Gravity finally came to bear on the art market in New York this month during an unprecedented stretch of seven contemporary, Impressionist and Modern evening auctions held over nine days. Common sense made a comeback as collectors showed increasing awareness of the differences between the great, the average and the just plain ugly.

While there is still plenty of money being poured into the system, as demonstrated by several records and the more than $2.3bn spent on art across the auctions, the number of lots that failed to sell and those that went below estimate suggests that, after years of breakneck growth, the market seems to be reaching a plateau.

“It’s almost like people finally woke up after a 20-year drinking binge,” says Andrew Fabricant, a partner in the Richard Gray gallery. “The market started to [heat up] in 1995 and, with the exception of 2008, this is the first auction season where people seemed to realise that certain levels of rationality should be applied. Prices got pushed to such a ridiculous level that people had to wake up.”

After years of crowing about the stability of art compared with the stock exchange, currency markets or banks, the auction houses are now singing a different tune. Brett Gorvy, the chairman and international head of post-war and contemporary art at Christie’s, attributed the uneven results of its Artist’s Muse sale on 9 November to “turbulence in the stock market”. Meanwhile, Sotheby’s chief executive Tad Smith told analysts during an earnings call last month that buyers were more “sensitive to macroeconomic uncertainties”.

The slowdown may have more to do with the drop-off in the number of new buyers, and the fact that those who remain are maturing in their tastes and outlook. Collectors are increasingly beginning to understand that the sheer volume of work being sold means that they can afford to be more selective. Buyers chased works of importance, rarity or trophy value that were in good condition, but balked at the greed of the auction houses by snubbing average works that had been priced too aggressively.

“The consensus was that the market had become excessive. Now buyers are showing that they don’t want to be taken for a ride,” says Thomas Seydoux, the former international chairman of Christie’s Impressionist and Modern art department who co-founded the private dealership Connery, Pissarro, Seydoux in 2012.

“The market today has topped off and is more serene. People are stepping back a little bit to let it breathe again. It doesn’t mean there is a recession and it’s not a sign of weakness. It’s actually very healthy,” Seydoux says. “The market has given us a soft lesson this season.” Some of the top lots could have easily failed to sell as the competition for them was thin, he adds.

Business strategies changing

Senior managers at Sotheby’s and Christie’s are beginning to refocus their firms’ strategies on the bottom line, rather than on beating the competition, according to sources at both auction houses. In their efforts to attract sellers and gain market share over the last few years, the companies have eroded their profit margins by making generous use of financial sweeteners, such as guarantees or the third-party “partnerships” Christie’s quietly introduced earlier this year. But unprofitable business is simply bad business. Just days after announcing its best ever season of sales this month, in the course of which the firm turned over $1.1bn in art, Sotheby’s launched a voluntary redundancy scheme for staff. The cost-cutting measure could lead to layoffs at the company, which saw its share price plummet to $29.02 last week.

Chinese buyers are in the game

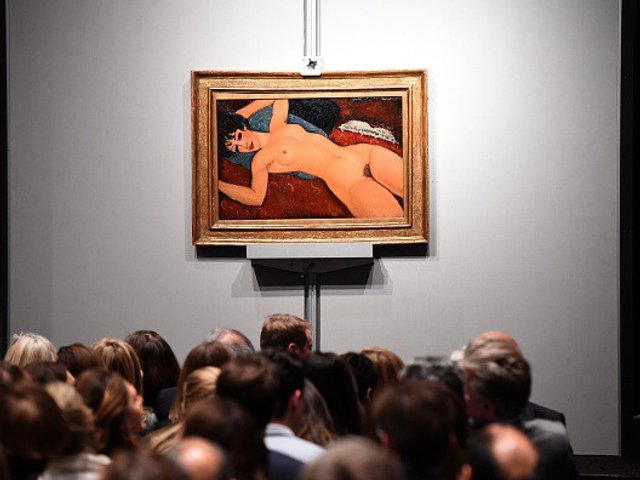

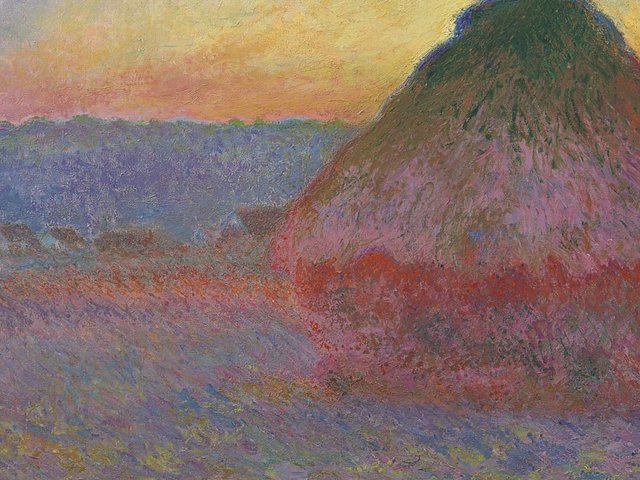

Despite the economic slowdown in China, Asian collectors were responsible for some of the biggest purchases of the auction season. The businessman and former cab driver Liu Yiqian bought Modigliani’s Nu couché (1917-18) for $152m (hammer price) at Christie’s on 9 November ($170.4m with fees; the painting had been guaranteed at around $100m) for his private institution, the Long Museum in Shanghai. Lucio Fontana’s egg-shaped canvas, Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio (1964), which was consigned by the hedge-funder Steven Cohen, broke records when it sold for $25.9m (hammer price) to a Chinese buyer at Christie’s on 10 November ($29.2m with fees; guaranteed at around $25m). During the same sale, an Asian buyer also acquired Calder’s Vertical out of Horizontal (1948) for $8.4m ($9.6m with fees; estimate $2m-$3m). Nonetheless, the pool of Chinese collectors at this level is small—closer to 20 than 200. And they are showing increasing levels of discrimination, ignoring lots by artists such as Monet which they might previously have snapped up.

PLEASE NOTE: Auction houses usually quote the sale price including buyer’s premium while quoting pre-sale estimates without these fees. The Art Newspaper is joining a number of publications in clarifying these by also quoting hammer price so the comparison between the price achieved and the estimate is easily discerned. In London, Sotheby’s buyers’ premium rates are 25% on the first £100,000 ($200,000 in New York); 20% between £100,000 and £1.8m ($200,000 and $3m) and 12% above this. Christie’s and Phillips’s rates are 25% on the first £50,000 ($100,000); 20% between £50,000 and £1m ($100,000 and $2m) and 12% above this.