There is an art-historical revolution afoot. Curators and critics across the globe are rewriting the story of Pop art, long associated with Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist and Richard Hamilton. Over the past two years, a host of exhibitions and publications have shown that Pop was not exclusively a British and American phenomenon. Artists, including many long-overlooked female practitioners, in São Paulo, Prague, Tokyo and Düsseldorf were equally fascinated by advertising and consumer culture and used that imagery to create incisive, often political work.

Art dealers at Frieze are hoping that the renewed scholarly interest in Pop will inspire collectors to take a closer look. More than a dozen artists from recent Pop exhibitions have a significant presence at the fair this week, including Wanda Pimentel, from Brazil, and Maria Pinińska-Bereś, from Poland. Meanwhile, the work of the Japanese artist Keiichi Tanaami from the 1960s and 1970s is also being rediscovered.

“We had accepted a given history of Pop that was written the moment it arrived,” says Jessica Morgan, the director of the Dia Art Foundation in New York, who co-organised The World Goes Pop at Tate Modern (until 24 January). Because of language barriers and Eurocentric attitudes, “we didn’t bother to look into what was happening in other places”. Some of the artists in the Tate’s exhibition “have not shown since the 1960s, when they first produced the work”, she says.

The reappraisal of Pop is part of a larger shift among art historians, who are re-examining art from the 1960s and 1970s with fresh eyes. Many are drawing parallels between movements—such as Japanese and American abstraction or South American and Italian conceptual art—that had previously been unexplored. “It’s a tendency right now to take a second, third or fourth look at a time we assume we understand,” Morgan says.

Scholars of the past avoided Pop. “People thought it was so accessible that there wasn’t anything to delve into,” says the critic Thomas Crow. His book The Long March of Pop: Art, Music and Design, 1930-95, published this year, puts the movement in a broader context, linking it to American folk art and the Los Angeles punk scene.

Now, curators are realising that there is more to the Pop story. In the 1950s and 1960s, artists worldwide responded to the glut of images in magazines, on billboards and on television with common techniques. They embraced figuration, newly available materials such as plastics and “the reduced language of image-making, like silhouetting and flattening”, Morgan says.

Some artists included in today’s Pop shows dislike the term. Darsie Alexander, the director of the Katonah Museum of Art in New York, says that many artists had to be convinced to take part in International Pop, the touring exhibition she co-organised as chief curator of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (now at the Dallas Museum of Art, until 17 January). “They thought of it as an American phenomenon,” she says. The Croatian artist Sanja Iveković says in the Tate’s catalogue: “Pop art seemed to be an almost exclusively male movement, so it wasn’t inspiring for me.” (Around 40% of the artists in the Tate’s show are female.)

Other recent exhibitions include German Pop at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, which explored work by West German artists including Peter Roehr and Manfred Kuttner, and Post Pop: East Meets West at the Saatchi Gallery, which examined Pop’s impact on artists in the former Soviet Union, China, Taiwan, the UK and the US. “It wasn’t a global phenomenon—it was country by country and city by city,” Alexander says. More than a style, “Pop was a spirit, a fascination with consumer culture and mass distribution systems”.

Dealers hope that the label will add sheen to previously overlooked artists, particularly as high-quality work by marquee Pop names becomes harder to find. Prices for works by, for example, Martial Raysse, Mario Schifano and Gerald Laing have climbed steadily at auction, but only Raysse has passed the £1m mark. By comparison, Warhol’s Silver Car Crash (1963) sold for $105.4m at Sotheby’s in 2013. Beyond key American figures, Pop “has been under the radar”, says the art adviser Kristy Bryce. “But it won’t be for much longer.”

Frieze goes Pop

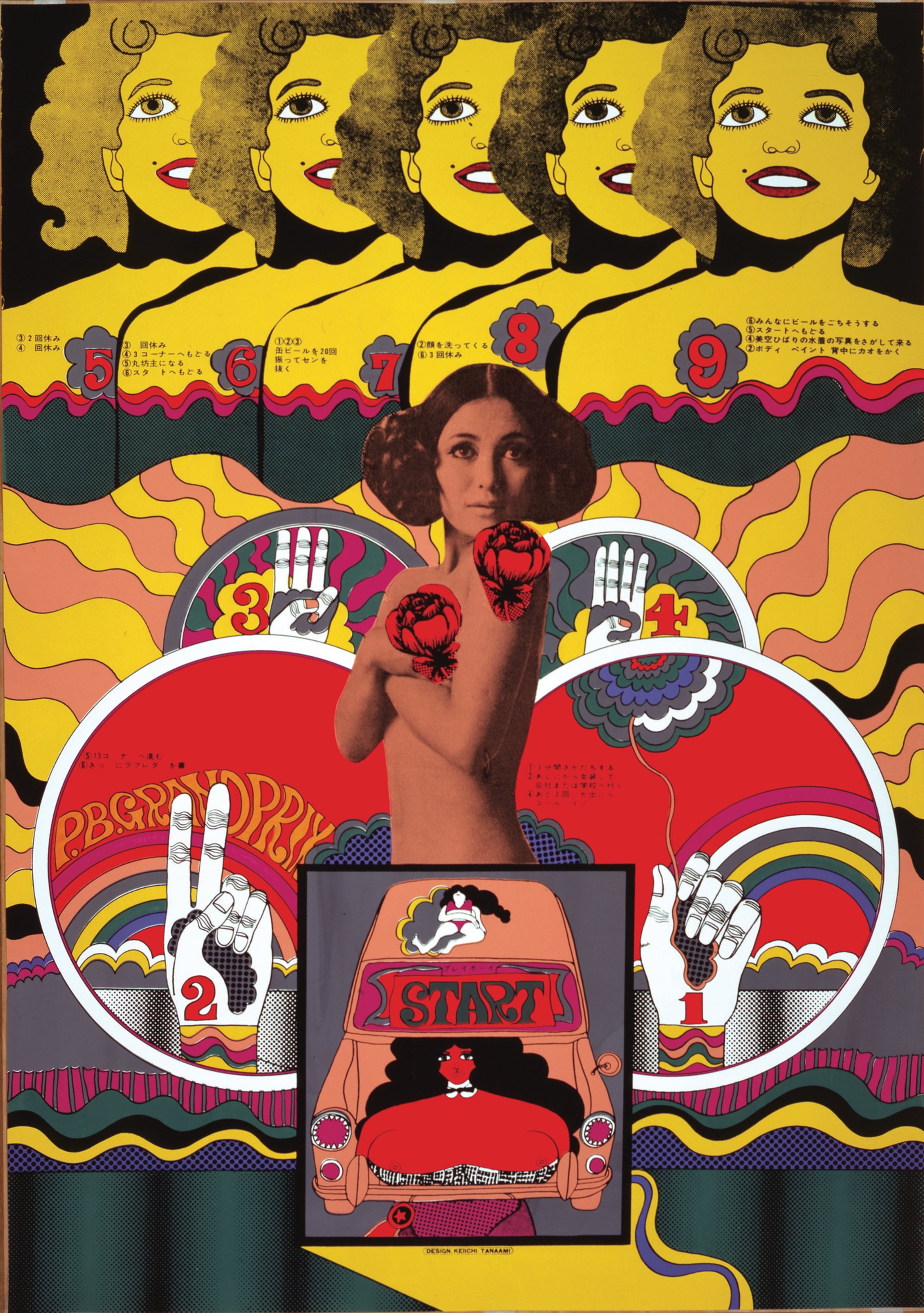

Keiichi Tanaami

A prominent graphic designer in his 20s, Keiichi Tanaami was the first art director for the Japanese edition of Playboy. He felt ambivalent towards the US, which was responsible for the air raids that terrorised him as a child during the Second World War, as well as the Disney films and comic books he loved. Nanzuka Gallery (FM, H8) presents works by Tanaami from the 1970s, including collage, paintings, animations and this silkscreen work, P.B Grand Prix_2 (1968). Until recently, Tanaami’s collages had not been shown publicly. “No critics or galleries showed interest in these works, so he just tucked them away in storage, only to rediscover them in 2012 or 2013. I find this pretty scandalous,” the art historian Hiroki Ikegami writes in the International Pop catalogue. Tanaami’s works at Frieze Masters range in price from $3,500 to $35,000.

Wanda Pimentel

The Brazilian artist made graphic design-inspired portraits of women at a time when most of the country was focused on the military regime and uninterested in conversations about gender. “Everything in her work—themes, images, colouring, space connection and graphic structure—is used to increase a feeling of oppression and confinement,” wrote the critic Frederico Morais. Anita Schwartz Gallery (FM, H14) presents six works from Pimentel’s Involvement Series (1968-75), including this piece from 1969; the series also featured in International Pop. “Until a few years ago, the value and the importance of the 1960s works was, sadly, underestimated,” Anita Schwartz says. The works at Frieze are priced between £45,000 and £60,000.

Maria Pinińska-Bereś

When Dawid Radziszewski (FL, H35) organised a show of drawings by Maria Pinińska-Bereś at his Warsaw gallery in 2013, the Krakow-born artist was barely known. “I was aware that this exhibition would probably be attractive to 15 Polish art historians,” Radziszewski says. The World Goes Pop at Tate Modern includes uncanny installations by Pinińska-Bereś (1931-99), who placed pillow-like forms, evoking women’s body parts, inside display cases. At Frieze, Radziszewski is presenting work from the 1970s, including Circle, 1976. “It is a little less ‘Pop’, but rather connects with the artist’s interest in land art and happenings,” he says.