It is no real secret that Vincent van Gogh was drawn to nature and that it shaped his work. In his letters, van Gogh writes of hunting down beetles and birds’ nests as a child and identifying insects by their Latin names. He also painted those creatures, swamps, farmland, wheat fields and the natural ambience of everywhere he went.

The evidence is on the walls, in almost 50 works at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, in the exhibition Van Gogh and Nature.

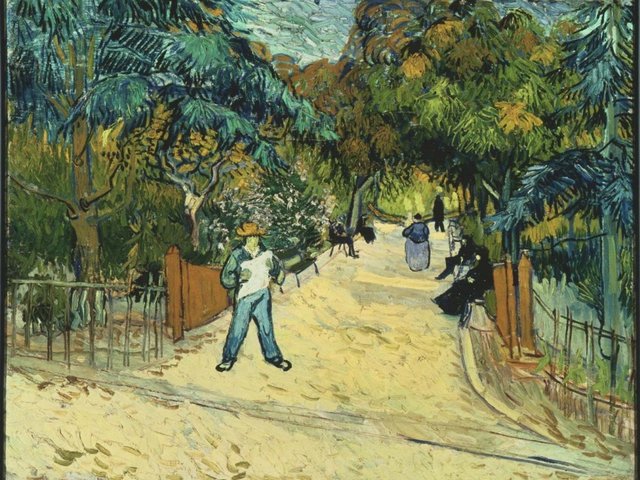

Yet the question arises: what is nature? The show’s curator Richard Kendall and his team define the term as broadly as van Gogh did. Nature is the natural world, wherever van Gogh found it, whether it was in the grey expanses of rural Holland, in untended vegetation in a Parisian park, in a vase of flowers or in the garden of the asylum in St. Remy, where the artist was committed the year before he died.

This makes for quite a bouquet at the Clark. And in van Gogh’s studies, where the artist’s life and work have been analyzed in every possible way, it is a novel walk through a much-traveled itinerary.

Nature wasn’t just a subject for van Gogh, it was also an immersion, an inspiration. This is the man who wrote: “I have a terrible clarity of mind at times, when nature is so lovely these days, and then I’m no longer aware of myself and the painting comes to me as if in a dream.”

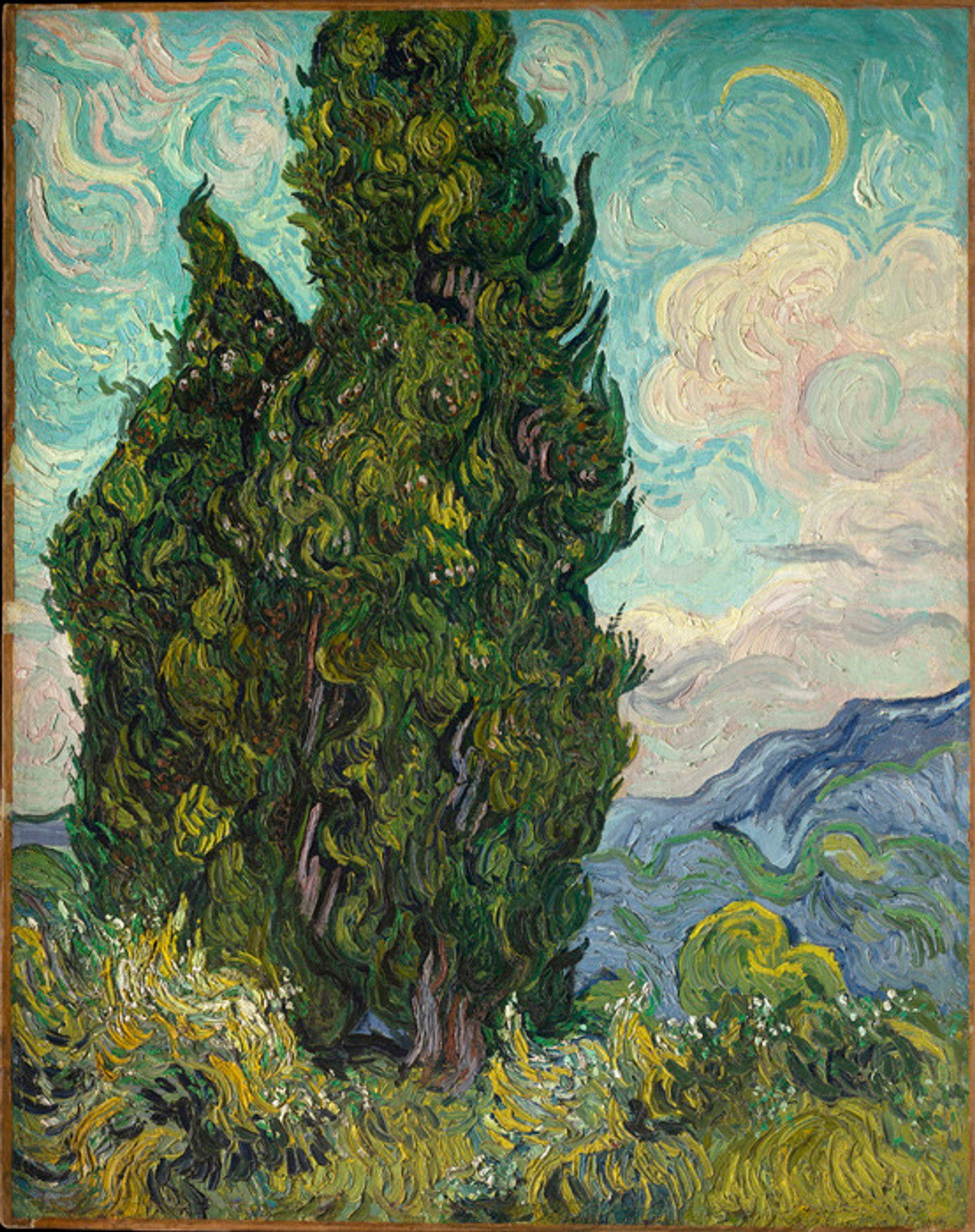

In the Clark exhibition’s van Gogh chronology, we see soberly-observed drawings of the swamps of Nuenen, where van Gogh’s pastor father served a small congregation. Leafless gesturing trees that anticipate the tremulous cypresses he painted in Provence years later foreground what would otherwise be a bleak, unimpeded grey horizon. Figures in these pictures are rooted in nature and trapped there. Van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters (1885) drives the point home. The dirt-poor souls in these works are painted as part of the land where they live, whether they are in the earthen palette of the potatoes they dig up, or going underground to the coal mines. These were van Gogh’s years of religious faith and social engagement. The nature he saw was as grey-brown as a worn bible cover.

From van Gogh’s Paris years, when he lived with his art dealer brother, Theo (who supported van Gogh financially) we see Undergrowth (1887), the trunk of a tree that van Gogh isolates as a place unto itself. Was he the urban Courbet? It is an improbable shrine, but van Gogh has made untended vegetation something of a shrine nonetheless. His scenes of jumbled Montmartre hillsides, where city-dwellers tended allotment gardens, are hardly stirring landscape paintings, yet they are uneasy meditations on maneuvers by ordinary folk to hold back the tide of urban expansion.

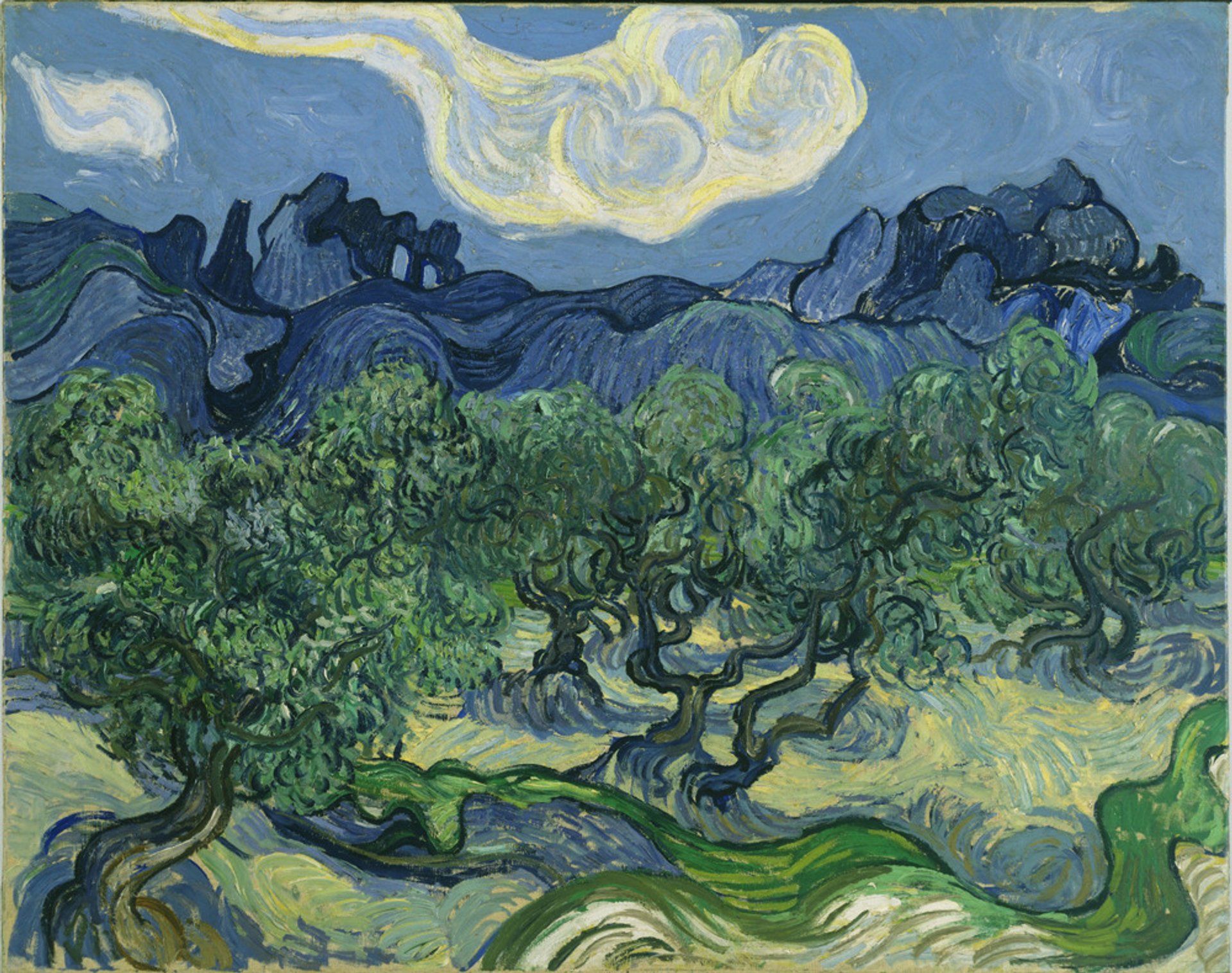

As van Gogh decamped from Paris for Arles in the south of France in 1888, his faith wavered, but his surroundings offered endless subjects. The natural world met the artist’s reveries, as van Gogh assimilated the tradition of landscape painting from Jacob van Ruisdael to Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot to Charles-François Daubigny, and deployed the colors and compositions of Japan, which he had seen in Paris.

“If we study Japanese art,” van Gogh wrote, “then we see a man, undoubtedly wise and a philosopher and intelligent, who spends his time—on what?—studying the distance from the earth to the moon?—no; studying Bismarck’s politics?—no, he studies a single blade of grass. But this blade of grass leads him to draw all the plants—then the seasons, the broad features of landscapes, finally animals, and then the human figure. He spends his life like that, and life is too short to do everything. Just think of that; isn’t it almost a new religion that these Japanese teach us, who are so simple and live in nature as if they themselves were flowers?”

Yet beware, cautions the curator Richard Kendall: “He was rarely guided by simple logic, and his practical approach to this transformation was characteristically idiosyncratic, if not actually perverse.”

Visitors to the Clark will reach that conclusion soon enough. The exhibition follows van Gogh through the Alpilles, the hills outside St. Remy that he painted green and blue, and to back north to Auvers, where he put wheat fields into perpetual motion. His pictures, like his letters, shift from witnessing to imagining.

Like it or not, the exhibition is also a road map for van Gogh’s psychological journey. Yet the artist’s spiritual struggles are refracted through these views of nature, and not foregrounded as they are in the well-known self-portraits. For a literal reminder of the artist’s deeper crisis—literal, that is, by van Gogh standards—there is a 1962 etching of van Gogh’s Portrait of Doctor Gachet (1890), the wobbly image of the physician who was treating him.

The Clark reached deep into its own holdings for the show and found works by other artists who shaped van Gogh’s approach to landscape or who broadened his palette, with some surprises. The improbably stark Cows at a Watering Hole by Daubigny, a drawing in red chalk from 1863, helps set the mood for the transformative powers of color. Prints by Utagawa Hiroshige introduce tones that van Gogh would revisit in his own vision of the sun and vegetation around Arles. A pastel of Jean-Francois Millet’s The Sower from 1865 is embellished in van Gogh’s larger painting of the same solitary figure with a dappled blue-gray field and an orange sunset.

Nature, so broadly conceived, gives us the darkly tactile van Gogh and the artist at his hallucinatory extreme. The Clark’s expansive hills and woods in Williamstown offer an environment to mull over it and return to the galleries for further germination.

David D’Arcy is a correspondent for The Art Newspaper.

Van Gogh and Nature, The Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, until 13 September