For decades, they were simply known as “the Bechers”: it was difficult, indeed impossible, to imagine one without the other. From 1976, when Bernd Becher became the first professor of photography at the Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf, Hilla Becher worked with him on equal terms, training young art students in photography. The teaching took place, conveniently, in the Bechers’ home.

The history of 20th-century art includes a number of significant couples who lived and worked together—Sonia and Robert Delaunay spring to mind, as do Sophie Taeuber and Hans Arp. Yet in all these cases, both partners retained an individual style. With the Bechers, it was different. If ever there was a body of work so deeply indebted to a combined creative effort that the artists can be referred to only in the plural, it is that of the Bechers.

Two hearts, one body of work The death of Hilla Becher on 10 October at the age of 81—she survived her husband by eight years—finally brought down the curtain on this oeuvre. Overall, the Bechers’ body of work is one that did have beginnings, but it then moved straight on to its mature phase, where it stayed. Their work did not reach a conclusion, and could probably never have done so. “There is still so much to do,” lamented Hilla Becher when I was permitted to speak to the couple about their work in 2005. “Permitted” is the right word here—although the pair did not distance themselves from the world, they did prefer to let their work speak for itself.

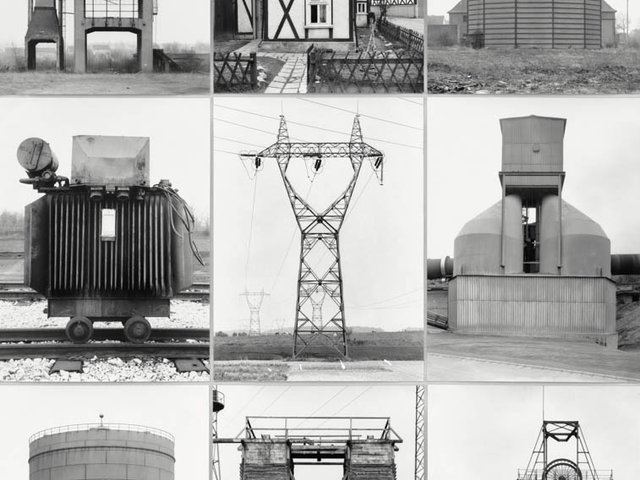

To describe this work as impersonal is not to underplay the photographers’ enormous dedication to their work. Excluding all personal style was, after all, their mission: they wanted to let the objects to which they devoted their tireless attention—and an understated affection—speak for themselves. The objects of their passion were the machine installations of the Industrial Age; the epoch’s name describes its primary characteristic, although the time period it covers varies significantly from place to place. I am in Tokyo as I write this, a city as post-industrial as any in the world, and yet one of its many private museums is currently staging an exhibition that includes works by the Bechers.

It is still—still!—the case that an exhibition of these photographs (accompanied as usual only by succinct location details), whether presented as individual large-scale images or arranged in rows and tableaux in the “typologies” so favoured by the Bechers, is understood by the public. And that is a public, it should be noted, that increasingly rarely has any personal visual memory of the industrial structures depicted. It is no exaggeration to say that even today the Bechers’ work, however much or little precise knowledge the individual viewer may bring to it, both preserves and defines the image of an entire epoch. Is it possible even to imagine a blast furnace, a winding-gear tower or a gas holder any other way than as the Bechers saw it—that is, without any distortion or dramatisation, set against a blank and cloudless light-grey sky?

Focusing on the object However difficult it might be—inappropriate, even, in this particular case—to separate the partners’ individual contributions to their shared work, we can nonetheless assume that Hilla’s distinctive input was to have embedded this impersonal, objectifying impulse in the pair’s vision. Bernd initially used drawing to capture industrial monuments (fast disappearing even then) during his artistic training in the 1950s. Hilla, however, had undergone rigorous training as a photographer, and in a context where the object alone held pre-eminence over any personal style—an anti-artistic position from the perspective of 1950s West German photography, where the concept of “subjective photography” held sway.

Born Hilla Wobeser in Potsdam, in the east of Germany, on 2 September 1934, she trained in the studio of a renowned photographer—one whose father had had the title of “court photographer” conferred on him. In the GDR (as East Germany was commonly referred to) after the Second World War, there were only ruins to document in Potsdam; the former Prussian royal residence had been reduced to rubble and ashes in April 1945. In the GDR era, reconstruction was confined almost exclusively to the sumptuous Sanssouci palace.

Hilla, though, learned to use photography as a documentary medium. After moving to Hamburg in West Germany in 1954, she worked for an aerial photography agency: not a place to develop a distinctive personal style. From 1957, she worked for an advertising agency in Düsseldorf, where she met Bernd, whom she married in 1961. A shared enthusiasm for industrial structures and large-scale industrial technology led the Bechers to begin recording industrial archaeology, initially as a hobby. It was not until the mid-1970s that a commission to document the Art Nouveau-style Zollern II colliery in Dortmund paved the way for a professional career in industrial photography. The research project they published as a book in 1977 focused on the colliery architecture—it contained not a single mention of the Bechers’ photography as a form of artistic expression.

After Bernd’s sudden death in June 2007, Hilla continued the project of indexing and cataloguing their extensive body of work on her own. She continued the photographic work, too, although she concentrated mainly on filling in specific gaps in their coverage.

She died in Düsseldorf, having suffered a stroke shortly before. The previous year she had accepted a special, if late, prize, recognising her own artistic achievement. It is thanks to the Bechers that documentary photography is now seen as an art form in its own right.

• Hilla Becher, born 2 September 1934, died 10 October 2015