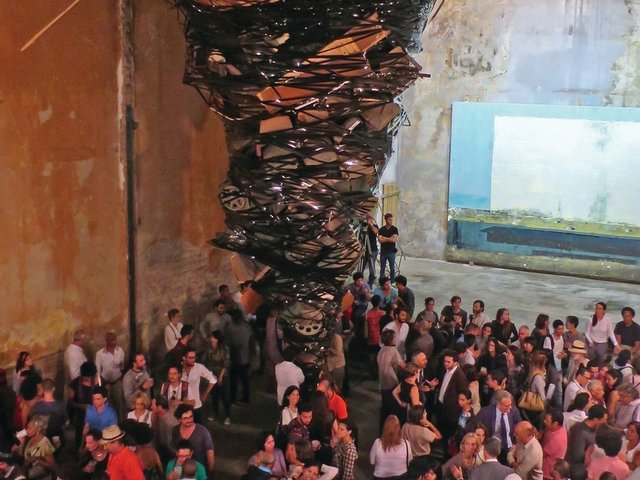

• The Havana-based artist Carlos Garaicoa is best known for architectural models, photographs of abandoned sites in Havana and architectural and public interventions in urban spaces. His sculpture Deleuze & Guattari Fixing the Rhizome (2008) is on show at Galeria Continua’s stand (L6).

• Petzel Gallery (K17) is bringing a new work by Jorge Pardo, based on a self-portrait in which he glides down a red water slide into a pool. The panels were etched using a computer-controlled mill, and a built-in iPad Mini enables you to chat to the artist via Skype.

• Three watercolours and a sculpture by the artist collective Los Carpinteros are on show with Sean Kelly gallery (B17).

• Work by Cuban artists can also be found at Fredric Snitzer (showing Alexandre Arrechea, José Bedia, Maria Martinez-Cañas and Rafael Domenech; B14), Mai 36 Galerie (Michel Pérez Pollo, Raúl Cordero and Flavio Garciandía; L4) and Jack Shainman Gallery (Yoan Capote; B21).