When the Getty Center opened in 1997, reviews of the $1bn project, designed by Richard Meier, had a common refrain: the giant complex, perched high above the 405 freeway and requiring a tram to deliver art pilgrims to the new mecca, was aloof from the community it had been built to serve. Martin Filler in the New York Review of Books dubbed it “the Big Rock Candy Mountain”, referring ironically to its almost mystical and dreamlike promise. Using the language of utopia, CNN called it a “grand temple on a hilltop”—the salvation of a culturally backward people, some seemed to think.

Bedtime stories about Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim and the “Bilbao effect”—civic transformation brought about by the construction of a wildly popular building—increased pressure to create an international landmark. But like many dreams of cultural institution-building, the reality was complicated, and the Getty has had a particularly strenuous uphill battle.

The Getty Trust, formed out of a bequest by the oil tycoon J. Paul Getty, who died in 1976, has been composed of various elements. Currently, it consists of the Getty Conservation Institute, Getty Research Institute, Getty Foundation (its grant-giving body) and J. Paul Getty Museum, with locations in the Santa Monica Mountains (Getty Center) and the Pacific Palisades (Getty Villa).

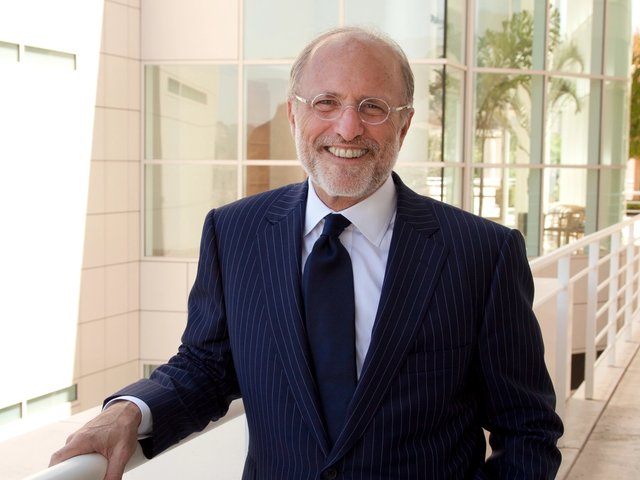

“When the Getty Trust was established, our trustees decided that its foreseen international reach could richly enhance the cultural and intellectual life of greater Los Angeles,” says James Cuno, the trust’s chief executive, who formerly led the Art Institute of Chicago.

Accusations of exclusivity and isolationism, mostly unfair, dogged the Getty Center in its early years. Even while celebrating its opening, the Washington Post said that grumbling never ceased “about the ‘elitist’ decision to build above the city”. There was much sniping at the leadership from within and without. Attacking the administration for its strategic priorities (early on, a preference for education at the expense of the museum; more recently, favouring the museum above education) started to seem like a favourite pastime in Los Angeles.

Now, nearly 20 years after its opening, the Getty is experiencing a renaissance under Cuno, who took over in 2011 after the sudden death of his predecessor, James Wood. Leveraging its enormous capacity and resources, and world-famous expertise, the Getty is realising its early promise of becoming an apostle for culture in the City of Angels.

Its most prominent local project has been Pacific Standard Time (PST), launched in 2011 to “tell the story of the birth of the Los Angeles art scene and how it became a major new force in the art world”, as explained on the Getty’s website. Involving more than 60 other Southern California organisations, it attracted worldwide attention. Deborah Marrow, the director of the Getty Foundation, and the driving force behind the initiative, says: “PST was a dramatic example of what can be accomplished with that kind of collaboration. It really is a tribute to the dozens of organisations that participated—this kind of working together is unprecedented among cultural organisations.” The next stage, beginning in 2017, is PST:LA/LA; it focuses on the relationship between Los Angeles and Latin American and Latino art.

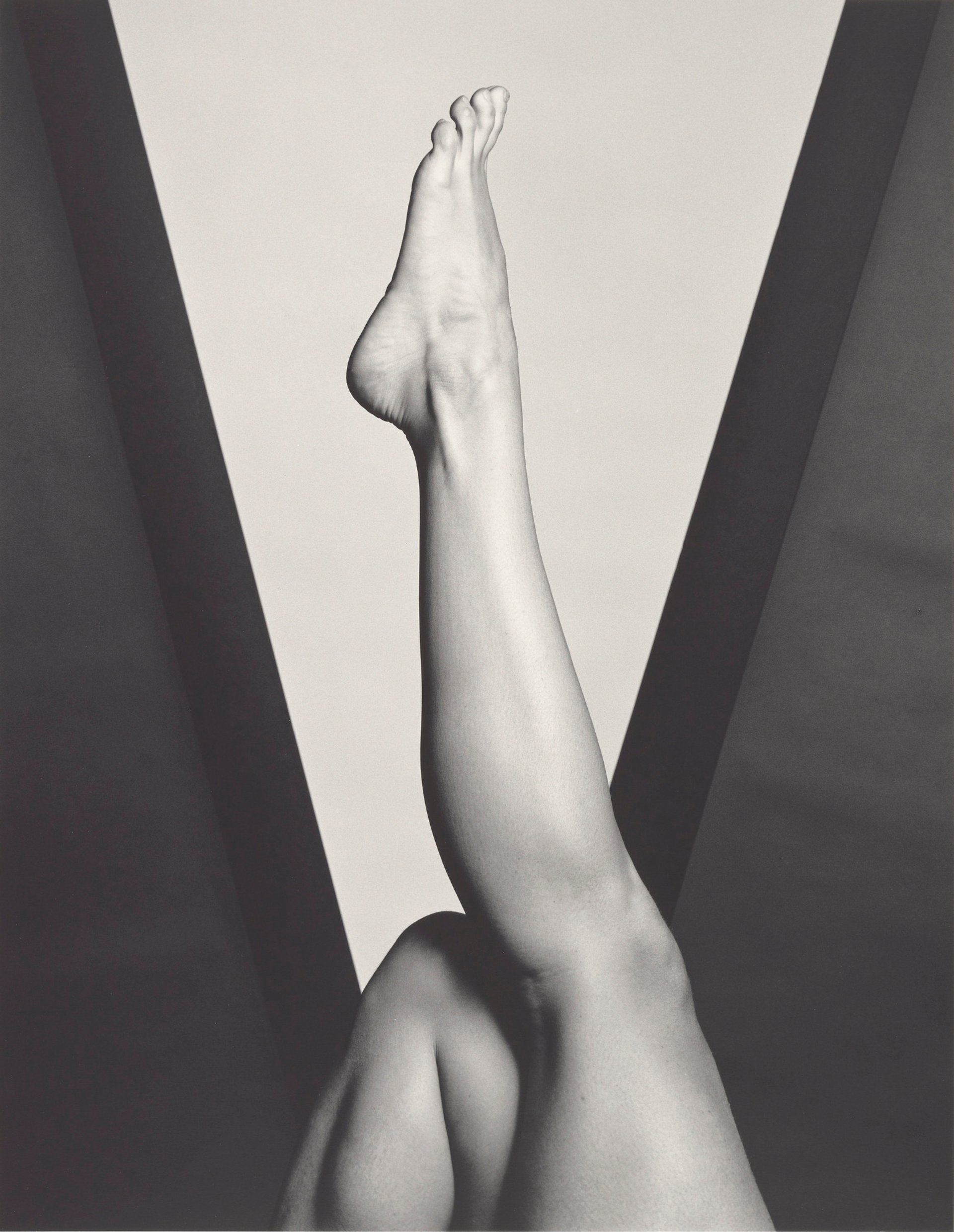

Also in 2011, the Getty Museum joined with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) to buy the collections and archive of Robert Mapplethorpe, the New York photographer who died from Aids in 1989. Beginning next year, the Getty and Lacma will jointly present exhibitions of highlights of the Mapplethorpe acquisition.

While the Getty Museum is the most visible organisation in the Getty Trust (according to TripAdvisor, it is the fourth most-loved museum in the world), the others have been quietly raising their profiles. In February, the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), together with the city of Los Angeles, launched HistoricPlacesLA.org, the most comprehensive open database of regional historical mapping, contextual data and research. The Getty Foundation provided a $2.5m grant, matched by the city authorities.

“Usually, when such surveys are done, they get put on the shelf and no one knows where they are,” Tim Whalen, the director of the GCI, says, “but transparency, accessibility and sharing of knowledge are key values of ours.”

The Getty Research Institute (GRI) has been seen as the outlier in the Getty Trust family. Focusing on scholarship and resembling a university department, the organisation rejected the culture of the “art world” and its obsession with the latest multimillion-dollar purchases, in favour of historical, archival research. The result was isolation within the Getty Trust, which was itself accused of being remote.

The appointment in 2007 of the German art historian Thomas Gaehtgens, who has an intense interest in cultural ephemera, changed this. The widening of “art” to include posters, pamphlets, archives, consumer objects and historical artefacts helped bridge the divide with the other Getty institutions. The GRI is now one of the leading engines of creative experimentation in the US, recently presenting new research in a powerful exhibition about the iconography and visual design of the First World War. This was followed by A Kingdom of Images: French Prints in the Age of Louis XIV, 1660-1715. In autumn 2015, the GRI dives into the topic of food illustration.

“Research is done to understand objects, history and art in context,” Gaehtgens says. “Storytelling is about communicating that research. The GRI brings together this entire process.”

The Getty Trust’s collaborative spirit has made it the go-to place for smaller organisations, such as the Architecture and Design (A+D) Museum, the El Segundo Museum of Art (ESMoA) and the Wende Museum, of which I am the executive director, to obtain expert advice and support. The Getty Foundation has supported multicultural internship grants for more than 150 local organisations, including ours; the GCI’s Devi Ormond has provided conservation planning for the Wende’s collections, as well as for other regional institutions. The Wende recently kicked off a partnership with the GRI to present a show around both institutions’ collections of art, ephemera and archives from Communist-era Hungary.

The Getty has also embarked on the Open Content Program, which will digitise and make available the collective resources of the various institutions, including thousands of freely shareable images. The Getty Research Portal is the dominant database for digitised information relating to art.

“Almost every art historian uses it—I am very proud of that,” Gaehtgens says. “Our offices are beautiful cloisters. They are monk cells that allow the space to develop ideas, but it is also essential to open up and share what we’re doing with the outside world.”

The Getty Trust, like the city of Los Angeles itself, is relatively new, but in its short history it has challenged accusations of elitism and aloofness to become a paragon of co-operation, openness and cultural leadership. The Big Rock Candy Mountain has achieved renown and respect, and while the temple on the hilltop continues to look over Los Angeles, the organisation has once and for all come down from the hill.

• Click here for a full report on the first 30 years of the GCI.