It is an oft-repeated observation that drawings present the innermost workings of the artist’s will to form. With the Florentine High Renaissance master Andrea del Sarto’s art, however, much more is at play: drawings played a multitude of roles in the evolution of his paintings. For one thing, as his former pupil Giorgio Vasari observed, they “served him rather as memoranda of what he had seen than as models from which to make exact copies in his pictures.” As Julian Brooks explains in the excellent accompanying catalogue for the exhibition Andrea del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action, now on view at the Frick Collection in New York, the artist would rethink a painted figure and then execute a relatively finished drawing as an aid to the soon-to-be-revised picture. He also made use of partial cartoons as he worked out his designs, or did variations of previous ones. Infrared reflectography, allowing one to detect the artist’s underdrawing beneath the paint surface of a picture, added important insights into Andrea’s art as long ago as 1986—an annus mirabilis for the artist, who was the subject of a momentous exhibition at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence.

Today, only around 180 of his drawings are known, of which about half are preserved in the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe at the Uffizi in Florence. Eighteen of those were generously lent to the Frick exhibition. The second biggest repository is at the Louvre, which hosted a somewhat larger exhibit of his graphic work in 1986 on the 500th anniversary of his birth. The museum has lent three works to the Frick. (Other lenders include the British Museum, London, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, and the Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.)

All totaled, 45 drawings are presented at the Frick, along with three paintings by Andrea that are stunningly displayed in the museum’s Oval Room: Portrait of a Young Man (around 1517-18), in which the soft coloring and limpid paint handling seem the work of some incomparable pastellist; Saint John the Baptist (around 1523), a tour de force of naturalism and sensuality; and the Medici Holy Family (1529), with an accompanying display panel outlining that composition’s under-drawing and cartoon transfer lines.

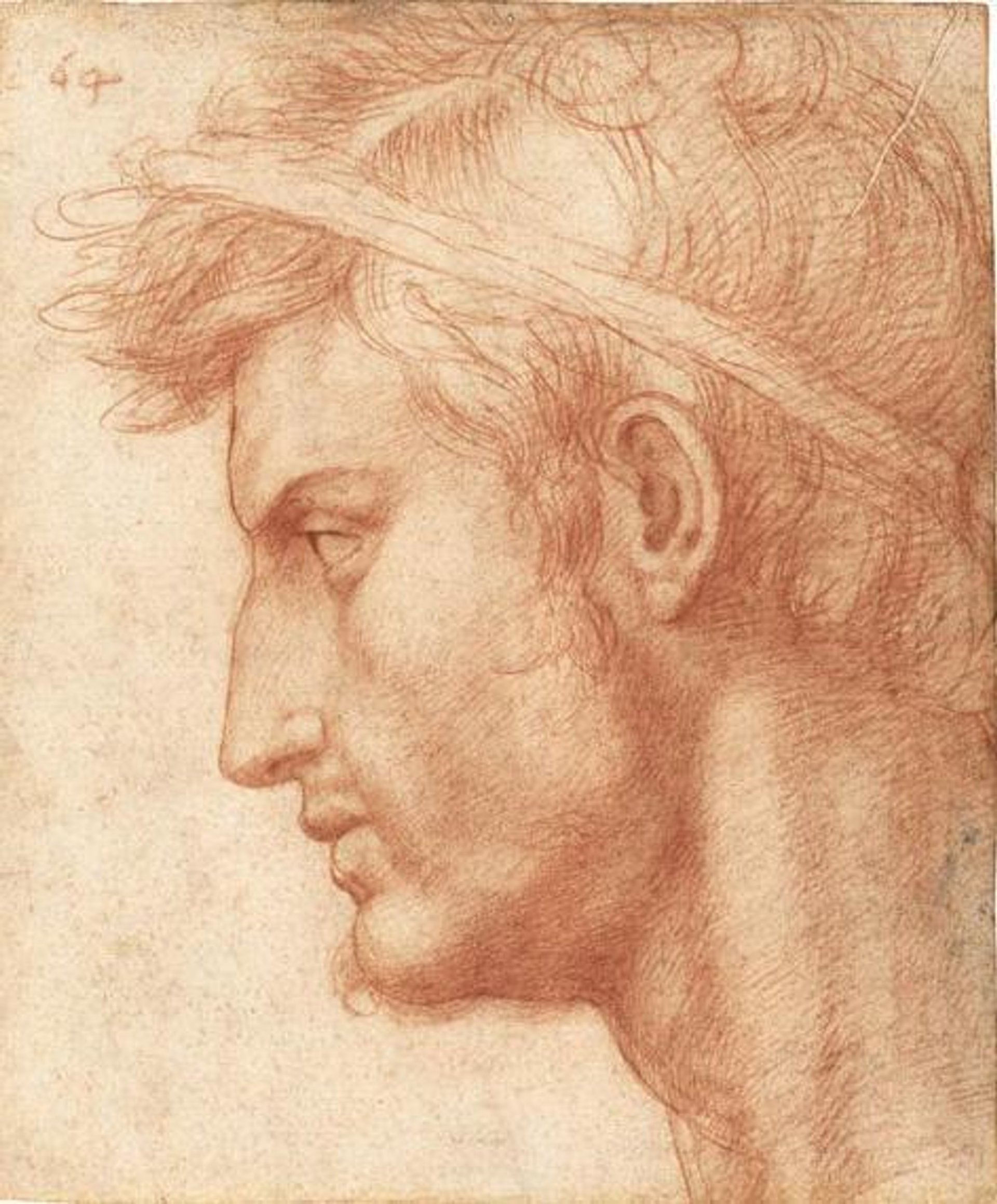

At the start of the exhibition is the beautifully modeled, red chalk Head of Julius Caesar (around 1520), a salesroom discovery that is also a preparatory drawing for the key figure in Andrea’s scintillating fresco at the Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano. The work announces a string of marvelous head studies on the far wall of the room, a drawing type for which the artist enjoyed lasting renown. These are remarkable for their immediacy and their nuanced sense of character. Viewing the black chalk Head of a Young Woman (around 1517) from the Frits Lugt Collection, one wonders: is this the legendary Lucrezia del Fede, Andrea’s wife, who, according to Vasari, wreaked havoc on his career? How beautifully and tenderly Andrea renders the turn of the woman’s head, as it emerges from shadow, adding a sense of mystery to his subject, in a manner recalling Leonardo. A great work, also, is the red chalk study for the Magdalen figure in the San Piero in Luco Pietà (around 1524) from the Palazzo Pitti, a painting that Bernard Berenson went out of his way to decry. In this drawing, more so than in the painting, the saint appears thunderstruck by the pathos of Christ’s death.

In the other room downstairs at the Frick is a selection of Andrea’s rare compositional drawings. A Madonna and Child with Four Saints from the Louvre (around 1509) has the look of a modello done in the style of his sometime teacher Piero di Cosimo and that of Andrea’s own, earliest frescoes at the Chiostro dello Scalzo in Florence. This makes an interesting comparison with a later red chalk sketch (around 1528), which is preparatory for the artist’s Sarzana altarpiece, formerly in Berlin, which was destroyed in the Second World War. Both of those works present Andrea at his most inspired. In the drawing, one senses the artist rapidly laying out the essentials of the scene, a sacra conversazione in which all of the saints’ poses and traits are brilliantly delineated. Equally striking is the effect he creates of an outdoor setting. Near to this are six studies for one of Andrea’s masterpieces, the Madonna of the Steps (1522) in the Prado. Among them is surely one of the most beguiling images of an infant in Italian Renaissance art, the red chalk head of the Christ Child lent by the Uffizi.

Further exploration of Andrea’s working methods is provided by an excellent, small, focused exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which brings together two of his works: the museum’s recently-conserved Holy Family (1528 or 1529), which is one of the finest High Renaissance pictures in America, and Charity (before 1530) from the Samuel H. Kress Collection at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. The latter, it turns out, began as a version of the New York Holy Family, reduced in size by one tenth. Related drawings from the Louvre and the Uffizi are illustrated on wall panels (although no mention is made of a study for the head of the Baptist featured in the exhibition at the Frick). Also on display is a very fine version (lent by Mrs. A. Alfred Taubman) of Andrea’s Madonna and Child at the Palazzo Pitti, Florence. The wall texts describing the technological examination of the two works, by Michael Gallagher, Conservator in Charge of the Department of Paintings Conservation, are models of clarity and concision. So are the texts by Andrea Bayer, Jayne Wrightsman Curator of European painting at the Metropolitan, that recount the exceptionally rich historical context of the Charity and Holy Family paintings. In the latter work, especially, the painter attained one of his highest achievements senza errori—without error. In recognition of this, perhaps, he depicted himself in the guise of Saint Joseph, gazing intently at the viewer. That this figure is indeed the painter seems corroborated by the identical face in the Uffizi drawing illustrated on the gallery label nearby, an image of even starker intensity and self-scrutiny.

Eliot Rowlands is a New York-based freelance art historian who specializes in early Italian paintings. Among his publications are The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Italian Paintings, 1300-1800 (1996) and Masaccio Saint Andrew and the Pisa Altarpiece (2003).

Andrea del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action, Frick Collection, New York, until 10 January 2016

Andrea del Sarto’s Borgherini Holy Family, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until 10 January 2016

Correction: An earlier version of this article misidentified the author of the technical wall texts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They were written by Michael Gallagher, not Andrea Bayer.