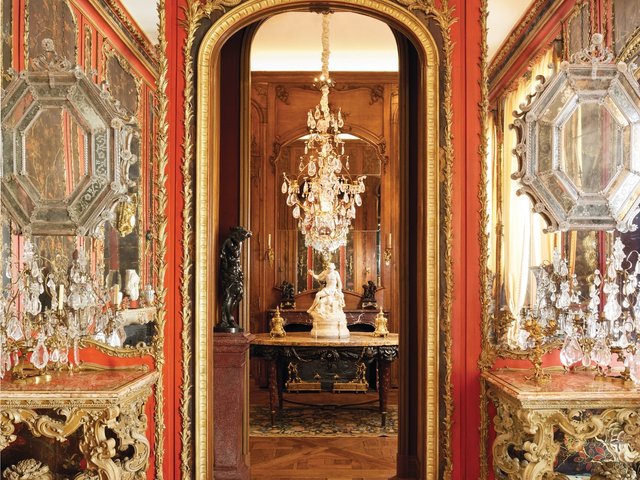

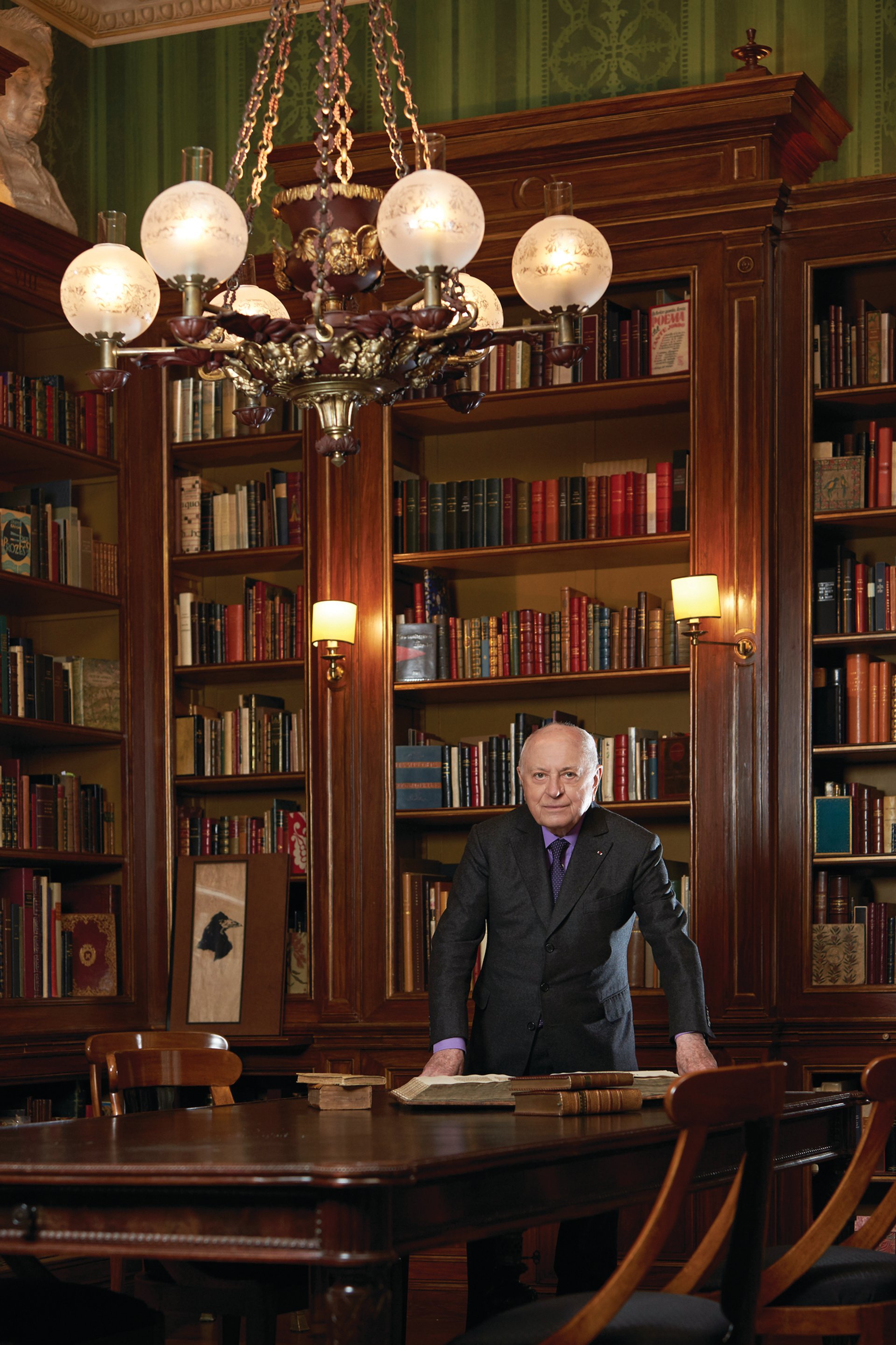

Over more than 40 years, Pierre Bergé has patiently and secretly assembled one of the world’s leading private collections of books. The arts patron, entrepreneur and long-time companion of the late Yves Saint Laurent, with whom he co-founded the YSL fashion house in 1961, has filled his house in Rue Bonaparte, Paris, with 1,600 books, manuscripts and musical scores, dating from the 1400s to the 1900s. This labour of love is also “a kind of autobiography”, Bergé admits.

But that story is now coming to an end. The 85-year-old has decided to embark on a new adventure that means he must part with his personal library, just as he has already begun to auction off his and Saint Laurent’s collection of Islamic objects. “At this stage of my life, my absolute priorities are the two Yves Saint Laurent museums that we are planning to open in autumn 2017,” Bergé says. “One in Paris and one in Marrakech, which I hope to live to inaugurate.”

The library will be sold in several sections (literature, botany, gardening, music, philosophy and politics), beginning this month and running until 2017. The proceeds are destined for the Fondation Pierre Bergé-Yves Saint Laurent in Paris, which will be responsible for the management of the two new museums. The sales will be conducted by Sotheby’s in collaboration with Pierre Bergé & Associés; the first, focusing on literary works, is due to take place on 11 December at the Hôtel Drouot, Paris, with Antoine Godeau as the auctioneer. Godeau was also involved in the 2009 auction of the Saint Laurent-Bergé art collection, which some called the sale of the century: it smashed records and raised a total of around €400m.

“Six sales make sense,” Godeau says, “in order not to invade the market of rare books and to permit people to appreciate and understand the collection better.”

Bergé took the decision to part with his beloved collection after Saint Laurent died from brain cancer in June 2008. “I am 85, I have no heirs and I have to think of the future of the foundation,” he says. “What is important is that I am not selling it because I need money, but because of my belief in the need to ensure the preservation of these books in other hands.”

He pauses, before adding: “I would like to share something important. I always believed that works of art do not belong to one individual. We can own a car or a dog or a house, but works of art belong to mankind. This becomes pivotal in key works from ancient Greece, Italy or Egypt, now in museums all over the world… the best example is the Parthenon sculptures in the British Museum or the works that Napoleon took from his campaigns in Italy or Egypt, many of them in the Louvre. I find it terrific that these treasures are all over and giving the opportunity to people from different countries to enjoy them. In any case, the Greek sculptures could not be [held] at the Parthenon due to reasons such as pollution. The best place for them is the British Museum.”

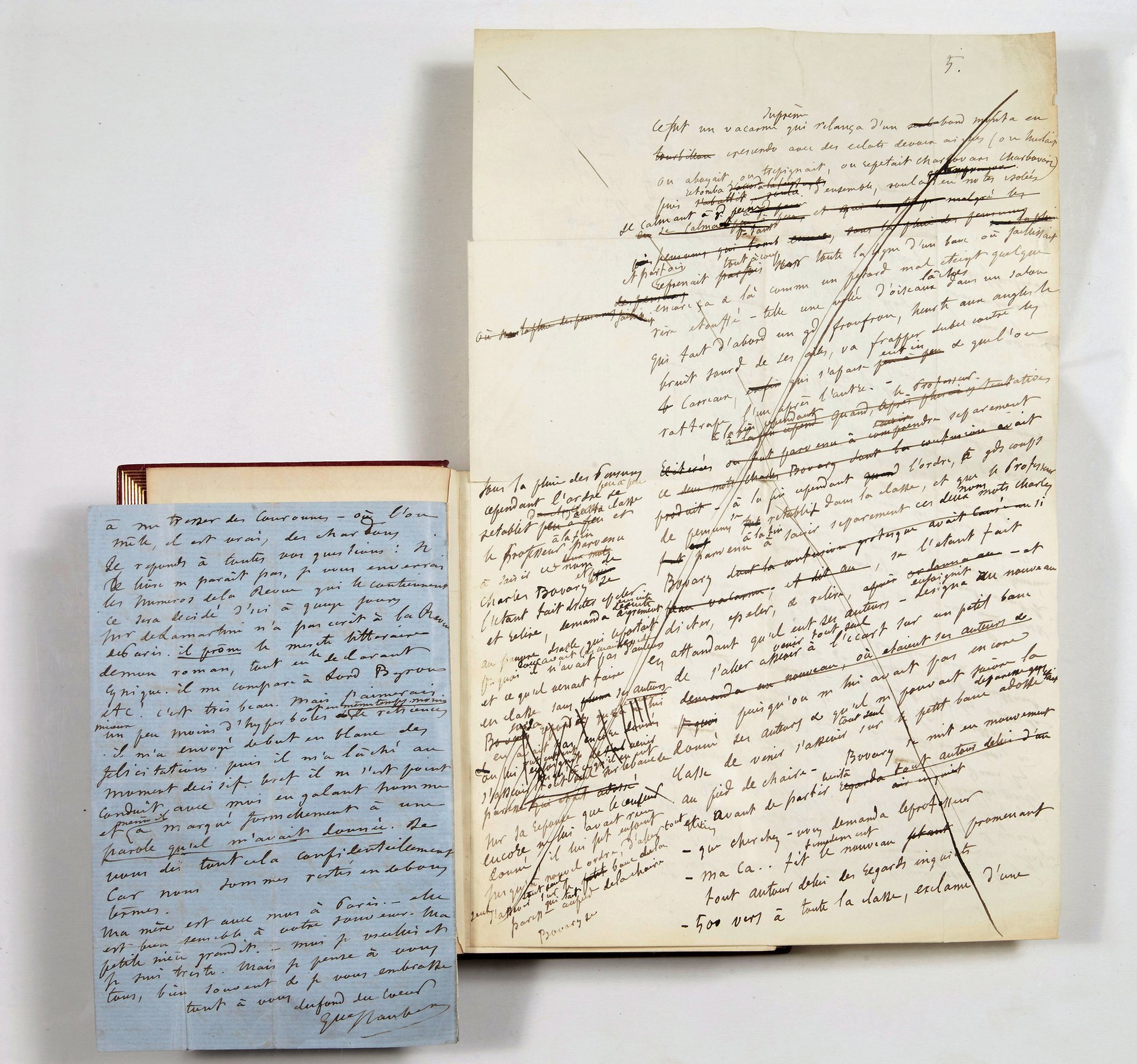

From St Augustine to Burroughs The 150 manuscripts and printed books in the first sale span six centuries, from the first edition of St Augustine’s Confessions, printed in Strasbourg by Johannes Mentelin in around 1470, to William Burroughs’s Scrap Book 3, published in 1979. “It will be a literary anthology,” says Benoît Forgeot, one of the experts working on the sale, “mixing books of great value, such as the original manuscript of Nadja by André Breton or Sentimental Education by Gustave Flaubert [notes and sketches for the novel], and other books of less value but always of excellent quality, of great significance and of enormous interest due to their origin or their annotations.” The Nadja manuscript was acquired by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France ahead of the sale; the Flaubert is estimated at €600,000.

Forgeot adds: “It is a world-class library. There are first editions in all languages. Besides, it is a journey through Bergé’s favourite authors in their original language.” Among the many highlights are Dante’s Divine Comedy, printed in Brescia in 1487; a first edition, published in Florence, of Homer’s works in Greek, from 1488; a third edition of Cervantes’s Don Quixote, published in Lisbon in the same year as the first edition in Madrid; a copy of the very rare third folio of Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories and Tragedies; the first edition of the poems of Michelangelo, published by his grand-nephew in 1623; key French texts including Discourse on the Method by Descartes and Voltaire’s Candide; and a first edition of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island. Forgeot describes the library as “prodigiously abundant and wide-ranging”, with the “most surprising” element being the collection of 19th-century items. “French 19th-century literature is the core of his library, but equally strong is the presence of Russians, including Pushkin, Gogol, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky.”

Of particular significance to Bergé is Charles Dickens’s own copy of David Copperfield. “[This novel] was the first book that really marked Monsieur Bergé at the age of nine, because it was the first adult book he read,” Forgeot says. “From there, he learned the power of words. Each book in his collection is a portal to memories from his past and gives us insight into his involvement in art, fashion and politics.”

Hence Bergé’s analogy to an autobiography. “I come from a world where culture was of the utmost importance,” he says. “I studied music even before I learned to read. I always read books beyond my years.” His first job was as an antiquarian book dealer. “I understood what it was to be a bibliophile at the age of 18 in Paris,” he says, “developing a keen interest in both texts and the quality of the books while looking for treasures in the bookshops on the banks of the River Seine.” His first important purchase, when he was 21, was Gallimard’s complete works of Marcel Proust.

“Books became my friends,” he says. “To have in my hand the first edition of Montaigne’s Essays, one of France’s greatest literary achievements, intact, such as it was printed [in 1580], was one of the most moving experiences of my life.”

In praise of Flaubert

Bergé considers Gustave Flaubert “the best writer who has ever existed; he is pure subject matter”. Some of Flaubert’s works are among the jewels of the collection, such as a first edition of Madame Bovary, published in 1857 (est €600,000). Flaubert gave it to Victor Hugo, with the dedication: “Au Maître, souvenir et homage”. Forgeot describes it as “precious, one of a kind, [a book] that any bibliophile would love to possess”. He adds: “Bergé prefers dedicated books or annotated copies with a story behind them. There is a bit of Flaubert in all the activities of his life, like his alter ego, always in absolute control of style, in the quest for supreme rigour and perfection.”

“I am indeed a perfectionist,” Bergé confirms, “although in real life it becomes complicated.” He will keep only two of the books, both by friends and mentors, and dedicated to him: Jean Cocteau’s Requiem and a volume of Jean Giono’s poems.

“Bergé’s collection is one of the best in the world, but the importance is in its highly personal approach,” says Michel Scognamillo, another of the experts working on the sale. “He would not buy a book because it is a ‘must’, because it will complete a period or because it is by a certain author. This explains absences, such as Albert Camus.”

Forgeot adds that the library “is the mirror of Bergé: pure French but open worldwide, extremely rigorous but very sensitive, a man loyal to his friends but a lover of risks and adventures, and above all, a surprising man, far from any political correctness”. The more unexpected aspects of Bergé’s personality are reflected in the two most recent lots: the writer Yukio Mishima and the photographer Eikoh Hosoe’s collaboration Barakei (Killed by Roses), from 1963, and William S. Burroughs’s artist’s notebook, Scrap Book 3, published in 1979.

The first sale will contribute an estimated €8m towards the two new museums. “Yves and I often discussed the idea of creating a museum,” Bergé says. “Early in the 1970s, Yves had the intuition—when no couture house took care of conservation—to keep outfits of value as artistic heritage.” The Fondation Pierre Bergé-Yves Saint Laurent owns 5,000 haute couture outfits, 1,000 YSL Rive Gauche (ready-to-wear) outfits, 15,000 accessories and 100,000 to 150,000 of Saint Laurent’s drawings, plus numerous photos and documents. This archive is the core content of the new museums.

Florence Müller, a fashion historian and former director-curator of the Union Française des Arts du Costume, says: “To understand how this process is exceptional, one has to imagine that there is no other example of a museum devoted to one couturier with such a large archive. The richest collections, such as Chanel, Lanvin or Dior, would have, as a maximum, a few hundred pieces.”

The focus of Bergé’s plans for the museums has shifted over time. “At the beginning, we dreamed of a museum blending our art collection with the finest examples of Saint Laurent fashion designs,” he says. The project turned out to be too complicated and too expensive. “We had no back-up from the French authorities,” Bergé admits, regretfully. “It was quite frustrating. Maybe if we had been Qatari, things would have been different.” Nevertheless, as he puts it: “I have the money and I’ve decided that I can do it myself. Ultimately, there is a great advantage to creating the museums independently, as we will do it as we please.”

But why museums in both Paris and Marrakech? “Two museums makes complete sense,” he says. “It is natural that a museum [dedicated to] Yves Saint Laurent exists at Avenue Marceau, where he worked his whole life, and that the other is in Marrakech, because it was the city in which Yves chose to live. When we discovered Marrakech in 1966, he immediately decided to buy a house there and go regularly. So it is perfectly natural to build a museum devoted to his work, 50 years later, in a country to which he owed so much.”

Oasis in Marrakech

Morocco would become Saint Laurent’s inspiration throughout his career. In 1980, he and Bergé acquired the Bauhaus-inspired Villa Oasis in Marrakech, together with its neighbouring botanic garden, the Jardin Majorelle, which was created in the 1930s by the French painter Jacques Majorelle. They restored both the house and the garden. There, Saint Laurent, who was born in Oran (Algeria), rediscovered the sense of colour that he would use in such a revolutionary way in his couture collections.

“After each show in Paris, Yves Saint Laurent returned to rest here,” remembers Quito Fierro, the secretary-general of the Jardin Majorelle complex, which now houses the Berber Museum amid its colourful gardens. “All his collections were sketched and created here, in the gardens. He would do all his imaginary trips to Russia, India, China or Japan here.”

The recent sale of Bergé and Saint Laurent’s Islamic art collection, in the salons of the Palace Es Saadi in Marrakech, set a record in the field: it made a total of €1.4m, which will go towards the museum in the city. Bergé says that he and his partner were gripped by Islamic art from their first visit to Morocco in 1961, and throughout their years in Marrakech. “We loved Arab artisans, and Yves enjoyed walking in the souk and [Marrakech’s] Jemaa el Fna square,” he says.

The new museum will be metres away from the Jardin Majorelle, in the same street, which is called Rue Yves Saint Laurent. “The opportunity arose two years ago, when a 2,650 sq. m [plot of] land was up for sale,” Quito Fierro says. Construction began in September, with Studio KO, the practice of Karl Fournier and Olivier Marty, as architects. The firm, which has offices in Paris and Marrakech (and has collaborated with Bergé before), is planning a 3,200 sq. m museum with Moroccan twists, in keeping with the luminous hues of the Jardin Majorelle. It will display a rotating selection of around 200 haute couture pieces.

Bergé says that the museum will be “a pioneering art centre in the country”, with a 120-seat auditorium, a restaurant, a coffee shop and a library with 5,000 books, “on YSL and fashion, botany, the Arab-Andalusian culture and Berbers”. The director will be Björn Dahlström, who is currently the director of the Berber Museum in the Jardin Majorelle. No director has yet been appointed for the museum in Paris. This institution will occupy the foundation’s present home, which will be completely refurbished after its current exhibition, on Jacques Doucet and Saint Laurent (until 14 February).

“The Paris museum will include the mythical studio of Yves Saint Laurent, which occupies the first floor and will permanently display more than 1,000 haute couture outfits and renovated textiles,” Bergé says.

The two museums will be emblematic of a remarkable relationship: Saint Laurent the visionary and Bergé the energetic figure behind the scenes, who helped his partner to realise the full extent of his creativity. Quoted in Bergé’s book Yves Saint Laurent: a Moroccan Passion is a revelatory tribute written by the designer for Bergé’s birthday in 1984: “Without you, maybe I would not have been who I am/Without me, I do not hope it but I think it, you would not be who you are.”

Bergé is conscious of the truth in these words more than ever. “Indeed, I have devoted a great part of my life to Yves and his legacy,” he says. “The museums will not only preserve his memory—they are in homage to the man and his genius, which had no end.”

• For more, visit labibliothequedepierreberge.com