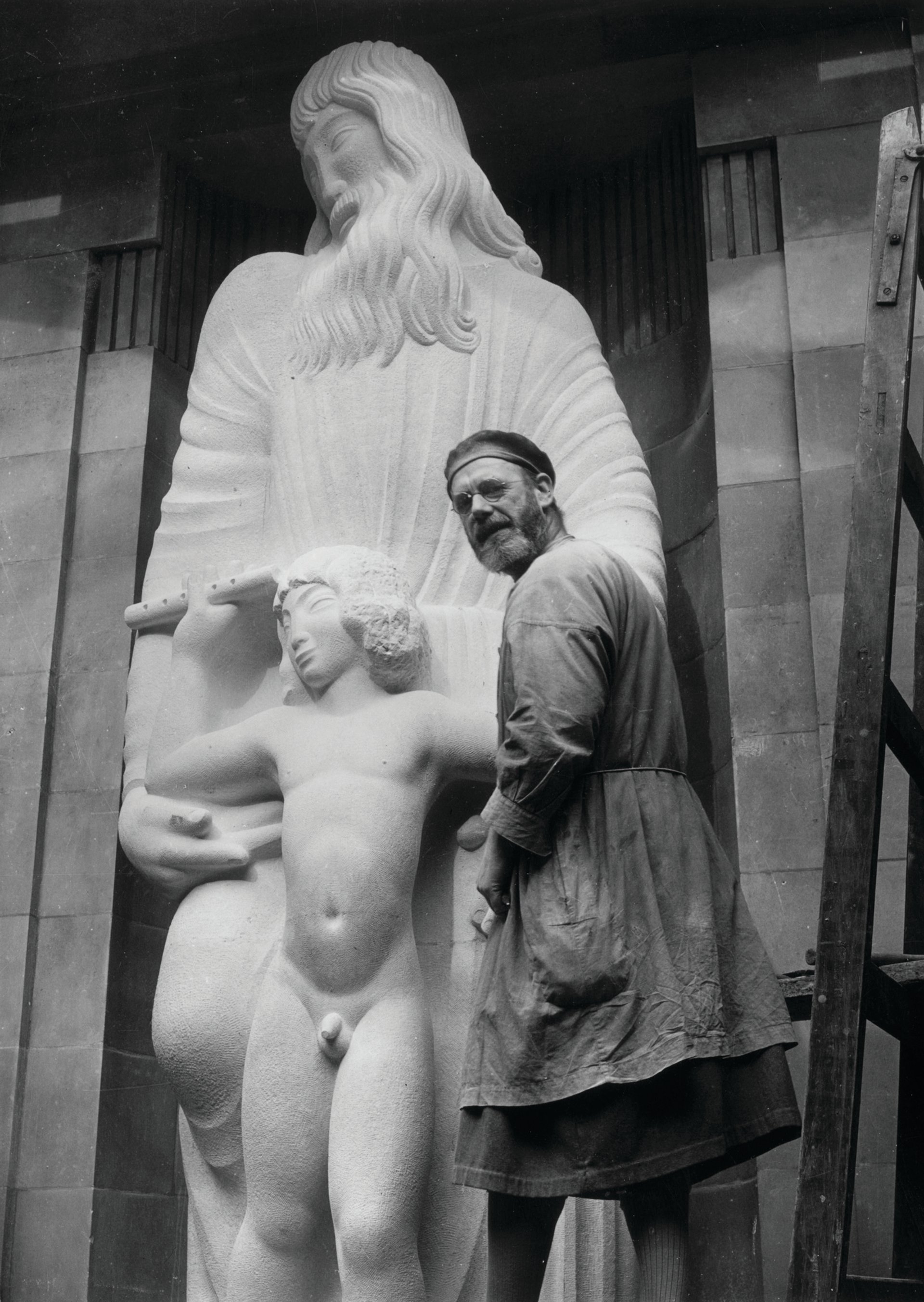

In 1957, Jerry Lee Lewis married his 13-year-old cousin. Is it merely due to the passage of time that, despite this, his music is still celebrated today? Eric Gill abused his daughters and had sexual relationships with his sister and dog. Is it because his work is critically acclaimed that this revelation has done little to dent his reputation as a formidable sculptor? Indeed, his work gilds the BBC’s Broadcasting House.

What is it about the convicted paedophile and celebrated British artist Graham Ovenden that compelled district judge Elizabeth Roscoe last month to order the destruction of his paintings and other works owned by him?

In April 2013, Ovenden was found guilty of six charges of indecency with a child and one charge of indecent assault against a child. The charges related to girls who had modelled for him, and he was jailed for more than two years.

In a magistrate’s forfeiture hearing in London on 13 October, Roscoe assessed for “decency” the contents of the artist’s studio, which included some of his own paintings in addition to his collection of work by other artists. She said she used “recognised standards of propriety that exist today” to come to her decision that several of the artist’s paintings are indeed “indecent” and should be destroyed.

As a matter of law, this is the wrong test to apply, as it covers only photographs and pseudo-photographs under the 1978 Protection of Children Act. When this legislation was passed, no one thought there was a need to cover graphic works such as paintings because they already fell under the Obscene Publications Act of 1959.

The correct legal test for paintings is whether, based on the evidence, people seeing the works in question would be incited to paedophilic or other similar criminal behaviours. Does the material in question have a tendency to “deprave and corrupt” those likely to view it? A quick online search of Ovenden’s work (including the condemned paintings) tells you that the indelible electronic memory of the internet renders the deletion of the originals futile even if the test were satisfied.

One cannot help but think that the judge’s understandably poor view of Ovenden as a man informed her decision to destroy not only his work but pieces by other internationally renowned artists—Pierre Louys and Wilhelm von Pluschow—reported to be in his possession.

There are far more provocative works widely available in the public domain, and, as Ovenden himself has commented, his work has been publicly available for more than 40 years. Judge Roscoe, by her own admission, is no arbiter of artistic merit. She erroneously applied the law and failed to understand why the paintings should survive. She was unlikely to have been assisted by Ovenden’s own submissions as he was representing himself without the benefit of legal advice or art-historical evidence.

A surer-footed legal analysis would have placed the works in their proper art-historical context and considered other relevant factors and questions that were ignored by the judge in her flawed decision: the fact that Ovenden was a founding member of the Brotherhood of Ruralists; who had seen the paintings and who would be likely to see them in the future and in what circumstances? And would the destruction of the original works (as opposed to images online) in itself prevent the depraving and corrupting of others likely to view the images?

Art tells a story; it denotes its time and place and is therefore utterly irreplaceable. Is it ever acceptable to delete history? At a time when cultural property pertaining to national identity is under threat in many parts of the world, is it acceptable to delete part of ours, irrespective of how heinous the artist’s personal behaviour may have been?

Prodigious and diverse artistic talent is often married to personal disturbance, yet possessors of such talent continue to have their work widely celebrated, despite public knowledge of their personal wrong-doings, delinquencies and crimes. In addition to Lewis and Gill, the works of the film-maker Roman Polanski, the authors J.M. Barrie and Lewis Carroll and the composer Benjamin Britten, to name but a few, fail to be marred by rumours about their behaviour.

Others, such as the musician Ian Watkins and the artist Rolf Harris—both found guilty of, and jailed for, sexual offences against children—have rightly been hung, drawn and quartered by the court of public opinion. It is no longer socially acceptable to celebrate their work, irrespective of its quality, but even so, it has not been destroyed.

This poses the question of the suitability of a judge hindered by visual illiteracy to properly decide what is indecent to the public. Art lovers and members of the public alike should have the liberty to decide what they wish to view and what they do not. Public perception is likely to evolve with time, as it has with Gill. Rolf Harris’s portrait of the Queen has not been destroyed, despite the fact that he is serving a near-six-year prison sentence for 12 indecent assaults. It has simply been removed from public view. This is in keeping with the approach taken by the British Library and other libraries of record, which store under lock and key illustrated volumes considered to be obscene because these institutions recognise the public interest in the survival of such works.

Judge Roscoe’s decision also risks flouting Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights, which protects valid exercises of artistic freedom. Any restriction must be strictly necessary in a democratic society in order to protect against crime or injury to morality. Can it really be said that Ovenden’s work incites others to paedophilia?

Ovenden’s art has not changed. It is the same art that graced the Piccadilly and Leicester galleries. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the McCrory Foundation in New York have both shown his work, and it has also been seen on the BBC, on ITV and on Channel 4. In short, his work has received international recognition and dissemination. Famously, Princess Diana even commissioned a piece depicting a child’s bare bottom. The only difference is that now the artist is a known paedophile.

What about the victims? The law is set up to protect those who could be harmed by Ovenden’s work—namely, the subjects of it. If any of the models in the pictures object to the works being publicly available, then, without question, they should not be. However, destroying the paintings not only destroys part of an artistic canon: it deletes the evidence that abuse took place. Survivors need witnesses; the telling of an experience is a crucial part of the healing process. But when the works are gone, the victims will be permanently deprived of them.

Museums in possession of Ovenden’s work should preserve it for the survivors and until such a time that the public wants to review it. When it comes to displaying the works publicly in the future, they should rely on a defence provided for in the Protection of Children Act—that there is a “legitimate reason”.

The importance of Ovenden’s work and his position within the cultural history of British art provide ample reason for possession and display of his paintings. His personal behaviour should not infect how his art is viewed. Perhaps it is not possible to divorce the art from the artist, as Judge Roscoe has demonstrated in her decisions, but this makes the works more culturally significant. Crucially, the works tell a story and should not be erased as if they never existed, because it is through history that we learn.

•The author is the head of art and cultural property at London-based law firm Howard Kennedy