THE INQUISITOR

Helena Kennedy

Human rights lawyer and member of the House of Lords

THE WITNESSES

John Barrow

Professor of mathematical sciences, cosmologist and playwright

The reason for the links between maths and art is clear; a good and simple definition of mathematics is that it is just the collection of all possible patterns, and within that superset of all possibilities lie all the things that people draw and find appealing—things that people design, sculpt and so on. But this is a very weak definition. Anything permits a mathematical description by that rule, and sometimes those patterns are neither useful nor interesting.

Sometimes maths sheds light on art, but sometimes art teaches mathematicians something new or brings something unexpectedly into the light. We all appreciate Escher’s wonderful drawings, the tiling on Islamic buildings, Jackson Pollock’s intuitive discovery of the self-similarity of fractal design and painting. The way that you can produce curves that are optimally smooth or unusually jagged is something that we have come to call critical phenomena. All these focus a searchlight on the world of art, but they also allow scientists to look in the world of art for examples that are elegant and beautiful and dynamic. Scientists, particularly particle physicists, have often talked about beauty in their equations or in their theories. But it is an odd type of beauty. It is pure symmetry and, from Plato to Kant to modern times, art theorists have emphasised that artistic beauty is not to be associated solely with symmetry; there needs to be some deviation from it, some strangeness in the proportions, something unexpected and interesting.

Science is a two-fold activity. The first part has no rules. You can invent theories in any way you like: reading tea leaves, looking at the stars, dreaming. But then there’s a very rigorous process by which you test those theories to see if they are right or wrong. Art is often advertised as having no rules at all so it does not have the second stage. But it’s not really like that. The world of art likes to invent its own rules: rectangular canvases, watercolour paints, work in alabaster, drawing with silver point and so on. Why do these self-imposed challenges become forced on our creativity?

Many aspects of art bear witness to our evolutionary history; we like some things because once upon a time an affinity for the symmetry they display, the landscapes they picture or the information that they provide would have been life supporting, and a by-product of our sensitivity to these life-supporting environments has informed and fashioned much of our art appreciation today.

At the end of the 1970s, small computers with easy interactivity and good graphics enabled individuals to produce inventive artistic work of a particular type of algorithmic style. And what was discovered in the study of that type of calculus of intricacy was eventually something that, I think, is a lesson for all types of artistic appreciation. We discovered that there were certain types of complexity. The falling of grains of sand to make a pile have an odd property: the grains fall on the pile and, as they pass through it and drop to the side, new ones come along. The overall pattern of the pile remains organised and the same but each sand grain passes through in a chaotically unpredictable career down the side of the pile. When the pile is in its stable, pyramid-like, straight shape it is the most sensitive to small changes from the incoming grains but retains the same overall pattern.

Many works of art, whether visual art, music, sculpture or drama, have this critical property that if you make even small changes to them you look at them in a different way. Art draws out this unpredictable richness of human experience; it is something that is necessary to enlarge and keep enlarging the human imagination.

Q Why is it that the sciences have not been exposed to the same kind of a commodification as art?

A People regard themselves as a single discipline—say, studying the nature of stars—so it is regarded as improper that there should be any proprietorial aspect to it. For example, there is no copyright on astronomical images taken by telescopes.

Karen Armstrong

Former nun, now a broadcaster and writer on religion

First, art gives us meaning. We are meaning-seeking creatures. We fall very easily into despair if we cannot find some meaning or value in what we are doing and this can be very dangerous in society. Forensic psychiatrists have interviewed all the people involved in the 9/11 plot and in the subsequent lone-wolf attacks, and have found that Islam is not really the cause. By far the biggest cause that propels people to the battlefield or to these appalling actions has been a sense of futility, despair, lack of meaning and triviality.

So from the very beginning, human beings started to create religions at the same time as they created works of art.

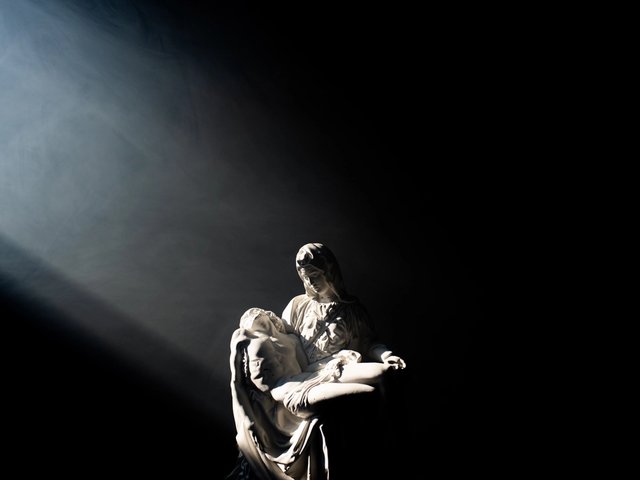

In the caves of Lascaux and Altamira, we see the co-inherence of religion and art. Those numinous depictions of animals that the artist must have painted by the aid of flickering lamps were clearly the product of a deep imperative. We don’t know what these paintings were aiming to do. It’s tempting, however, to see them in the light of some of the indigenous hunting peoples of today, who are often profoundly disturbed that they have to kill the animals whom they regard as friends, patrons and whom they honour, and they go to extraordinary lengths to come to terms with this.

Art helps us, or should help us, just as religion should help us, not to answer the questions “Why death?” or “What happens after?” but to live intensely while reminding ourselves that we are mortal. Today we have a culture of denial; we want to push death away but that means we are siphoning off a major part of our nature, which is our mortality.

Second, art helps make a place for the other in our minds. When we look at a great work of art we’re entering into the unique viewpoint of another human being that is normally hidden from us. This is essential for a culture. Unless we now learn to find out what other peoples around the globe are really thinking and feeling, the world is not going to be a viable place.

Finally, art should hold us in an attitude of awe and wonder. The poet Wordsworth talks about “spots of time”, moments in our lives when various currents come together with a sense of intensity. We look at a painting, we see a pair of rough peasant’s boots and a chair that suddenly seem to become numinous and significant, and this affects the way we look at life outside the work of art in the real phenomenal world. This, again, is essential for our culture.

Art can help us to hold the universe and everything and everybody in it as a revelation of an utterly mysterious world so that we treat everything and everybody with reverence. Unless we cultivate this, I doubt that we’ll have a viable world.

Q Why have these people, who have turned to a fundamentalist notion of Islam to give meaning to their lives, become so destructive of art?

A I think a profound insecurity, a deep sense of ego, is involved. Ego is always the great trap of art and religion. People think that their view of the divine is the only one and so they feel personally threatened by any rivals’ views.

Ben Okri

Poet and Booker Prize-winning novelist

We DEFINE art in relation to ourselves, our groups, our tribes, our race, our ideology, our religion, our politics, our limitations. But art is always greater than these limitations. It would seem to me to be the expression of the soul against the limitations of the mind. It is always rebellious. It always rebels against boundaries. Its first rebellion is against function and use. That is probably why our distant ancestors always made their art out of useless things; they beautified stone, wood, and later they beautified gold. But they made beauty out of what was to hand; they took the simple, ordinary things and raised vibrations. They worked magic on the ordinary.

To make something out of nothing is almost godlike in its power. That is why to go beyond function, beyond utility, is the highest in art. It takes us beyond ourselves; it takes us beyond our limited conception of what we are.

Science is limited to our understanding, our measuring and our calculating. Only art can deal with that which we cannot analyse; that which we cannot measure can deal with immeasurability of the heart of man and woman, the unfathomability of our souls. Only art can deal with the deep unease that runs through us, that has no name. It is always communal, even when it appears most individualistic. What one soul truly sees, it truly sees for us all. Art is fundamentally generous.

Maybe the most mysterious thing about art is the way it amplifies our humanity. The truth is that our humanity is like a vast castle that we barely inhabit. There are rooms that are given prominence by education, the moral temper of our times and the secret stories at work in our psyche, but art resonates in those other rooms, those halls and cellars, those unknown spaces, and we shiver in the unknown splendour of our own inner architecture.

Art enlarges our conception of ourselves. It reveals to us our magnificence. It awakens the curious sense of our connectedness. It does it invisibly. It does it in excess of purpose and function and it does it without trying. You could say it’s the electrified space between the sublime mind and the man and woman of the ordinary mind.

In a way, art is a parallel of the creation myth. It is the sign that we are greater than our reality and greater than our history. It is also the magical act of the passing on of power. It is a magical act of the passing on of messages of the sublime. One of those messages, how to decipher and receive by the spirit alone, rarely reaches the conscious mind.

Q You described art as being godlike: the ability to create something out of nothing. Do you think that this arouses fear in those who have power in society?

A One of the most dangerous and troubling things about art is that it always posits an alternative reality, which is very threatening to people who want to hold the world in one frame and manage it. Art is naturally rebellious; if you agree with it today, when you come and look at it tomorrow it will disagree with you.

Abdulnasser Gharem

Former lieutenant colonel in the Saudi army, now an artist

I was in the army for 23 years and it took me around 20 to find a way to combine being a soldier and an artist. The late 90s were the trigger, when the internet came and we started to see artists from America to Africa to China. It inspired me, so I said “Okay, I need to be an artist,” and the art really changed my path.

In Saudi Arabia, the media are controlled by government, so the role of the artist is very important. It’s also hard for the foreign media to get in; this makes the art and the artists important so that the outside world knows about issues through the videos and photos coming out.

Social media are vital because the issues go through them, which forces the official channels to tell the truth because it’s already out there. As an artist you need to be involved in these things.

I did the video called Siraat (the path). You need to find your own path but they want you to follow only theirs. The artist is against the status quo. If you accept the status quo it means you are not making art; I’m sure of that. The artist is against ideology. The artist has the best access to the collective and unconscious mind of the nation. The artist has the privilege that he can open the dark corners in people’s heads.

The artist is pushing people to become individuals. That’s the difference between the artist and people dealing with texts. The artist is giving you space; he’s not directing you; he’s just creating a kind of a spark and waiting for your feedback, and suddenly you’ll come back with your own conclusions that you will promote, which is very important.

In the last five years we have had more than 200,000 kids who’ve been abroad on scholarships and now they come back to the country with a different perspective, so I know something is going to happen; I don’t know what, but as an artist I can feel it.

I have this studio space where talented people can come together and share their ideas and talk freely. I try to fill that [generation] gap until I can get the attention of the government to take care of these kids. I was talking to a member of the royal family two days ago. He knows that I was in the army and he was asking me about it, so I asked him: “Why have you bought all this weaponry?” and he said “For the stability of society, etc etc,” so I said “For stability you need to focus on the youth, because 70% of the population is under 40”.

As an artist you are in the middle where you can see the past, the future and the present. In science, when you have new information it kills the old; you cannot go back to it, but it’s different with art.

Q Do they realise just how subversive you are?

A I think the most important thing for an artist is to be honest, but in the military I also learned that you need to work in the long term.

THE JUDGE

Neil MacGregor

Director, British Museum

What has emerged from this wonderful four-part view of the purpose of art has been extraordinarily coherent, coming from such different positions: from the scientific, the poetic, the religious and military.

John Barrow talked about the fact that what art prepares us to do is understand diversity, to enlarge the human imagination, to prepare us for the unexpected. Karen Armstrong took us straight into the caves at Lascaux. What she insisted on was that art exists in order for us to find new ways of being human, that the awe and the wonder allow us to make a place for the other, because we can enter the mind of

the other.

Poetic journey

Ben Okri led us on that wonderful poetic journey and as we circled and looped he kept bringing us back to the point that the activity of the individual artist allows the whole of society to be changed. His great phrase, “That allows us to discover the splendour of our inner architecture” was, I think, one to cherish. And it is what every one of our witnesses has said: not only are we mysterious and we understand our own mysteriousness but we also become co-creators of the world. In imagining others, we can make and imagine a new world, which, as we heard from Abdulnasser Gharem, is why it is also threatening to an orthodoxy that knows that there is a fixed order that cannot be disturbed, because if it is disturbed, their power will be threatened.

It was a very remarkable journey that Abdulnasser took us on. Very few, having become soldiers, become artists. His great phrase was, “The artist gives us access to the unconscious mind of the nation”. That was really what every one of our witnesses was suggesting; the artist can open, he said, dark corners in the head that nobody else can reach.

I think every one of our witnesses made a really powerful plea for why art matters and, above all, what it is for. It is to enable us to make the world differently and, in that process, to make ourselves differently.

The next investigations

• 15 December: What Is Art For? Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

• 18 February 2016: What Is Art For? Museum of Modern Art, New York

• May 2016: What Is Art For? Vatican

• The events in London and New York are supported by Volkswagen