“The history of fashion tells the history of France,” states Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell in her welcome book about dress at the court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. This comment, like that supposedly made by Louis XIV that fashion is the mirror of history, could be made in general terms about all countries at all times, but the author makes a convincing case that this was particularly true with regard to the reign of Louis XVI. This in many ways created the scene for the intense relationship between politics and clothing that occurred during the French Revolution among all classes of society. Chrisman-Campbell’s concern, however, is not le peuple, let alone the bourgeoisie, but the elite at court who, especially during the 1780s, flirted with the various degrees of radical thought. They adopted, in a decade of Anglomania, simple styles of fashion in non-luxurious fabrics that acted as the Trojan horse of “democracy”.

Wolves in costly clothing

But fashion, apparently so frivolous and carefree, was to prove a dangerous pastime, which explains the title of this book, Fashion Victims. Fashion was a sine qua non of a stylish court dominated by women, but when carried to extremes, resulted in them being labelled as enemies of the people because of their clothing. There is a yawning abyss between the vast, hooped, excessively decorated and costly court dress, the grand habit (established by Louis XIV) that we see in Vigée Lebrun’s portraits of Marie-Antoinette (ironically, a costume she disliked), and the stark simplicity of the loose morning dress depicted in Jacques-Louis David’s famous and horrifying sketch of the former queen, her hair cut short for the guillotine. We read the various narratives of fashion through images of Marie-Antoinette and the ladies of her court, and through a wide range of contemporary accounts, knowing, with the virtue of hindsight, how the story will end.

Chrisman-Campbell’s book is divided into four parts, in a roughly chronological survey, from the accession of Louis XVI in 1774 to the end of the monarchy in 1792, the consequent demise of fashion in France, exiled abroad, and its gradual recovery after the downfall of Robespierre in 1794. Interspersed are detailed discussions of themes such as court dress and mourning, and the various influences on fashion, like the theatre and Orientalism. A few of these sections are somewhat slight; those on the petite-maîtresse (fashion victim) and on marriage. Others are perhaps too protracted, and not altogether convincing, such as the discussion of fashions à l’Américaine. Surely those extraordinary headdresses with ships in full sail celebrating French naval victories over the British in the War of Independence were “rhetorical conceits” and not real? But most of the essays are illuminating, even when much of the material is not new. Chrisman-Campbell is especially good in her discussion of the marchandes de modes, especially the queen’s favourite, Rose Bertin, whose imagination and creativity, often incorporating topical political references, helped to turn fashion into a form of art. More, I think, could be made of the way in which Marie-Antoinette was the “creation” not just of herself but also of Bertin and Vigée-Lebrun; fashion increasingly was about image, about the culture of appearances.

During the second half of the 18th century, a number of writers celebrated French fashion as a unifying and civilising force in society. As Daniel Roche has noted, it became “one of the major themes of Enlightenment thinking”; as technology enabled the production of cheaper and attractive fabrics, fashion also became a vehicle of popular expression, available to an increasing number of people. The manufacture of fashionable clothing and accessories in any country was big business; in France it was a crucial engine of the economy. Fashion was aspirational, cultural and political: it mattered.

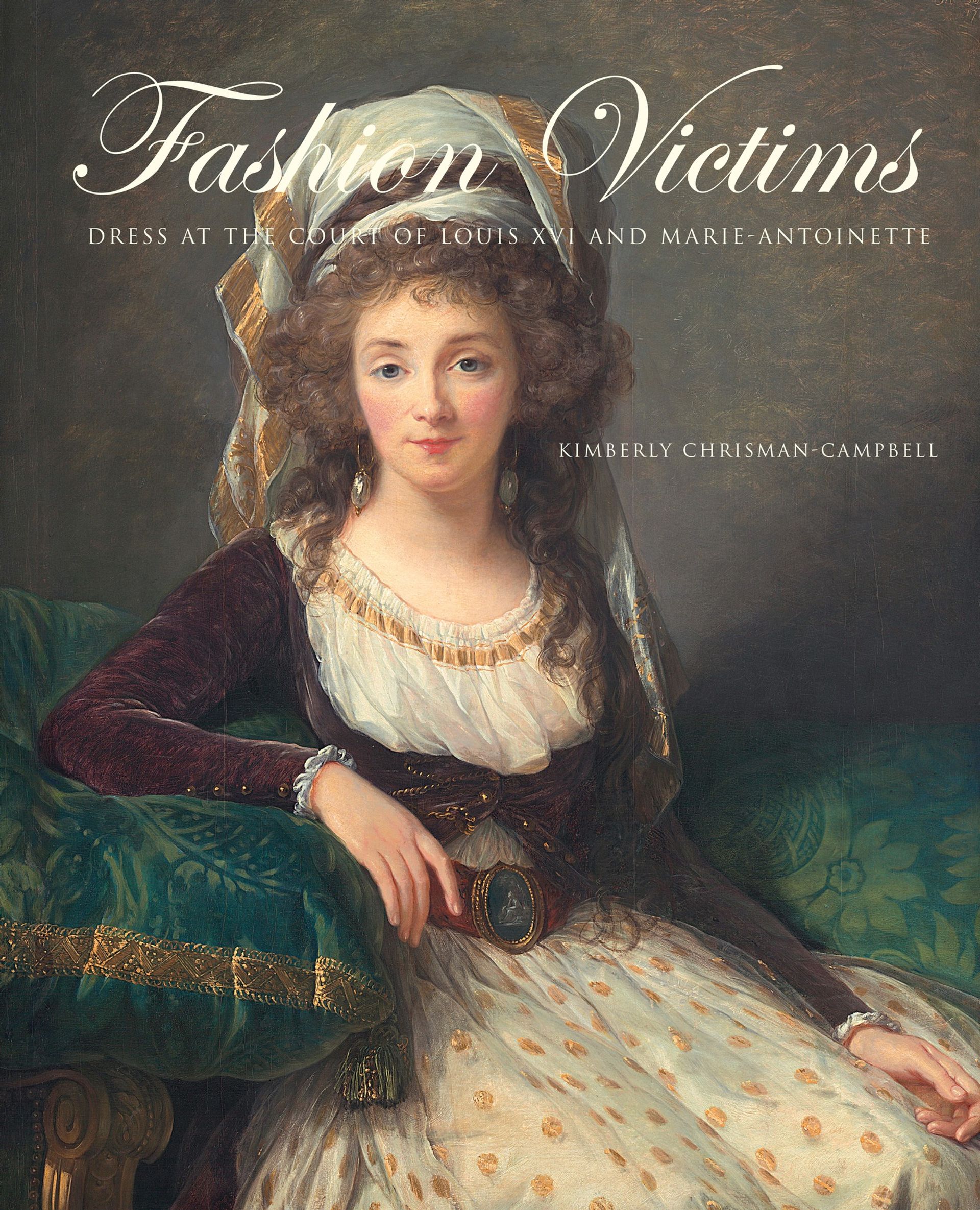

Anyone interested in social and political history, in art and in dress, will learn much from this book. It is lively and well written, with the high-quality design and attention to detail of Yale University Press; the illustrations, including paintings, fashion plates, extant garments and some beautiful textiles, are sumptuous.

Aileen Ribeiro is a professor emerita of the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, where she was head of the history of dress department from 1975 to 2009. The author of many books, her most recent is Facing Beauty: Painted Women and Cosmetic Art (2011). She is currently working on a book about the relationships between art and fashion

Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell

Yale University Press, 352pp, £35 (hb)